Registered with the Registrar of Newspapers for India under R.N.I 53640/91

Vol. XXIX No. 22, March 1-15, 2020

Rise of Early Tamil Newspapers through the Swadesamitran Prism

by N.S. Parthasarathy

The entrance to Swadesamitran

The entrance to SwadesamitranThe article by Mrinal Chatterjee on Tamil journals in the MM, July 16-31, 2019, which made references to Swadesamitran, evokes more memories of this once-leading newspaper of its time. In a literal sense, Swadesamitran meant ‘Friend of the Country’.

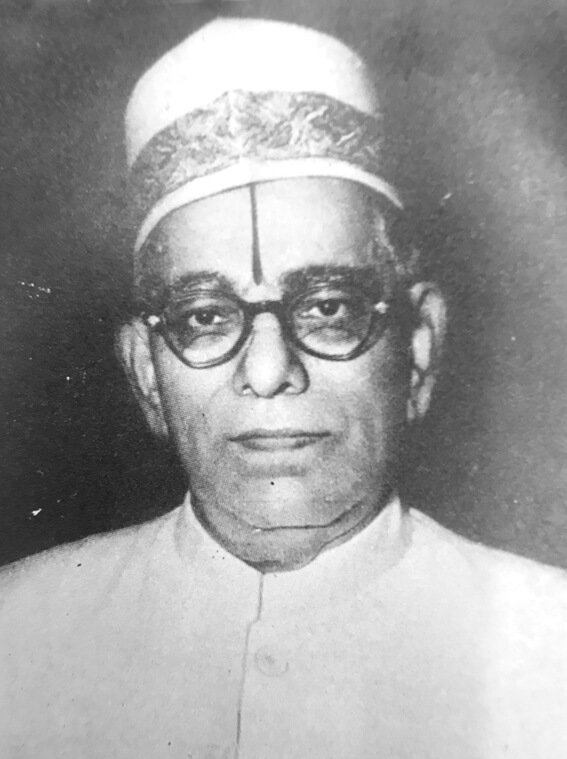

C.R. Srinivasan – Proprietor and Editor, Swadesamitran

C.R. Srinivasan – Proprietor and Editor, SwadesamitranTrue to its name, the paper espoused the cause of freedom from British Rule. A pioneer among language newspapers, its experiences reflect the rise of language journalism in South India.

Swadesamitran was established in 1882, a few years after the likes of Times of India (1861), The Hindu (1878) and Civil & Military Gazette (1872) – the last one was published from Lahore with Rudyard Kipling as editor. Swadesamitran was known endearingly as Mitran. It was perhaps among the oldest vernacular dailies in Asia. Mitran was owned, at the time of our story, by C.R. Srinivasan. Under him, the paper continued the tradition set by earlier illustrious Editors. The paper was sought after by Tamils settled in Ceylon, Malaya and Burma. The poet Subramania Bharathy was sub-editor for the paper for some time.

In the early days, A. Rangaswami Ayyangar served as the Editor to both The Hindu and Swadesamitran. He can be recognised in the historic photo of the Round Table Conference in London along with Gandhiji, wearing a white turban in the south Indian style. A. Rangaswami Ayyangar and N. Gopalaswami Ayyangar were brothers. The latter was Diwan of Kashmir and later, a member of the Nehru Cabinet handling Kashmir affairs. C.R Srinivasan, who took over Mitran, was their nephew.

Chatterjee says that during the Rangaswami Ayyangar days, Swadesamitran was ‘a Tamil version of The Hindu’. In those days, papers could not afford the luxury of a network of their own correspondents in important centres gathering news. News was retailed by Reuters and Press Trust of India to newspapers, and this centrally-fed news formed the main body of papers. As such, the commonness of content was due to the sameness of the source, but that did not make one paper a translation of the other.

Each paper established its uniqueness with editorials and special columns – today, the papers also leverage ‘inside news’ gathered by their own correspondents. It was said that there were occasions of Tamil editorials of Rangaswami Ayyangar for Swadesamitran appearing in English in The Hindu. After Rangaswami Ayyangar, the two papers assumed their independent identities.

