Registered with the Registrar of Newspapers for India under R.N.I 53640/91

Vol. XXVIII No. 1, April 16-30, 2018

Tapping green resources for self-sufficiency

Meera Srikant

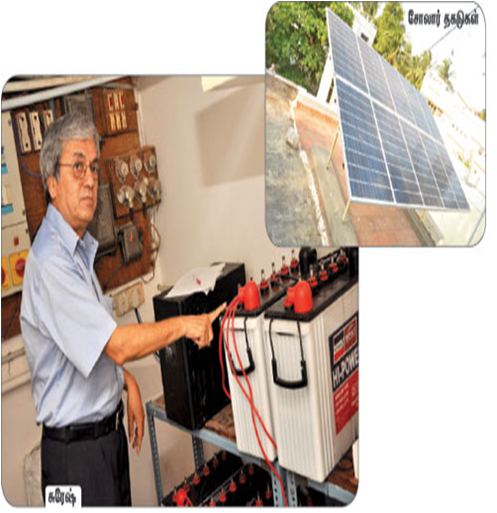

‘Solar’ Suresh points to the Solar batteries that are usually charged during the day.

Above: The eyecatching solar panel.

On his travels abroad, especially in Germany, D. Suresh saw homes with solar panels. Intrigued, he decided to try generating power on his own for his house in Chennai. He started with 1 kW in 2012, and upgraded it to 3 kW capacity four years ago. The unit supplies power to one air-conditioner, the water pump, refrigerator, lights, fans, TV, computer, laptop, washing machine and mixer-grinder. Little wonder that he is popularly known as Solar Suresh.

Since Suresh installed the facility, his home has not been affected by power cuts as he is able to generate around 12 to 16 units a day. “Since the power generated also charges solar batteries, I get power even at night and on rainy days,” he points out. He saves on electricity costs, and hikes in tariffs don’t bother him. The process of generating electricity is free for the lifespan of the panels. “In short, I get 6 per cent tax-free returns on my investment, including expenses on battery replacement,” he says.

Suresh advocates the use of solar energy which is non-polluting, consumes no fossil fuel and also saves foreign exchange for the country. To generate 1 kW of power, all you need is a shade-free area of about 80 sq.ft. With the power produced, most household gadgets can be run, except water heaters and regular ACs. The total investment needed is somewhere around Rs 90,000-Rs 100,000 without accounting for the cost of the battery, and Rs 16, 000 to Rs 18,000 with that. The Central Government provides the panels at a subsidised cost to encourage the tapping of this energy source.

Maintenance is also easy – panels need to be cleaned once in a month or two, just like doors and windows are cleaned. For tubular batteries, the distilled water has to be replaced once in two or three months.

Seeing that Suresh has succeeded not only in being independent of the grid but also in generating excess power, the government has introduced a scheme called net metering. The solar power generated can be fed into the grid and credit obtained for it. This is adjusted against night consumption from the grid and translates as monetary savings for households. The drawback of this scheme is that, if, during the day there is a power cut, the solar power too will fail. Solar battery backup is not possible. With this in mind, Suresh prefers to remain off the grid.

* * *

Suresh came into contact with a person who had expertise in biogas generation using kitchen waste, and decided to try that too. He took it up not just to generate cooking fuel, but as a means of managing his kitchen waste. “In fact, the distance from the biogas unit to my kitchen is longer than prescribed, but I was happy to experiment,” he says.

Suresh installed a biogas plant of one cubic metre capacity in his backyard in a shade-free space, and uses four kilograms of kitchen vegetable waste a day (more can be used) to produce about 20 kg of gas per month. Since the household of two people does not generate enough kitchen waste, he scouts the neighbourhood and vegetable shops to collect food waste to go into the unit where the bacteria from cow dung added at the time of installation converts it to methane. The biogas unit is connected by a pipeline to a special gas stove in the kitchen.

“It can also be used to generate electricity in large complexes and industries,” Suresh says. The unit also generates slurry, which he dilutes and uses for his garden. A word of caution – non-vegetarian waste, leaves from the garden and citrus food waste cannot be added to the unit.

Sintex and similar brands have biogas units to meet different needs. To be able to use the gas generated in this way, a special burner with large holes is needed since the pressure is low. This can slow down cooking, but with boosters, the pressure can be improved. Use of biogas can bring down the use of LPG cylinders dramatically.

To generate 14 kg of gas (the average weight of an LPG cylinder), three to four kilograms of waste are required a day. The waste needs to be cut into pieces, soaked in water and fed into the system. There is a one-time expense of Rs. 40,000-50,000, but there are no maintenance or operational costs. At hotels and hostels where waste generation is more than 200 kg, a more sophisticated system can be installed.

* * *

Ever the pioneer, Suresh started rainwater harvesting (RWH) 20 years ago, even before the government mandated it. He drilled holes in places where water was stagnating and fitted in slotted pipes to let it drain into the soil below and recharge the groundwater table. “There is so much of water under my house now that I had to raise my floor,” he says.

Many buildings installed RWH systems simply to meet minimum requisite complaints with norms, rather than to reap benefits. While his neighbours need to dig deep to find groundwater, he can tap into it at just 10 feet. “All I do, before the commencement of the monsoon is to clean the terrace. The water passes through an organic filter with pebbles, charcoal and sand, which is cleaned every year. No other maintenance is needed,” he explains.

* * *

Suresh also has a terrace garden and has fenced his house with bamboo poles and creepers to produce a forest-like effect. “I don’t need to see the road outside – or experience pollution,” he says. (Courtesy: Grassroots)

Note: Suresh can be contacted at sureshd157@gmail.com