Registered with the Registrar of Newspapers for India under R.N.I 53640/91

Vol. XXVII No. 24, April 1-15, 2018

Lost Landmarks of Chennai

SRIRAM V

The ghosts of Fort San Thomé

San Thomé High Road is a busy thoroughfare today with cars, buses and two-wheelers careening through it at all times. Hardly anyone in those vehicles is likely to pause to reflect that they are driving through what was once a fortress, complete with high walls, gates and bastions. And it had had its share of battles as well. In its time, it was twice the size of Fort St. George. Which is perhaps why the English disliked it intensely.

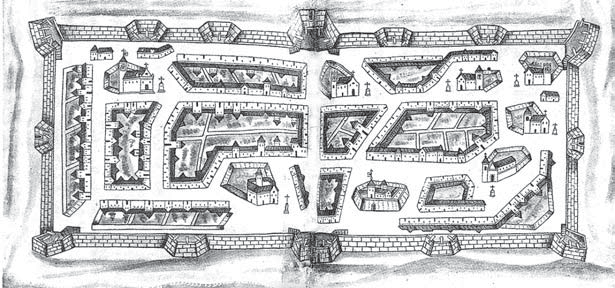

On paper, the Portuguese-built San Thomé fort has survived. Two maps of it are in existence, the first by Captain Pedro Barretto de Rezende, made in 1635, four years before Madras was founded. A map with no scale, it shows a rectangular fort with four gates, one at the middle point of each of the four sides. There were four churches within the Fort, apart from the Cathedral, and these were St. Paul’s, St. Dominic’s, St. Augustine’s and Our Lady. The last one has been tentatively identified as the present Rosary Church, built in 1635. Of the others there is no trace. Four churches of San Thomé, but outside the Fort walls, are also recorded. Of these, St Francis, which stood near the west gate, has vanished but still in existence and going strong are the Luz, St Lazarus and the Madre-de-Deus Churches. The Luz is well known and the other two are to the south of San Thomé. Lazarus Church is on a road named after it and as for Madre-de-Deus, it now goes by the name of Dhyana Ashrama, is much modernised and is on Mada Church Road, Mandaveli. The Mada Church is but a translation of Madre-de-Deus, Mother of God.

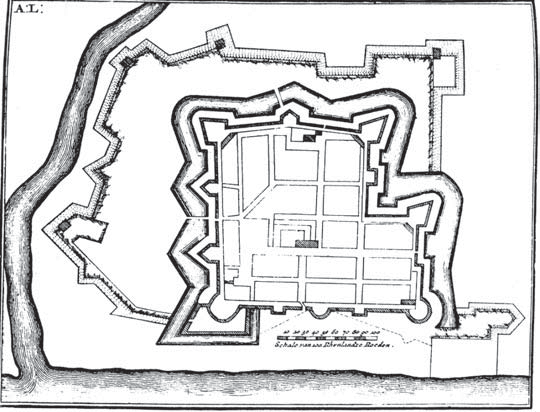

Francois Valentijn, a Dutch East Indiaman, made a second map, in 1674 and that is scaled. By then, the rectangle of de Rezende’s San Thomé had become irregular in shape. It had added a smaller rectangle to itself on the western side, thereby making inroads into Mylapore. The western boundary, complete with a new gate now stood on present day Kutchery Road, at the intersection of that thoroughfare with Bazaar and Devadi (Deorhi Sardar-ul-Mulk Dilawar Jung Bahadur) Streets. The whole enclosure now measured 825 by 780 yards (2475 by 2340 feet). The principal thoroughfare east to west was Rosary Church (which extends west as Kutchery) Road. This began at the west gate and went east beyond the cathedral to the seashore where there was a flagstaff. Another road ran north to south, which, had it survived, would have been parallel to and further west of the present San Thomé High Road, with gates at the northern and southern sides. A ditch ran around three sides of this Fort (the eastern side had the sea) and was most likely dry.

