Registered with the Registrar of Newspapers for India under R.N.I 53640/91

Vol. XXVIII No. 1, April 16-30, 2018

Lost Landmarks of Chennai

SRIRAM V

Kanpur’s butcher, Olde Madras’s hero

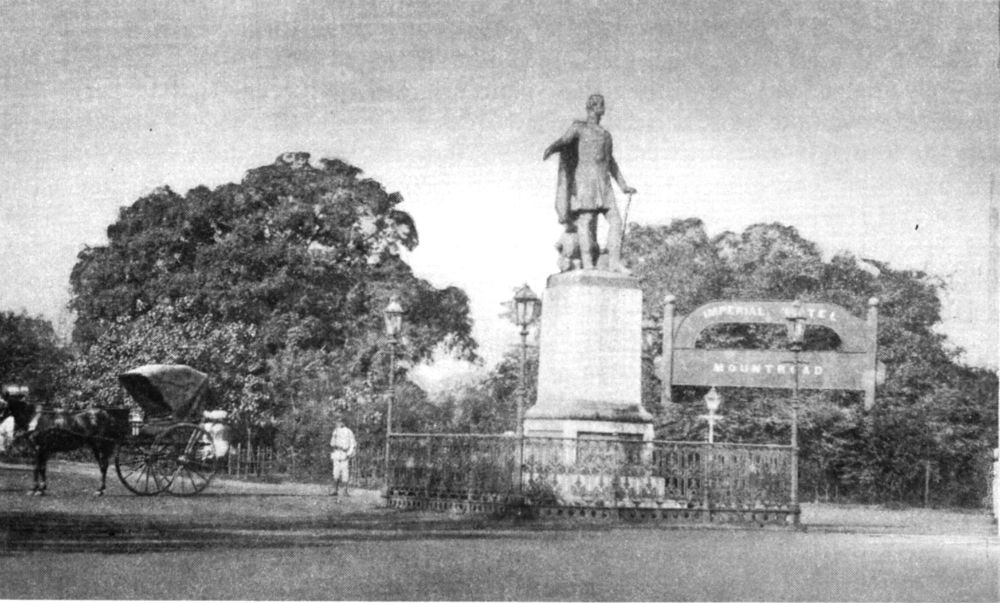

The Neill statue at what is now the Connemara (then the Imperial) Junction.

‘What we have to deal with is the statue and not even the statue as such. We seek to destroy the principle for which the statue stands…. Agitation for the removal of the statue is agitation for the removal of but a symptom of a grave disease. And while the removal of the statue will not cure the disease, it will alleviate the agony and point the way to reaching the disease itself.’

– Mahatma Gandhi , Young India

The Handbook of Madras Presidency, brought out by the well-known publishing house, John Murray (Firm) in 1892, has this to say about Colonel Neill’s statue:

“In driving along the Mount Road to the Cathedral, which is just 3 miles from the Fort, the statue of Colonel Neill is passed a little before reaching the second mile. It is close to the Club, and looks away from it. The hero is represented standing with his sheathed sword in his left hand, and his right pointing, as if giving a command. At the base is a fine alto-relievo of a battle, with Highlanders and guns, and at the back is, “Erected by public subscription, 1860.” On the other two sides are the names of the non-commissioned officers and men who fell in the actions in which Neill was engaged. On the pedestal is an inscription, which says that he was “universally acknowledged as the first who stemmed the torrent of rebellion in Bengal. He fell gloriously at the relief of Lucknow, 25th of September, 1857, aged 47.” As this statue stands in one of the chief thoroughfares, it is always disfigured with layers of dust.”

Time has erased all memory of Neill and, perhaps, rightfully so. But to the ruling British he was nothing short of a hero, of the same ilk as men such as Hodson and Nicholson at the relief of Delhi. A Genealogical and Heraldic History of the Landed Gentry of Great Britain records his full name as James George Smith-Neill and notes that he led a “brigade from Cawnpore to the relief of Lucknow, and here, at the carrying of the batteries to the point of the bayonet, on 25 Sept. 1857, at the very moment of complete success, ‘fell’.” The death was widely reported and, back in England, the queen immediately made him Knight Commander of the Order of the Bath (KCB). The East India Company gave his wife, Isabella, a grant of £500 a year.

He having been a colonel of the Madras Fusiliers, Governor Lord Harris called for a public meeting in the city in December 1857 and a committee was formed to erect a memorial for Smith-Neill (the hyphenated name appears to have been abbreviated later). Poems were published exhorting the public to contribute. Lord Canning, the Governor-General, asked the Commander-in-Chief, Lord Low, to set up a committee in Calcutta for collecting funds and Rs 18,953 was collected by November 1858. Mathew Noble, the well-known sculptor in England was selected for the task. The statue was initially planned as an equestrian one, but this was later given up in favour of Neill standing in an attitude of command. An identical bronze was also commissioned for his birthplace, Ayr in Scotland, and this was unveiled in 1859, in a glittering public ceremony.

