Registered with the Registrar of Newspapers for India under R.N.I 53640/91

Vol. XXVI No. 05, June 16-30, 2016

Was India his inspiration?

(by Kumaran Sathasivam)

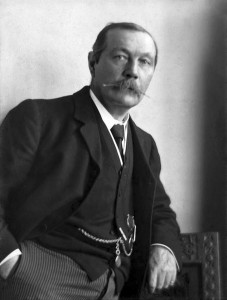

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle

Round his brow (Dr. Grimesby Roylott) had a peculiar yellow band, with brownish speckles, which seemed to be bound tightly around his head. As we entered he made neither sound nor motion.

“The band! the speckled band!” whispered Holmes.

I took a step forward. In an instant his strange headgear began to move, and there reared itself from among his hair the squat diamond-shaped head and puffed neck of a loathsome serpent.

Thus do things come to a head in Arthur Conan Doyle’s well known short story, ‘The Adventure of the Speckled Band’, with the villain, Dr. Roylott, falling into his own trap.

Roylott, a widower, is given to violent rages, and returns to England from India after serving a jail sentence for killing his butler in one of his bouts of temper. He lives with his two step-daughters in a run-down manor, all that remains of the vast estates of an aristocratic family. Roylott lives on an annuity arranged for by his late wife. The two step-daughters are entitled to claim a third of this annuity each upon marriage. Roylott has a motive, therefore, to prevent the marriage of either step-daughter. He maintains exotic pets from India, including a cheetah and a ‘baboon’. When one step-daughter gets engaged to be married, he introduces a venomous snake into her room when she is asleep – the snake bites her, killing her swiftly. Roylott has trained the snake to return to him when he whistles for it. The marks of the teeth are not detected by the coroner, and the cause of the step-daughter’s death remains an unsolved mystery.

Two years later, when the second step-daughter gets engaged, Roylott attempts to kill her in the same manner. But Sherlock Holmes saves the day, and the serpent bites its ‘master’.

‘The Adventure of the Speckled Band’ is only one among several stories by Arthur Conan Doyle that have references to India. Some of the Indian connections are trivial, whereas others are critical. For instance, in ‘The Adventure of the Three Students’, one of the students is Daulat Ras, a young Indian. And in ‘The Five Orange Pips’, Colonel Elias Openshaw, settled in West Sussex, receives a letter postmarked Pondicherry. Later in the story, Sherlock Holmes checks the sailing records of all the vessels that touched Pondicherry during January and February 1883. (‘There were thirty-six ships of fair tonnage which were reported there during those months.’) A third example is ‘The Boscombe Valley Mystery’, in which Holmes deduces that the murderer, inter alia, smokes Indian cigars.

Why does India feature in so many of these stories by Doyle, set entirely in Britain? The fact is that by the time that Doyle began writing his stories, India was the ‘jewel in the crown’ and had a deep relationship with Britain. In the words of James Morris, “If much of the Empire was a blank in British minds, India meant something to everybody, from the Queen herself with her Hindu menservants to the humblest family whose ne’er-do-well brother, long before, had sailed away to lose himself in the barracks of Cawnpore. India was the brightest gem, the Raj, part of the order of things: to a people of the drizzly north, the possession of such a country was like some marvel in the house, a caged phoenix perhaps, or the portrait of some fabulously endowed if distant relative. India appealed to the British love of pageantry and fairy-tale, and to most people the destinies of the two countries seemed not merely intertwined, but indissoluble.”

Given this fascination with India, Doyle, as we may expect, was far from alone in bringing India into his works. Indeed, the branch of English literature dealing with or mentioning India is vast. Back in 1973, one author listed 2272 fictional works in this genre – many more have been published since then. Most of these works are about the British community in India.

The subset of authors who have introduced Indian wildlife into their fiction is relatively small. Arthur Conan Doyle, in bringing an Indian snake, cheetah and baboon into The Adventure of the Speckled Band, which was published in 1892, was one of the earliest members of this select group.

Rudyard Kipling joined the club soon after, with the publication of Jungle Book and Second Jungle Book in 1894 and 1895. Subsequent works of the genre include Mrs. Packletide’s Tiger, by H.H. Munro (‘Saki’), and Jungle Picture, by Norah Burke. You could also claim that George Orwell’s Shooting an Elephant, set in Burma, belongs to this category of literature, but there is a possibility that this is an autobiographical essay and not fiction.

It has been surmised that Doyle was inspired to write ‘Speckled Band’ after reading an article titled ‘Called on by a Boa Constrictor: A West African Adventure’, which appeared in the Victorian Cassell’s Saturday Journal. This article is reported to be an account by a captain of how a large snake descended into his cabin in the night through a ventilator. The captain raised the alarm by ringing a bell. But you could offer other suggestions for Doyle’s source.

Doyle could have obtained information about Indian wildlife from the natural history books available in his time – books such as those by T.C. Jerdon (The Birds of India, The Mammals of India), Albert Günther (The Reptiles of British India), Robert Sterndale (The Natural History of the Mammalia of India and Ceylon) and Francis Day (The Fishes of India, in the Fauna of British India series). Countless books on shikar had also been published. Another potential source was the technical journals that had been or were being published: The Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal, The Madras Journal of Literature and Science, The Calcutta Journal of Natural History and, significantly, The Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society (JBNHS), the first volume of which appeared in 1886, just around the time that Doyle says his “brain quickened” and his “imagination and range of expression were greatly improved”.

