Registered with the Registrar of Newspapers for India under R.N.I 53640/91

Vol. XXIX No. 21 , February 16-29, 2020

Lost Landmarks of Chennai

by Sriram V

Of Wood Wharves and Firewood Bankshalls

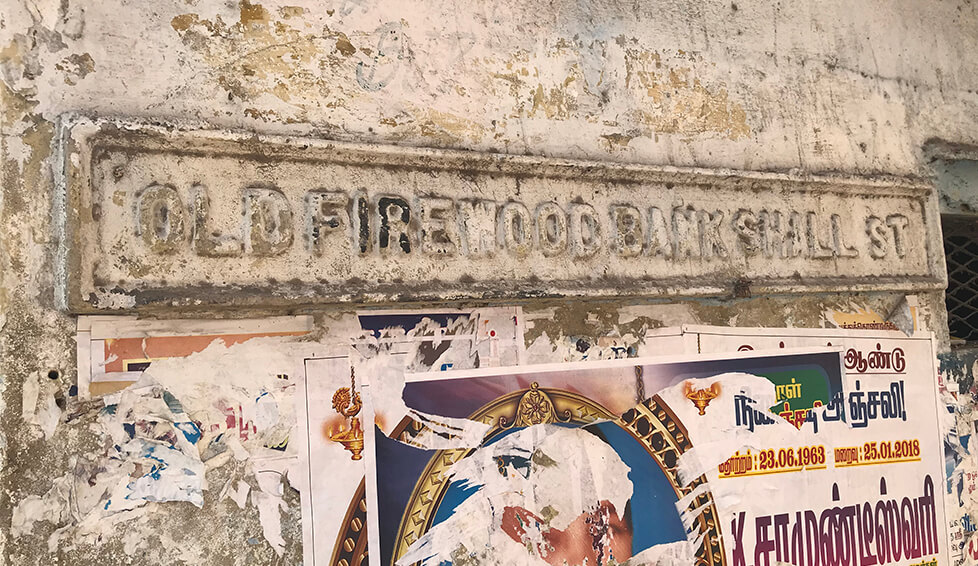

The signboard that you see in the adjoining picture is what triggered off this article. Tiring of going down the same route on the beach each morning, my friend and I walked into the arch that leads from the Marina to the Triplicane Sri Parthasarathi temple via Ayodhya Kuppam (now Nagar). The ancient signboard (is it of wood or concrete?) caught my attention. Old Firewood Bankshall Street is what it reads and that implies there is a new one (there really is one by the way). Both the old and the new, located in the Mattan Kuppam area of Triplicane, are now known as Firewood Bank Streets, the word Bankshall no doubt puzzling the street name signboard makers. But they are in august company – even in the 1930s Bankshall was a forgotten term and these were named Old and New Firewood Bank Stall Streets. The old thoroughfare itself runs for a short distance, parallel to Buckingham Canal. By surviving for so long it brought to mind a whole era gone by, when firewood was such an important aspect of daily life.

Economic Development and Environmental History in the Anthropocene (Bloomsbury and edited by Gareth Austin) has an article titled Forests and a New Energy Economy in 19th Century South India by Prasannan Parthasarathi which looks at the insatiable demand for firewood in Madras. The most obvious requirement was for domestic cooking and water heating purposes but this according to the author was a negligible quantum. Far higher was the demand from brick kilns that proliferated in the periphery of the city which catered to all the Indo-Saracenic building projects that were coming up. These invariably used exposed brick which meant they had to be fired to far greater temperatures than those covered by chunam, so that they could withstand the harsh climate. This demanded great quantities of firewood. Many of the industrial establishments needed steam power, and that included the construction of the Madras harbour. This came from burning wood. The same was also used in steam locomotives. As a consequence, the city literally gobbled up firewood.

While this insatiable appetite did worry some early environmentalists, as catering to it involved felling many forests, the more commercial minded among the East India Company servants began mulling over ways and means of meeting the requirement. Forests in the Presidency were identified and more importantly, the cultivation of casuarina was encouraged, especially in the coastal areas. The area in the vicinity of the Pulicat Lake, to the north of the city, and along what is presently East Coast Road, to the south, became the principal sources of this wood. Moving the logged timber into Madras was the next challenge and this is where the Buckingham Canal and all the older waterways that eventually merged into it, proved useful.

The first of these was Cochrane’s Canal, named after Basil Cochrane (1753-1826), who having entered East India Company service at the age of sixteen rose sufficiently enough to practically corner the victualling contracts for the British Navy in and around Madras. Soon his interests spread to other supplies as well and this is how he became interested in getting a canal built from Pulicat to the northern extreme of the city, chiefly to move firewood. He financed it and work began in 1803, ending in 1806. Officially known as Clive’s Canal after the then Governor, Edward, the Second Lord Clive, it was known only as Cochrane’s locally. The waterway terminated near Basin Bridge at what was known as Wood Wharf, a name that still survives near the northern end of Wall Tax Road. In fact, there are many lanes under the area marked Wood Wharf and all of them end in what was once a boating jetty. Timber and firewood were stored here and later made their way further into the city. This is also the reason why Sydenham’s Road and the surrounding areas still remain the headquarters of the timber business in the city.