Life within this enclosure was not very peaceful and by the time the British had begun building Fort St George, many of San Thomé’s residents, particularly the women, were thinking of moving over to the new settlement. The heyday of San Thomé had been a hundred years earlier. In 1662, further chaos threatened when the Golconda forces, encouraged, aided and abetted by the Dutch in Pulicat, besieged San Thomé. The settlement capitulated and thereafter, for eleven years, the place was under the control of Golconda. A courthouse was built by the Golconda Sultanate and this kutchery lent its name to the road that ran alongside.

It is probably at this time that the flagstaff, referred to earlier, was erected at the eastern end of the Fort. This was a masonry pillar and over time came to be known as the Dutch flagstaff which was clearly erroneous, given that the Dutch never had control over San Thomé. It was the French that really succeeded in conquering the place. That was in 1672, when Admiral de la Haye anchored before San Thomé on July 10th and “marvelled at its fortifications”. The British in Fort St George were delighted with the prospect of the French laying waste the whole of San Thomé and Governor Langhorne sent a contingent of officers to welcome de la Haye and offer him all help. The French embarked on a two-pronged attack on San Thomé from July 13th. The ships opened fire from the east, while troops attacked from the southern side. Captain de Rebre was the hero of the day and by July 15th, San Thomé had surrendered. Its magazine was found to be full of gunpowder. There is still a Powder Mill Street in the vicinity that indicates where this was. The town was given over to the French troops for looting but the only place where anything of value was found was the Governor’s residence.

De la Haye had the western wall repaired and identified a place just outside it for the natives to set up a market. This place is still Bazaar Road. The west gate was named Porte Royale. The bastions were all given names – de la Haye, Caron, Marin, Portugais, St. Louis, de Rebre, Dauphin, l’Admiral, Bourbon, Francois, Major and San Peur.

But the French occupation of San Thomé lasted just two years. Admiral de la Haye tried his best to negotiate with the Sultan of Golconda for a permanent transfer but was not successful. The Dutch were too powerful for any progress. The Moors, the remnants of the old Golconda forces that had occupied San Thomé since 1662 had regrouped at Corumbat (probably Kodambakkam), and laid siege to the Fort. They were repulsed but not before a pagoda (temple), 400 paces from the western wall and which had been fortified by the French, was destroyed. Was this the original Kapaliswarar Temple?

By 1673 the Dutch and Golconda forces had joined up and renewed their attack on San Thomé. With the English at their prevaricating best, the French were isolated. De Rebre was killed and the blockade was so effective that the settlement and its garrison were reduced to starvation. Sea battles between the French and the Dutch were fought off Triplicane leading to the curious from Fort St. George and villages nearby to crowd the beaches. By September 1674, it was all over and de la Haye and his troops left. The English now began demanding that the Golconda troops demolish the San Thomé walls. This was begun in right earnest but given up sometime later. But in 1697, a contingent of the original Portuguese together, with some of the Mohammedan residents, tried to wrest power and rebuild the walls. The Governor of Goa sent his appointee to take over the administration. But by then the Moghuls were very much a local presence, via the Arcot troops. Sensing that this development could cause all kinds of trouble, they acted decisively. A contingent was sent and on January 8th that year it began to demolish all that was left of the San Thomé walls. The work was completed within a few days and for years afterwards, the debris of the Fort was used for construction in the neighbourhood. San Thomé fort vanished thereafter. In 1749, the area came under British control.

There are still some interesting vestiges. The eastern front of San Thomé is much higher than the seacoast and is accessed by a series of steps going down. This is not the case anywhere else in Madras. It probably indicates that much of San Thomé is standing on a masonry wall, perhaps the outworks of the original fort. The Dutch flagstaff was demolished sometime early in the 20th Century but made a comeback post 2004 as St. Thomas’ staff complete with a legend that the wooden pole that stands there was a staff of the Apostle and he had planted it to prevent any incursion of the sea beyond that point. That San Thomé was largely spared the horrors of the 2004 tsunami has only buttressed this legend.