Registered with the Registrar of Newspapers for India under R.N.I 53640/91

Vol. XXVIII No. 11, September 16-30, 2018

My days with Father – Pothan Joseph

Excerpts from 'One Woman's India' by Anna Varki

Many girls think their fathers are special, but I can honestly say that mine was a truly remarkable individual. Details of his colourful life and adventures can be found in other publications (such as those written by T.J.S George), as my father, was a well-known journalist of yesteryear, when India had 562 native states, the larger states having their own currency and army. I will narrate only some anecdotes as we go along with my story.

Before my father left for his trip to London, the Maharaja of Patiala had promised that he would start a newspaper with my father as editor on his return. Part of the deal was that my father would help the Maharaja secure a 21-gun salute, which was the highest honour accorded to a person. At that time, the Maharaja was only allowed a 19-gun salute. My father who knew prominent people such as L.F. Rushbrook Williams, cbe, frsa, succeeded in getting the honour approved for the Maharaja. Alas, by the time my father returned to the shores of Bombay, the Maharaja had fallen very ill and did not live to enjoy the honour. The promise to start a newspaper also remained unfulfilled because of the successor’s refusal for want of a written agreement. I remember only a few lines of the famous article, or rather letter, to the Maharaja, which my father wrote, expressing his disappointment: “Let it not be said that there arose a Pharaoh who knew not a Joseph!” My father was referring to the story in the Bible about Joseph, where the Pharaoh of Egypt recognised the faithfulness of his slave and rewarded him.

Maharajas gave importance to journalists and the press, lest anything adverse be published about them. Journalists were quite often invited for an audience and so it was that the Nizam of Hyderabad, Osman Ali Khan, once invited my father in 1931, or perhaps 1932. Thrilled by the invitation, he went to the King Koti Palace in Hyderabad to meet him. Once there, he was first led by the dharwan to a room and was asked to wait. After some time, he was ushered into a beautiful palatial room that was dimly lit. He couldn’t see anybody. All of a sudden, a resonant voice hailed him and said, “Mr. Joseph, are you looking for the Nizam? Well, here I am.” The Nizam, bejewelled and seated on a throne, extended his hand. It was customary for those granted an audience to present the Nizam with a nazar, usually a gold coin. My father felt embarrassed, as he had forgotten to bring the nazar. “Don’t worry if you have not brought the nazar. I will excuse you. I know you are a journalist,” the Nizam said and gave him a timepiece, which remained on my father’s table till he passed away!

* * *

Father at one time was editing a fiercely nationalist paper called Indian National Herald, now defunct. He was poor at managing finances and so he asked Sarojini Naidu to join him. He made her the chairperson of the board, believing that a woman could handle finances better. But they eventually incurred enormous debt and were hauled up in court. I don’t remember the exact amount which they had to repay, but in that day and age, it was a huge sum, which they took a long time to repay.

My father then took it into his head to stand as a candidate for the Bombay Municipal elections, which he won. The symbol on the election publicity card was his car, a Ford that had to be started by a hand crank, as there were no self-starting cars at that time. My brother and I used to love to get into the car and squeeze the car horn, shaped like a rubber ball, making a honking sound.

One day when I was in my teens and we were in Delhi, Father announced “Today your mother and I are going to see Gandhiji.” “What about me? I too want to see him,” I said. “No. That is just not possible. He is very busy now. Someday when you grow up I will take you to see Gandhiji, may be in his ashram,” Father said. I was very disappointed and angry.

Year later, Father did keep his promise. After my graduation from Queen Mary’s College, Madras, I was on a holiday in Delhi with my parents. Father had moved to Delhi to join the newspaper The Dawn, which was a newspaper owned by Jinnah, the leader of the Muslim League at the time.

One afternoon, Father came home early and asked me to get ready. He was going to take me to see Gandhiji, who was at that time staying in the Bhangi Colony in Delhi. There was a cottage specially built for him. Sarojini Naidu very often stayed with him in Bhangi Colony. My father warned me that there would be many people around Gandhiji and that I was not to rush or draw closer to talk to him. But I bided my time! As we drew closer and Gandhiji saw us, he gave us a warm smile! He was busy spinning on his charkha and talking to people around him. We waited patiently. At the stroke of five, he rose, and picked up a long bamboo pole that helped him take long strides. He beckoned me and put his arms around me, and said, “When you grow up I want you to make a promise to serve your country in whatever way you can.” Then with a long stride, he marched forward with many followers. I will never forget that day!

When I was to be married, my father sent Gandhiji an invitation and he replied with a letter saying, “So your daughter Cookie is getting married. May she be of service to both God and man.” One of the greatest regrets of my life is that this letter, written on handmade paper in Gandhiji’s handwriting, was lost sometime during our various moves. I feel it was very stupid of me, since that letter from Gandhiji to me was worth more than all the gold in the world, something I deemed a legacy, now lost forever!