An examination of the contents of the JBNHS volumes published between 1886 and 1892 (the year of publication of ‘Speckled Band’) allows you to draw up a list of articles on the basis of which it could be argued that these too could have inspired Doyle. This list is impressive: No fewer than 91 articles published during this period in the JBNHS contain the word ‘snake’. Eleven of these articles have ‘snake’ in the title. Among them are H.M. Phipson’s The Poisonous Snakes of the Bombay Presidency (1887, volume 2(4)), Ghore Pore’s Can Snakes Hear? (1888, volume 3(1)) and W.F. Sinclair’s How a Snake Climbs (1889, volume 4(4)). It should be recalled that in Doyle’s story, the swamp adder (1) is highly venomous, (2) climbs up and down a bell pull, and (3) has been trained to respond to a whistle. The coincidence, if that is what it is, is remarkable!

It could be argued that the JBNHS does not mention ‘swamp adders’ and that Pore’s article does not claim that snakes can hear. But these articles, if Doyle read them, probably only served to kindle his interest. Doyle’s imagination was fertile, as seen from his numerous stories, and he was not one to hesitate to invoke poetic license.

He writes in his autobiography, “Sometimes I have got upon dangerous ground where I have taken risks through my own want of knowledge of the correct atmosphere’. He goes on to add, ‘However, I have never been nervous about details, and one must be masterful sometimes…. On the other hand, there are cases where accuracy is essential.” Thus it is an intriguing idea that ‘Speckled Band’ is the result of Doyle having browsed through a set of JBNHS volumes, after which he exercised his literary skills, throwing in various imaginary details for dramatic effect.

Going through the body of Doyle’s works (Conan’s canon, as it were), one finds other tales in which there is an important natural history element. And when these are compared with the contents of the JBNHS volumes of the corresponding periods, the notion grows stronger that Doyle had access to the journal and drew inspiration from it.

Consider first ‘The Brazilian Cat’, a non-Holmes story, from Doyle’s Tales of Terror and Mystery. In this story, published in 1922, a man named Everard King has brought a number of creatures from Brazil to England, where he attempts to rear them. The pride of his collection is a ‘monstrous cat’. This is ‘a huge creature, as large as a tiger, but as black and sleek as ebony’. King explains, ‘Some people call it a black puma, but really it is not a puma at all. That fellow is nearly eleven feet from tail to tip’.

It happens that no fewer than three articles on black tigers appeared in the JBNHS up to 1922. The first of these articles was published in 1889, the other two in 1914. Further, in 1918, R.G. Burton wrote an article titled ‘Panthers’ in which there is a section on melanism and black tigers are mentioned more than once. Was this a coincidence again? If yes, it is all uncanny! On the other hand, if it is true that Doyle did glance through the JBNHS occasionally, it is perfectly acceptable that he should be fascinated by the idea of black tigers. His imagination would have conjured up the tale, and his story-telling skills would have introduced changes (India becomes Brazil, black tigers become ‘Brazilian cats’) for sheer exoticness.

Consider then the ‘Adventure of the Devil’s Foot’ (1917). A poison named Radix pedis diaboli (‘devil’s foot root’) is used in this tale. This poison has ‘not yet found its way either into the pharmacopoeia or into the literature of toxicology. The root is shaped like a foot, half human, half goatlike; hence the fanciful name given by a botanical missionary. It is used as an ordeal poison by the medicine-men in certain districts of West Africa and is kept as a secret among them’.

No deep search is needed to identify a possible source of inspiration – K.R. Kirtikar’s 20-part ‘Poisonous Plants of Bombay’ (1892-1903) is immediately obvious. And if we wish to go further and identify a particular plant that could have given rise to the idea of Radix pes diaboli, we need not look further than Volume 1 of the JBNHS. Kirtikar’s Note on the Gloriosa superba appears in the fourth issue of this volume. Kirtikar mentions reports about the poisonous nature of the roots of Gloriosa superba in the early article.

In the fourth part of his series, he describes the powerful emetic and purgative effects of the plant. He also describes the bulb of the plant (‘bilobed; vertical portion being half the shrivelled tuber of the current year; the horizontal portion being the new tuber…’). This is accompanied by an illustration of the said root. A bilobed root, with vertical and horizontal parts – the eyes of the imaginative writer could easily construe this as ‘half human, half goatlike’!

The evidence for Arthur Conan Doyle’s having been familiar with the JBNHS is entirely circumstantial, but it must be admitted that it is very convincing.

There is a postscript to this examination. For many of the initial years, the JBNHS carried annually the list of members of the Bombay Natural History Society.

In the lists of 1910, 1912, 1914 and 1915 appears the name of one James Doyle, from ‘Balaghat, C.P.’ Was this a relative of Arthur Conan Doyle’s? Did James Doyle send copies of the journal to a famous kinsman back in Britain? Considering the dates of James’ membership, this seems unlikely. The reverse may, however, well be true. Maybe Arthur Conan Doyle, familiar with the JBNHS, suggested to a family member in India that he enrol as a member of the society. – (Courtesy: Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society.)