Registered with the Registrar of Newspapers for India under R.N.I 53640/91

Vol. XXV No. 10, September 1-15, 2015

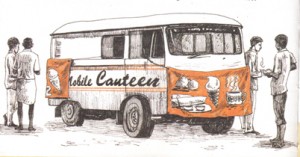

Saved by the mobile canteen

As Queen Mary’s College celebrates its Centenary, we came across this recollection of the College and its hostel food in the 1940s. This is in a memoir titled Tiffin* (a recollection of her life as well as recipes of the tiffin items she had enjoyed) by Rukmini Srinivas. These excerpts are published with her permission.

(Continued from last fortnight)

When, during my first days, I found the food in the hostel unappetising and often made only a pretence of eating it, Juliet, a pragmatic person, advised, “Don’t sit and moan; do something to improve matters.” She suggested that I buy a tiffin carrier, so I could get snacks or food from the mobile canteen which parked right opposite the college every evening between four and nine o’clock. In a few days, I became an ardent devotee of the red and blue van that provided me with my daily tiffin favourites.

Rukmini Srinivas (dark saree) and her colleagues in Queen

Mary’s College.

The mobile canteen arrived with great fanfare on the Beach Road, playing loud and cheerful Tamil cinema music. Cloth banners displaying the mouth-watering fare fluttered from the front and back of the van, tempting the beach crowd with crisp brown bondas, golden dosai, bowls of fruit salad and ice cream, and rich brown coffee.

By four o’clock every evening, my thoughts and senses wandered to the aromatic, hot and crunchy Mangalore bondas and hot coffee that were served from the van window. My dorm mates and I preferred to enjoy eating the snacks leisurely in our rooms.

Buying food from outside was not new for the hostelites, and this need was acknowledged and accepted by the hostel tutors as long as no outsiders entered the hostel rooms. The hostel rules were very clear, especially ones that pertained to banning of entry of males to the first and second floors, the residential section of the hostel.

The ferrying of food from the mobile canteen to the hostel fell to the lot of the ‘chhokras’, the young ‘ball picker’ lads in the tennis courts of the college. By four o’clock every evening, half a dozen of them would hang about the staircase, knowing well that their services would be needed.

This Pavlovian conditioning was not peculiar to me alone. I was not the only famished slave of the mobile canteen. Soon, a group of my dorm mates assembled on the wide verandah outside our rooms facing the front garden of the college, each with her favourite snack for the evening and ready for an impromptu party. Masala dosai, Mangalore bonda, medu vadai, masala rice, and packets of coconut barfi, peanut brittle and semolina fudge would be spread out before us.

I do not know how much the others spent each evening on their tiffin from the mobile canteen. I remember, we were six of us in the group who shared our snacks on most evenings. And there was quite a variety and plenty to go round. My guess is, each of us would have spent about five rupees. Three of our groupmates were Tamil movie buffs, who divided their personal expenses between film tickets on weekends and the mobile canteen on some weekdays. As for me, I felt no guilt in spending on tiffin since I rarely went to the movies.

I graduated with a master’s degree in Human Geography from the University of Madras in 1952, and the same year I joined Queen Mary’s College as a junior faculty member. It was my good fortune that there was a vacancy in my own college, but the competition for that one vacancy was tough. I went with trepidation to the Madras Public Service Commission interview where fifteen other qualified aspirants had been invited. This was my first job interview. I was both nervous and anxious about the outcome of the interview. But my father’s advice in his letter to me was: “Just be younself. If one door closes, there will be others that open.”

The interviewing board consisted of an all-male committee of eight members, three of whom were geographers from other universities; the five others were administrators and government officials from Madras, as I learnt later. The five non-geographers set the tone for the interview, and when the oldest of them, the one with a shaggy walrus moustache and navy-blue jacket adorned with an impressive and colourful collection of medals, bellowed as I walked in, tripping over the carpet, “Come in, young lady, sit down, relax and tell us about yourself. We are not here to disembowel you…” I felt less intimidated. The remaining half hour in the company of these august men was spent in pleasant conversation. It did not matter that not much of it had to do with what I thought I was there for, but I left them feeling good. I dit not have to prove myself.

I was delighted when ten days later I received a letter of appointment, and my former teachers were happy to welcome me as a colleague. My teaching duties were heavy, as I taught two courses to students in the first and second year intermediate classes, and one course for each of the three-year Bachelor of Science and Bachelor of Arts students.

Within a few weeks of joining the department, I was invited to fill a vacancy in the staff committee of the college dramatics association and the debating society – I had been an active student member of both societies, and this was a welcome diversion and therapeutic in many ways for me. My enjoyment of acting and playwriting started as a school student and continued through my college days.

When I wanted to unwind, I went home to Tanjore over the weekend. And my father, as always, would be awaiting my arrival with eager anticipation to listen to my stories of college life, prodding me for my observations and more details of the student community, my friends, the staff and college events.

Queen Mary’s College was established for the higher education of women, and though I found many of my fellow students meek and mild, the all-women teaching faculty was spirited and independent. I realised early on that here was an anomaly. In an otherwise conservative society such as I found in Madras, these women held liberal views, whether in social behaviour or politics, and that was refreshing. I enjoyed my three years as lecturer in Queen Mary’s.

While I thought of myself as an educated, independent woman, the stark reality was that I continued to depend financially on my father. I must add that the state pay scale was miserable, and my starting salary was less than hundred rupees per month, which was a pittance compared to my living expenses even as a student in the same institution.

I was allotted a room in the Beach House, one of the staff quarters on the college campus facing the Marina, and that was home to me till I resigned my lecturership in 1955 when I married Chamu.

(Concluded)