By the time I was 10, we had moved to Delhi, where my father took over the editorship of Hindustan Times, a paper belonging to the Birla brothers, well-known industrialists of the time. When he started there, he brought with him a young man named Shankar Pillai, who had been working in a steamship company in Bombay. When we were in Bombay, Shankar would visit my father off and on and bring along cartoon sketches he had drawn. My father was impressed with these; cartoons had not yet been introduced in newspapers in India at that time. So, he asked Shankar to join the Hindustan Times as well. That’s how Shankar and his family moved to Delhi, and his cartoons when incorporated into the publication, were a great success.

A telephone connection was a luxury in those days. My father was not very fond of telephone conversations; he would rather have people meet him in person. He did not like making or receiving business calls; instead, he would telephone from the office to ask my brother to sing a hymn to him over the telephone, like ‘Abide with Me’. In one of his daily columns ‘Over a Cup of Tea’, which became a must-read among the populace and followed him to most of the newspapers, he once wrote: “Jaiboy, my son, you are a wonderful lad, always a joy and never a cad.”

* * *

During the war years, Winston Churchill was the Prime Minister of England and he was well known for his ‘V’ for victory sign. Miss Myers, a thorough British woman, with the help of some students, gathered a lot of seashells, big and small, and had a huge ‘V’ sign made on the front lawn of Queen Mary’s College. One night, during the Quit India movement, some of us came out late at night and broke it all up! Miss Myers was furious but could not pinpoint the culprits! The shells had to be gathered up and thrown way!

My father left the Indian Express after a short period of uncertainty and moved to Calcutta to join the Star of India, a Muslim League paper sponsored by the Ispahani group.

My father was not for partition of the country but he believed that there was a case for the Muslims. He left the Star of India, and when Jinnah offered him the editorship of the Dawn, he accepted the offer without hesitation. His answer to anyone who questioned him about his switch of loyalty from the nationalist camp to the Muslim League camp headed by Jinnah was that journalists were hacks who did someone else’s bidding. As far as he was concerned, joining the Dawn was like a lawyer who argued for whatever brief was in front of him.

My father then received a letter from Gandhiji. It read “My dear Pothan, why have you left us? I am a poor man. I need to read what you write, so don’t fail to send me a copy of Dawn. -Mohandas Gandhi”. This letter too has unfortunately not been preserved, something I regret strongly! We have lost most of these memorabilia, because my father never believed in preserving anything! He once said: “a rolling stone has no need for any moss”.

My father felt that many things said by Jinnah for the cause of Muslims were not adequately publicised. In fact, the national newspapers never published whatever topic Jinnah spoke on! My father knew Jinnah from his days in the Bombay Chronicle, when Jinnah was a practising lawyer and a Congressman!

* * *

One night, my father woke me up: “Get up and take this down. Ba has passed away.” (Ba was Gandhiji’s wife). I was really very sleepy and asked him if he had got a message from the office.

During those days, messages from the Reuters and the Associated Press came on the teleprinter of the office and, if urgent, were sent to the house. His reply was, “No, don’t waste any time!” He had a premonition and decided to write accordingly. So, I reluctantly got up and wrote what he dictated – an obituary on Ba – and as he was dictating the content, a message came from the office that his premonition was right: Ba was no more! Next day, the early morning edition of Dawn was the only paper carrying the news of Ba’s passing away, along with my father’s obituary. Jinnah had not raised any objection or query to its publication!

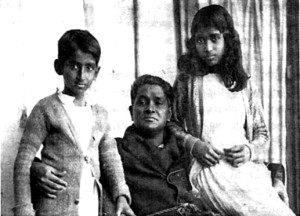

The author and her brother with their father, Pothan Joseph.

A tribute to Pothan Joseph

Pothan Joseph wrote in a style that any contemporary journalist or writer might envy. There was a biblical simplicity and elegance in his writing. Though his sentences were not necessarily short he did not indulge in verbiage.

Above all, what distinguishes his writing from that of his eminent contemporaries was that he had wit. In an age when solemnity was the motto of the journalists and editors, Pothan Joseph brought laughter into the limelight. There was a strong satarical element (with Malayali flavour) in him and he could never be pompous. If anything, he was self-deprecatory in his estimation of himself or his profession.

Unlike other stalwarts, Joseph cared for his fellow journalists who were very often underpaid and told that “journalism is a mission”. The hypocrisy of this high-mindedness showed in the fact that salary of the editors who professed this was often 20 or 30 times those of the reporters and sub-editors.

Joseph’s famous column “Over a Cup of Tea” was a sensation in Delhi. Stylish and sophisticated, it was popular with the ruling class of the time as well as with the general reader. More than just pleasant morning reading, it was also a collector of mores and an Irish keeper of national moods. New in range of appeal and degree of impact. According to TJS George there has been nothing like this in journalism. The column ran steadily for 40 years in the Hindustan Times, then Indian Express and finally the Deccan Herald.

Pothan Joseph was a bohemian. He mixed with high society as comfortably as with people lower down the social scale. Though he knew the powerful, his genuine sympathies were with the lowly.

– Abu Abraham