Heavy felling of timber in Sriharikota and other places along the Pulicat soon saw the area being denuded and attention then shifted to the south of the city. Work began on the South Canal in 1852 and was completed in 1857, this waterway linking the Adyar to the mouth of the Palar. This became the secondary source of supply of casuarina to the city. By the 1870s, digging began as a famine relief measure, for linking the north and south canals via the city. This was named after the then Governor, the Duke of Buckingham and Chandos and eventually the entire waterway, from Pulicat to the Palar came to be known by that name. The principal residential areas through which the Buckingham Canal wound its way in the city soon had markets coming up along the banks. The most famous among these was of course the Tanneer Thurai (waterside) market in Mylapore (see Lost Landmarks MM Vol. XXVII No. 14, Nov. 1st, 2014) but lesser known was the huge Firewood Bankshall that came up in Triplicane.

Also forgotten is the timber yard that existed for long near the Barber’s (now Ambedkar) Bridge at the eastern end of Edward Elliot’s Road (now S Radhakrishnan Salai), which has since made way for the Citi Centre Mall. Rumour has it that it was either here, or in the coconut grove that existed alongside (now the Police Quarters), that stalwarts of the non-Brahmin movement met for the first time, to found the South Indian Liberation Front aka Justice Party.

It is very likely that the Old Firewood Bankshall Street, by virtue of its name, predates the Buckingham Canal and was a location from where firewood was loaded via catamarans to the waiting ships at Madras Roads. Both old and new are however practically on the bank of the canal.

The heyday for firewood supply to Madras was in the mid 19th century. In 1852, the quantity was as high as 98,000 tonnes (Hugh Cleghorn, Forests and Gardens of South India) and yet it is in this same year that The India Directory warns that while water is excellent in Madras (!!!) and all sorts of provisions may be had for ships, firewood is scarce. Articles of the period show that not one part of the casuarina was allowed to go waste – the stumps and roots left behind after cutting commanded a price and there was a further informal industry in following the pathways of carts that carried the wood through the city – twigs and slivers that fell off were collected for firewood as well. The demand had by 1882 (Sir Dietrich Brandis – Suggestions Regarding Forest Administration in Madras Presidency), come down to 63,000 tonnes, of which 47,000 was coming in by water. Industrial requirements for firewood reduced by the early 20th century. Domestic requirements however continued to remain high. By then, a tramway 13 miles long brought timber to the Pulicat Lake from neighbouring villages for onward shipment via the canal.

With areas under cultivation of casuarina not increasing, the city began facing shortages of firewood by the time of the Second World War. That was when the population in Madras doubled. The Government had to resort to rationing of firewood at one pound per day per capita. A black market immediately came up and flourished. The rationing continued well into the 1950s and beyond. As late as in the 1960s, the Government was lamenting over the dependence on the canal for the supply of firewood and the shortage of this commodity. Kerosene, also a rationed commodity and available since the late 1800s was rapidly becoming an alternative and by the 1960s, liquefied petroleum gas (LPG) had arrived on the scene. Typically, domestic households were reluctant to try this new option for a while but it did catch on. The more traditional eateries and larger social gatherings such as weddings continued to use firewood. But by the 1980s, cooking gas had taken over.

With the canal having been defunct since the 1960s, the firewood bankshall lost its meaning as did the other wood depots, especially those that catered for fuel requirements. The storehouses began to be put to other use. In a way it was all to the good, for the city cut its usage of wood, even though it had increased its carbon footprint by way of other forms of pollution. There were some who claimed that food never tasted the same thereafter but these were people who never had to bother about the actual cooking!

A word on Bankshalls

In today’s parlance bankshall means nothing. But in the early years of the British empire in India, this was an all important word. The entire trade of the East India Company depended on stocks – of cloth and other articles and these were stored in huge warehouses – known as kidangu-s or pandaga salai-s in Tamil. The Telugu equivalent for kidangu was giddangi and the two, along with the Hindi godaam and the Malay godong probably gave rise to the English word godown. As per HD Love’s Vestiges of Old Madras, pandaga salai morphed into bankshall. It is a term extensively quoted in Company transactions and eventually made its way from Madras to Calcutta which city even now has a Bankshall Street, and the City Sessions Court there now is known as Bankshall Court.

The fishermen of the area in Triplicane wanted to set up a colony to live. By giving up drinking, gambling and other bad habits, they saved Rupees 400 and started a Co-operative society. But the money was not available as the fishermen had other loans and obligations. So in October 1933, Ramnath Goenka helped the colony start up again by giving them Rs. 400. Thus the colony got a start. That is when they decided to name it as Ayodhya Kuppam.

Thank you for this important note. It’s hard to pull yourself up by the bootstraps and Sri Goenka’s few hundred rupees must have been a material and inspirational help.