Registered with the Registrar of Newspapers for India under R.N.I 53640/91

Vol. XXVII No. 16, December 1-15, 2017

Doubting Thomas

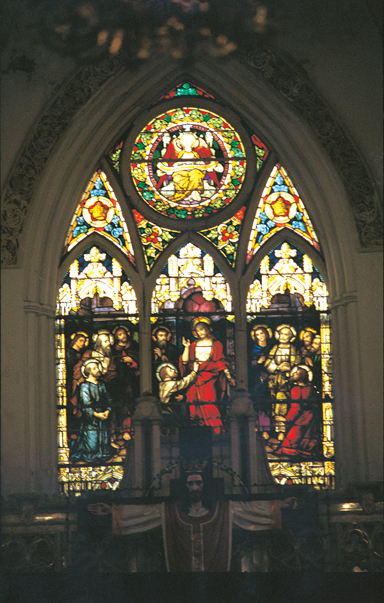

The beautiful stained glass backdrop to the altar in San Thomé Basilica tells the story of the Apostle of India, the Thomas who had doubted and found belief

December 21st is the traditional date of Thomas’s martyrdom. SIMEON MASCAREN HAS, who has spent time in the Portuguese Archives, reviews the story of the Thomas who became the Apostle of India.

In December 163 CE, a Christian merchant from Edessa in Upper Mesopotamia (Iraq today) arrived in the port of Supattinam (possibly Sadras). Hearing that the martyrdom of Thomas was to be commemorated on December 21st, the traditional date of Thomas’s martyrdom, the merchant went to partake in the celebration of the Eucharist at the saint’s grave in Mylapore. São Tomé, or San Thomé, would not be founded until the early 16th Century. On his return to Edessa by an overland route, his account of this experience stirred laity and clergy alike.

Two years later the same merchant set out for South India with a bold plan. He sailed to Mylapore where, in the dead of night, he removed the relics and conveyed them back to Edessa, arriving on July 3, 165 or 166 CE. In 1258, some of the relics were sent to the church of St. Thomas the Apostle in Abruzzo, Ortona, Italy.

So goes one of the legends of Thomas.

Nobody really knows whose relics lie beneath the São Tomé basilica, or even if any relics do. Faith and tradition are one thing, hard historical evidence quite another.

Although the oral tradition concerning Thomas’s Indian venture is strong, there is not a single written account in India. However, it is not wise to dismiss the oral traditions of the East as having no historical value. All the Syriac sources relating to the early Christians in India and the arrival of Thomas contain certain points that emerge as a common pattern: from the Chera country he moved to the Pandya realm, where he continued to preach the Gospel. He was killed by a dart shot by an Embran, or Brahman, or accidentally by a Govi who was out hunting. He was buried in the ‘Little Mount of Mylapore’. From there angels carried him to Uraha (Edessa).

None of the traditions report Thomas as having been martyred in Kerala. They all agree that this happened in the Pandyan country, the name of Mylapore occurring without exception.

On his return voyage from China, Marco Polo visited Mylapore in 1293 and stated confidently that “the Body of Messer St. Thomas, the Apostle lies in the province of Maabaar at a certain little town having no great population. Both Christians and Saracens also do hold the Saint in great reverence.” Franciscan priests ministered to a small Christian community in what became Luz. Later, Paulinus do San Bartolomeo (John Philip Wesdin) wrote that “All Christians of the East, Catholics and heretics like the Nestorians, Jacobites, Armenians, the Catholics of Bengal, Pegu, Siam, Ceylon, Malabar and Hindustan, come to make their devotions, and this alone is sufficient to confirm the ancient and universal tradition that St. Thomas died at Mylapore.” Paulinus was an Austrian Carmelite monk who worked as a missionary in South India between 1774 and 1789. Among his many publications is the first European grammar in Sanskrit (Sidharubam seu Grammatica Samscrdamica), published in Rome in 1790.

In the church of Nossa Senhora da Luz can be seen the Franciscan emblem: crossed arms over a crucifix. Over the lintel of the front door is the date 1516, suggesting that this is the year Roman (Western) Christianity came to the Coromandel Coast. In fact this is the year that the building we see was erected, a development over an earlier place of worship that was ministered by Franciscan priests. In 1291, the Franciscan John of Montecorvino entered India and remained at “the church of St Thomas”, where he baptised about 100 people into the Roman rite. Until this time, the Christians of Coromandel had followed the Eastern rite. The only conclusion that can be drawn is that there was a small but significant community of Eastern Rite Christians in the area, with trading links to Persia and the Levant. The situation of a Christian village on the outskirts of the ancient town of Mylapore is consistent with such a conclusion. Hence the local name for Nossa Senhora da Luz: Kaatu Kovil, or ‘Church in the forest’. These Eastern Rite Christians later subscribed to the Roman Rite under the influence of the Franciscan missionaries.

