Registered with the Registrar of Newspapers for India under R.N.I 53640/91

Vol. XXV No. 15, November 16-30, 2015

Know your Fort better

by Sriram V.

One of the most striking aspects of St Mary’s in the Fort is the number of funerary monuments, commemorative plaques, intramural tombstones and statues that dot its interior. Going through each one of them is perhaps a chore best left to epigraphers and historians, but some of them do merit a second look. Before we go on to them, however, a word about the hidden altar of the church would be in order.

Today, as you stand facing the east, all you see is Willison’s depiction of The Last Supper dominating the altar wall. Thanks to its dark brown background, it gives the entire church a slightly gloomy feel. This was not always so, for behind the painting is a full length stained glass window that has inscribed above and below it the altar verse of St Mary’s – ‘If Ye Love Me Keep My Commandments.’ This is an extract from the Bible. There is no record as to when the painting was shifted to block the window but when it did, it cut off all light from the east. Then, probably in order to protect window and painting, the Archaeological Survey of India in 1950, with no doubt the best intentions, built a brick wall on the eastern front, thereby entombing the stained glass between the painting and the wall. That means this altar window, or the hidden true altar, can be accessed only if The Last Supper is moved and the wall demolished!

Let us now look at those who, like the wall, are entombed within the church. At the foot of the space marked for the choir, pulpit and lectern, are two rows of rectangular slabs, below which lie some illustrious men. The first line begins with Sir George Ward, Governor of Madras for a brief while in 1860, dying of cholera within a few weeks of taking office. Next to him lies the Rt. Hon Vere Henry, Lord Hobart, also Governor of Madras and a victim of typhoid, his death happening in 1872. After his tomb is one that has inscribed on it a cross and the words ‘In Memoriam’. And this has a story to tell.

George Pigot was Governor of Madras twice, in the 18th Century. But even before that, he had proved his mettle, being a go-getter who played an important role in the defence of Madras during the French siege of 1758/59. He became Governor subsequently, indulged in all the malpractices that those in power then did and retired to England in 1763 with a fortune of Rs 40 lakhs. He purchased an Irish peerage, became Lord Pigot and would have settled down to a life of leisure had he not been called back as Governor of Madras in 1775. The Nawab had just then invaded and occupied Tanjore, egged on by Members in Council and several dubashes, all of whom wanted to lay their hands on the fertile Cauvery delta. The Company, however, frowned on it and Tanjore was restored to its rightful ruler but not before Pigot had fallen out with his Council on the matter of the correct procedure for restoration. He was arrested by his detractors and sent to St. Thomas’ Mount where he was kept in some sort of house arrest though he was free to move around there and also entertain. While there, he suddenly died, the circumstances of his death having never been established clearly. His body was brought hastily to St. Mary’s and buried in an unmarked grave, the location of which was forgotten. In 1875, when the space before the chancel was being dug to accommodate Lord Hobart, an unmarked coffin was found. The new Governor, the Duke of Buckingham and Chandos, decreed that this ought to be the last resting place of Pigot and had the slab now seen placed over the spot.

In the second row of intramural burials is the tomb of Sir Thomas Munro, Governor of Madras, who died of cholera at Gooty in what is now Andhra Pradesh in 1827. He was initially buried there and it was only in 1831 that his remains were shifted to St Mary’s. On a pillar close by is a portrait medallion in his memory. Munro was greatly loved and respected by the people of Madras, an affection that continued long enough for people such as Rajaji to speak in his praise. His equestrian statue stands on the Island, not far from St Mary’s.

That would complete the roster of Governors of Madras buried here, all except the first among them to merit this honour – Francis Hastings, who held that office between 1720 and 1721. He is interred just outside the church proper, his stone lying beneath the tower’s arch that leads to the walled garden. Buried within the church are also some other leading lights – Sir John Doveton, known chiefly for his interest in Sanskrit and his being guardian to the sons of Tippu Sultan while they were held hostage by the British, Sir Archibald Campbell, Commander-in-Chief of the Madras Army in the 1820s, and Sir Samuel Hood, C-in-C of the Royal Navy.

A memorial in St Marys |

Jane Amelia Russell |

Schwartz Monument |

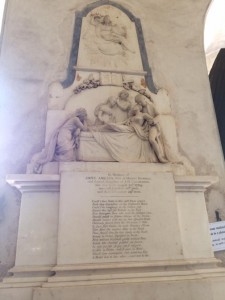

On the walls of the Church are several commemorative plaques, monuments and medallions. Most of them are in marble and executed by famed 18th/19th Century sculptors in England, such as John Flaxman, John Bacon (senior and junior), G. Clarke, Charles Peart, John Ternouth and Mathew Noble. Some of the striking ones in the church are the memorials to the Rev. C.F. Schwartz (by Bacon Jr), the Rev. C.W. Gericke (by Flaxman), Josiah Webbe (by Flaxman), and Geoffrey Moor house (by Peart). Two lifesize statues, at diametric ends of the church, are those of H H Pepper (by Clarke) and Thomas Conway, “the soldier’s friend” (Ternouth). Both Conway and Moorhouse were ardent Freemasons and among the founding fathers of the Lodge of Perfect Unanimity (PU) in 1789. The PU continues to function in Madras.

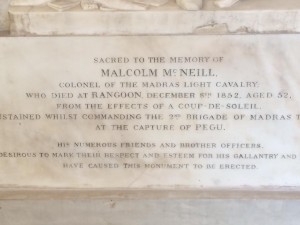

Looking around the Church, you realise the high rate of mortality that existed in India and the diverse reasons for it as well. Thus, while the Rev. Gericke was killed by a ‘fright brought about by monkeys’, at Rayacottah Fort in Salem District, Brigadier Malcolm McNeill died of a ‘coup-de-soleil’ (sunstroke) while serving in Pegu, in Burma.

Among the plethora of plaques is one commemorating Julian James Cotton, ics who died in 1927. It is rather appropriate that he has been honoured this way, for he is chiefly remembered today for his painstaking work – List of Inscriptions on Tombs or Monuments in Madras, first published in 1905. Also remembered is the supposed builder of St. Mary’s, Edward Fowle, Engineer and Gunner, Fort St. George. Though he died in 1685, it was only in 1906 that a brass plaque was unveiled in his memory here. This is set into the first of the six pillars that support the roof of the Church, counting them from the entrance. Facing it, on the western wall is a massive obelisk, which reminds the visitor of the Hynmer and Yale Monument in the Law College compound. This commemorates Lady Hobart (wife of a Governor in the 1700s) and her son.

In the days when St. Mary’s was a garrison church, its pillars were topped by the colours and flags of the various regiments stationed in Madras. Today these have all been removed to the Fort Museum where they remain on display.

If you can manage to tear yourself away from the Church, do go out through the southern entrance to the enchanting walled garden. Sit on one of its welcoming benches and look at the walkway that runs along it, parallel to the Church, connecting Charles Street and St. Thomas Street. This is accessed at both ends by wrought iron archways that are securely locked. Could this have been Church Lane or Church Row where one of the Fort’s most sensational romances was played out? More on that in the next episode.