Details of when and how the statue was unveiled in Madras are not available in the public domain, but it must have been a huge event. The arrival of the Madras Fusiliers after the Uprising of 1857 had been quelled is recorded in great detail – the public lined up on both sides of the road beginning from Parry’s office and ending at the Royapuram terminus. Speeches on behalf of the British and Indian residents of Madras were read and gifts of silver plate were made. Neill’s statue must have been equally well received.

The statue remained where it was unveiled and became a landmark. R.K. Narayan recalled that it stood “surveying superciliously the native population flowing past.” The British he said had erected the statue with a dual purpose – to immortalise their hero and also remind Indians to behave themselves. Many Mount Road descriptions of the late 19th and early 20th Centuries mention it. It was a convenient spot to mark distances from. But at the same time, there was a growing awareness that Neill was not such a hero after all.

Stories of his cruelty began doing the rounds. In Benares, when his regiment and he had to board a train, there was a delay in many of the men arriving on the platform. The stationmaster pointed out that the train had to leave on time whereupon Neill ordered his arrest. In Kanpur, Neill ordered the summary execution of any Indian who was even remotely suspected of being involved in the Sati Chowra Ghat episode in which several of the English were fired upon when they were boarding boats after they had been promised safe passage. The survivors, chiefly women and children, had been pushed into a well at a place called the Bibighar and left to die. Indian historians would hotly dispute such an occurrence but to men like Neill, these were real crimes that demanded retribution. Several were killed as a consequence. Soon Indian circles were referring to him as the ‘Butcher of Kanpur’. He was also known to have fudged records to tarnish the image of his predecessors who handled the siege of Lucknow, particularly General Havelock.

By 1927, the Freedom Movement had gained considerable ground. Neill’s statue was symbolic of all the oppression that was being fought. P. Kandaswamy’s book, the Political Career of K. Kamaraj, has more details. The Madras Mahajana Sabha and the Madras District Congress Committee passed resolutions calling for the removal of the statue. Somayajulu of Tirunelveli and Swaminatha Mudaliar of Gudiyatham led batches of volunteers to stage protests in front of the statue and also to attempt to deface it. The police was sent in strength to protect it and arrests were made. Some of those apprehended were even sentenced to a year’s rigorous imprisonment. The Freedom Fighters’ Who’s Who, a parallel publication to the more conventional Who’s Who that listed bureaucrats, landed gentry and businessmen, included the names of Lakshmiah and Logiah Naidu who were arrested and served a prison sentence of six months for damaging the statue. By September 1927, six weeks into the agitation, the battle had hotted up and many of the leaders were in gaol. K. Kamaraj was entrusted with the task of leading the Satyagraha. In the Legislative Council, Kamaraj’s mentor, S. Satyamurti thundered that Neill was a “monster in human form whose statue disfigures one of the finest thoroughfares in the city of Madras.”

Before embarking on the protest, Kamaraj took the blessings of Mahatma Gandhi, who was then staying at Amjad Baugh, the Luz Church Road residence of Sriman Srinivasa Iyengar. Gandhi, for his part, gave his blessings with the condition that the protests must conform to the principles of Satyagraha. He also wrote in Young India about why the protest was important (see alongside). But just as the authorities braced themselves for a fresh onslaught on Neill, it was given up. The Simon Commission had diverted the attention of the Congress.

Neill continued to stand on Mount Road until 1937 when, with the formation of the Madras Legislative Assembly, the Rajaji Government was sworn in. “There are more ways than one of keeping a historic monument or memorial,” was that statesman’s cryptic comment even as he ordered the shunting of the statue to the Museum. This was completed one dark November night. Madras holds the record of being the first city in India to have removed a colonial statue and this was even before Independence. The pedestal must have been demolished. The statue still survives in the museum where it kept company temporarily with other worthies such as Kings Edward VII and George V, and Kannagi, before they all moved on to other spots, more in the public eye.

Neill’s statue features in R.K. Narayan’s article, A Matter of Statues, in which he dwelt on the futility of such monuments and the heartburn they cause posterity. Madras that is Chennai has not taken that sage wisdom to heart if we are to go by what has happened since to several statues here.

MEN of Madras, to you I make appeal

For your own hero, while your hearts are warm

With admiration such men do not swarm

Upon life’s common ways. Show what you feel:

Erect the Statue; men to heroes kneel

That sokker head, that monumental form

Which God like towered above Rebellion’s storm.

Raise it, to show your sons what man was Neill!

Erect the statue of our Lion heart

Upon some lofty cenotoph, raised wide,

Where all may reverence, through the Sculptor’s Art.

Their own dear hero’s image glorified:

But write down nothing. Never can depart

From grateful memory how he lived and died.

An appeal