For six hundred years before the coming of the Portuguese to Malabar, there was a “perfect blank in the history of Christianity in Malabar,” according to K.C. Zachariah. On arrival in India, the Portuguese found the Thomas tradition commonly accepted everywhere in the South. A report dating from 1517 says that they were shown “a half-ruined church at Mailapur” and told that the apostle had been buried in a grave on the Gospel side of the altar: the right hand side as viewed by the congregation. On the opposite side, it was claimed, was the grave of a Christian ‘king’ named Thomas Mudaliar.

In 1523, the Portuguese, ever fanatical about correct documentation, ordered an investigation into the claim that the grave was that of the apostle Thomas*. Excavations were carried out on a weekend in July. After digging through three spans (about nine inches or 229 mm per span) of loose earth, four walls of a whitewashed brick grave were encountered. The bricks were about 15 ½ inches long, 8 inches wide and 5 inches thick. These measures correspond to those of bricks found at the first century Yavana (Greek or ‘foreigner’) site at Arikamedu near Pondicherry from the first century CE. Removal of these bricks walls revealed a layer of bricks and mortar two spans thick, then a further layer of loose earth, followed by a second layer of bricks that appeared to be the bottom of the grave. Breaking through the brick covering the excavators found three spans of earth, and under that a layer of extremely hard cement two spans thick. Beneath the cement they found two stone slabs bound together but with no inscription.

The following day work was resumed. The excavators reached the bottom of the brick lining. Three or four more spans of loose earth were removed. They were now at a depth of about 15 or 16 spans – roughly 12 feet or 3.6 metres. Here they found a bed of sand, and of lime which had crumbled into dust. Finally they came upon what might support the local claims: a skull, some ribs, then other bones, but far too few in number to make up a whole skeleton. There was also an earthenware jar with a capacity of an ‘almude’ – an obsolete Portuguese unit of measurement of about 16.54 litres in the Lisbon standard – filled with red earth, at the foot of the grave. From it stuck out a thigh bone, and inside was the blade of a ‘Malabaric’ lance or spear in the shape of an olive leaf. This lance tip was perfectly preserved and had in the shaft a piece of wood.

The orientation of the remains were north-south, an Islamic tradition. Christians were traditionally buried in an east-west position. Islam did not reach the Coromandel Coast until at least the 7th Century CE.

All the fragments of much-decayed bone were gathered into a chest, and, with a few other fragments that were unearthed during the excavation, placed in a Chinese chest with two silver locks.

It was common knowledge in the area that the site was attended by a Moor (Muslim), and that pilgrims of all faiths came from ‘all over India’ to pray at the site. The eminent Portuguese historian Joao de Barros (1496-1570) places the town of St. Thomas at 13o 32′ north of the equator, which would make the site correspond very closely with present-day Pulicat, not Mylapore.

Nevertheless, at the end of the lengthy inquiry that followed the excavation, it was concluded, on the basis of strong local tradition and the age of the bones, that the grave was indeed that of Thomas the Apostle. However, the burial could just as easily be that of an ancient Dravidian person of some note.

Although the ancient church of the Thomas Christians is of immense significance to Indians, the paucity of historical and archaeological evidence cannot offer certainty. Much of what is believed remains conjectural. However, history can offer probability in varying degrees. There is no clear written evidence that Thomas, the Apostle, preached in South India, the India of his era encompassing a vast geographical area. All scholars agree that Christianity existed in India from between the third and sixth centuries CE, the language of worship then being Syriac. It is entirely possible that the apostle Thomas came to India in the first century CE; there is as yet no evidence against this possibility.

As with most matters of faith and even history, due to a lack of convincing historical evidence, the question remains: who or what lies under sanctuary of the São Tomé basilica? Were the contents of that grave the remains of one of the many Levantine traders who settled along the Coromandel Coast 2000 years ago? Or a local megalithic burial? Is there nothing beneath the altar of the Santhome Basilica? We are unlikely to ever know. Faith and tradition have blended to the extent that nobody really cares to know the historical truth.

Based on the report of Diogo Fernandes in 1523.