The editorial office and press were accommodated there. Financially, language papers were not doing as well as English ones, as the newspaper reading habit was more prevalent among the elite who took to papers like The Hindu, Madras Mail, Times of India and Statesman. The section that read Tamil papers comprised of housewives and rural families. Those wanting to read a newspaper had to go to the nearest pan shop to pick up a copy. As such, there was no mass retail distribution as in present times. Circulation was limited and, consequently, advertising income was meagre and financial viability, fragile.

World War II, Independence and industrial growth brought about big changes. The high tide of this period lifted all boats including those of the language papers. Progression from a small base was overwhelming for language papers as compared to English papers, that were already used to a relatively larger circulation. Mitran found itself having to cater, suddenly, to a large, news-hungry reading public comprising industrial workers, white collar employees, middle class families, home making women and emerging youth.

By then C.R Srinivasan, known as C.R.S, had become the Managing Editor, holding controlling shares of Mitran. His son C.S Narasimhan was a rank-holder with Honours in Economics. He kept up with brilliant fellow students like V.K. Ramaswamy and S. Narasimhan, who rose to the position of Finance Secretary in the central government. When he joined Mitran, it gave C.R.S the confidence to invest in modernising the production and distribution of the paper. Adapting itself to new opportunities, Mitran’s daily version provided news of the world, country and province, while the weekly version treated readers to short stories, serialised novels, puzzles and women’s sections. Writers and music critiques such as Neelam and Sandilyan in Swadesamitran became household names.

Soon after Independence, Mitran could afford to buy the property on Mount Road that was called Victory House, perhaps commemorating victory in World War II. The building was of an ornate red colour with arched, pillared frontage covering the walking path. The built area of the building was the vast ground floor that extended from the front walking promenade on Mount Road on the west side to Ellis Road on the east side. The ground floor was so spacious that after accommodating the staff, composing department, photo studio, printing press, distribution department, store and canteen, there was still space that could be rented out. This space was earmarked on the western side facing Mount Road. This portion was ideal for glass show cases for the public to enjoy window shopping using the covered walking path. This space was in a prime location in the city and the glass-fronted display cases were ideal for showcasing electronic items and ‘white goods’ like refrigerators, electric cookers, ovens and bathroom heaters that were in demand among the emerging professional class. Mohammed Ebrahim and Co., who were pioneers in electronic and white goods, rented out this space for several years. Their prominence on the Mount Road made people think that they were the owners of Victory House.

Acquiring Victory House was made necessary and possible by the rising demand for language papers in urban and interior areas, and even from Tamil residents in Malaya, Singapore and Ceylon. Moving into Victory House marked the coming of age of local language newspapers playing on even terms with the English Press.

C.R.S realised that news should reach people at the soonest and was fond of saying that newspaper delayed was wastepaper. News in the new age had become a highly perishable commodity. Newspaper production and distribution arrangements had to address the challenge of delivering news before it became stale.

On the production side, the problem was that Tamil characters had to be hand-composed letter by letter for the day’s paper. There were far larger number of letters in Tamil and many variants too, in combination with vowels.

Proof reading was equally painful and time consuming. This long lead in getting the day’s paper ready and into the hands of the reader in time meant that the paper was behind events and not up to date when it was delivered. C.R.S was not the inventor of the new streamlined letters with additive signs for vowelizing consonants, but he was the one that found that such an ingenious simplification could be adapted to Lino typing machines. This measure speeded up the composing process in line with English papers. There was hesitation among his senior colleagues who feared that the reading public would be put off by the new forms of characters and would stop buying the paper. C.R.S said the paper would perish if it stuck to the conventional style if it cannot provide the latest news.

(To be continued next fortnight)

Pingback: Blog on From Madras to Chennai: Colonial Transformations – Drishti IAS – Shining a Spotlight on the Latest in News, Entertainment, and Lifestyle at Spotlight.ink