Registered with the Registrar of Newspapers for India under R.N.I 53640/91

Vol. XXVIII No. 14, November 1-15, 2018

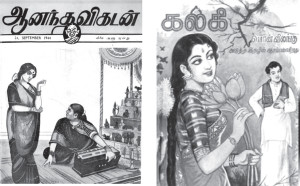

From staid to daring

Once upon a time…

Once upon a time…If Tamil publications of the 1950s had a staid and decorously clad Bharatiya nari (Indian woman), or a conscientious, God-fearing middle-class man on their covers, today’s feature a typical, fashion-conscious, daringly clad college girl leading a ‘fast’ life. Is the media reflecting social changes, or society being influenced by media depictions? It’s a moot point. Strangely enough, alongside the ‘progress’ in terms of modernity and ‘liberation’ that the magazines reflect today, there is also evident, a more daring manifestation of sexism, which ‘modernity’ frowns upon, says Sakuntala Narasimhan of an unbelievable metamorphosis.

Growing up in Delhi in the post-Independence years, I learned to read my mother tongue, Tamil, only through magazines like Ananda Vikatan and Kalki, two popular weeklies that my mother subscribed to. Legendary Tamil writers like Kalki (Krishnamurthy), Lakshmi, R. Choodamani, and Jayakanthan had their novels serialised in these magazines, and I remember Alai Osai, Ponniyin Selvan, Pareesukku Po and other long stories that enjoyed avid readership. Some were social novels, some historical, but the language was uniformly gripping and – and more to the point – grammatically pure and correct.

Vikatan‘s cover always had a nice cartoon illustrating a joke; there was very little about cinema or film actors and actresses. Illustrations were often by the gifted ‘Silpi’, who created masterpiece reproductions of temple sculptures and intricate depictions of historical figures to match a story’s narrative.

Half a century later, when I pick up current issues of these magazines, I am struck by the changes, in content, layout, choice of subjects and general get-up. If the publications of the 1950s had a staid and decorously called Bharatiya nari (Indian woman), or a conscientious, God-fearing middle-class man, today’s feature a typical, fashion-conscious, daringly clad college girl leading a ‘fast life’.

Is the media reflecting social changes, or society being influenced by media depictions? It’s a moot point. Strangely enough, alongside the ‘progress’ in terms of modernity and ‘liberation’ that the magazines reflect today, there is also evident, a more daring manifestation of sexism (which ‘modernity’ frowns upon).

The language, for one – grammar and adherence to linguistic norms, go for a toss. Not just colloquialism, but downright hybrid ‘masala mixtures’, call it a textual equivalent of chaat-masala and pani-puri (not part of South Indian cuisine originally, but even wedding receptions offer these North Indian imports today, in the name of ‘trendiness’).

Here’s a sampling of sentences from today’s pages: “Okay vaa?” (Is it okay, written in Tamil script). “Sooper” (again, written in Tamil letters, in place of what would have been 50 years ago, Sari (all right) or Pramaadam (super). Worlds like naatla, veetla, and roadla, which would have been naattil, veettil and theruvil originally, have taken on new, ‘modern’ inflections.

Appadi illanga (it is not like that), a film director says now, in an interview, the way a lower class, semi-literate person would say it; that would have been, correctly, Appadi illai, in a magazine of yesteryear. Paaraattitta ought to be paaraatti vittaal. And so on. Kondaaduranga (they are celebrating) would have been previously Kondaadugiraargal. Partly, it is perhaps a dilution of Brahminical-literary styles, in favour of commonly spoken, caste-less phrases. Partly, it is also a reflection of the ‘anglicisation’ of urban lifestyles and speech. ‘Creativity illai‘ (there is no creativity), one phrase says. Isn’t there a word for creativity in Tamil?

Curiously, there is no ‘Hindi-isation’ or admixture, in tandem with the Anglicisation – whereas even ads for national entities like the Life Insurance Corporation, or multinationals, routinely use Hindi phrases like aap ke liye and jawaab nahin in their ads. Interesting! There’s grist here, for political/social/North-South research…

Then the pictures – women in shorts, short skirts, knee-length boots, striking sexy poses, with hair left open and no pottu (bindi) on the cover – not done, just not done, in a ‘family magazine’ commanding a wide circulation (including South Indian readers settled in the north). Two generations ago, decent females did not leave their hair open, much less cut it, and being without a bindi was, well, considered sacrilegious and sinful for Hindu women other than widows; as for showing leg – only women of loose morals did.

The magazines would have promptly lost circulation and readership with such depictions, during my mother’s time. Now, perhaps, these are the images that sell. Even salwar-kameez was not acceptable once (I used to wear salwar-kameez to play tennis, and that was supposed to be scandalous in the South, even during the late 1950s when I entered college.)

The recipe page offers chaat (unknown in the South, at one time) and pizza as ‘special’ treats. The titles and subtitles for features are ‘In box’ (written in Tamil script of course) and ‘Visual corner’. ‘TV corner’ is the title of one section (my mother-in-law would not have understood the word corner). “Lights on’ is the title for another section (on filmi gossip). English words proliferate. One article is on Beyonce (that’s globalisation for you) with a picture that would have never been seen in these magazines half a century ago.

A recent issue of Kumudam, another popular weekly, has ‘Women who smoke’ as its lead story, with a young woman on the cover to match, with saree carefully pulled down to expose a breast.

The trend started perhaps three decades ago, with the rise of writers like Sivasankari and ‘Sujatha’ (whose serialised fiction commanded a huge fan following and turned them into social icons). Their novels were gripping and were enjoyed for the plots’ conception rather than literary merit. Nonetheless, the language still remained largely uncorrupted, and faithful to the South Indian ethos. That has changed dramatically, in the New Millennium.

There are still a few Tamil literary magazines, untouched by these trends, but they are by no means ‘mainstream’ or popular in the sense of wide readership. Which is perhaps true of other languages too (including English). Is that a good thing? Had one of today’s issues of Ananda Vikatan been available when I was in school, trying to learn Tamil, I would have been confused by the hybridisation of the written word – part English, part colloquial, and part a genetically modified version of regional writing.

A requiem for something wholesome that is gone, or a hailing of something more in keeping with today’s confused times? That brings us back, then, to that earlier question: Do publications reflect the times or mould them through what the older generation would call a ‘corruption’ of language, themes and presentation? (Courtesy: RIND Survey.)