Registered with the Registrar of Newspapers for India under R.N.I 53640/91

Vol. XXX No. No. 15, December 1-15, 2020

A Collector Looks Back

by V.A.K. Ranga Rao

The author is a renowned dance critic, film historian and collector of gramophone records.

I was born in 1939 in Madras to Rajah R.J.K. Ranga Rao, popularly known as the Zamindarof Chikkavaram, and Rani Saraswathi Devi, after two daughters. Delirious and eager to convey the good news to his mother, Father crashed his Ford tourer into the gatepost. We were royalty and childbirth took place at home. This was Orattah, a rented house where the M.O.P. Vaishnav College now stands.

It was a sizzling summer, I have been told. Consequently perhaps. I am still sizzling, now taken up by song-and-dance, now captivated by literature. Happily, these haven’t been childhood pastimes or youthful infatuations. They still hold me tight, enrapture, entangle and inspire me.

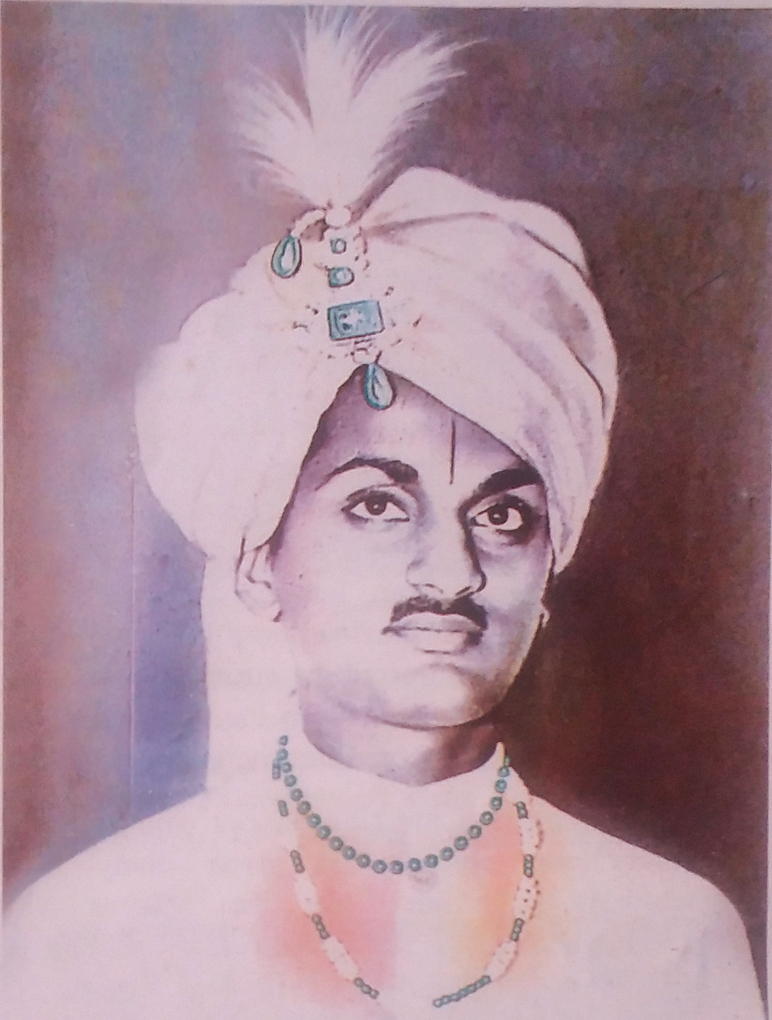

The royal look – on turning a major.

The royal look – on turning a major.I was around three when my mother’s wind-up gramophone (a part of her dowry) fascinated me. Once or twice a week, I would sit still as my mother heard a few 78 rpm records. By the time I was five, I was requesting that particular songs be played for me. By seven, I could do all of it by myself.

Before her marriage, Mother had learnt veena in her native Nuzvid (she was the third daughter of the Zamindar of Telaprole) and retained a taste for records by veena-playing vocalists. But she also had cosmopolitan taste and so, I too developed a liking for a vast variety of music: film songs in Telugu, Hindi and Tamil, in that order. At that age, without any schooling, I had an ear for classical music too but these were limited to songs used for classical dance, mostly in Telugu, but one or two in Tamil and Kannada.

My exposure to classical dance happened when I was four. Bobbili, then in Vizag District and now in Vizianagaram, had a temple to the deity of the royals. Venugopala. A dancer of that temple, Gaddibhuktha Seetharam, was also the court dancer of the Bobbili Estate, whose ruler was my father’s elder brother, R.S.R.K. Ranga Rao, the Rajah of Bobbili, at one time the Premier of Madras Presidency.

Due to this connection, Seetharam finishing her duties at the temple, would come every morning to the ladies’ quarters of the palace where male children also would be housed till their teen years. She would do a few chores for the Rani (Lakshmisubhadra, my mother’s eldest sister).

Afterwards she would gather us children and recite simple poetry, mostly on Krishna. All would disappear after a few minutes, but not me. The previous night, I’d have seen her dance in the deity’s procession around the palace and ask her about them. Thrilled that a five-year old noticed them well enough to question her (that was the start of the critic in me), she would explain to the best of her ability. My other exposure to dance was through film, and on stage, when we were in Madras for three summer months.

For some reason, it was the Hindi film that held me with its songs and dances.

Helen, the eternal naiad, the only item girl all of whose dances you could enjoy with your maiden aunt. Not an inch of exposure (She wore body-stockings) nor a single movement aimed below the belt. Apart from socials and fantasies, she danced in mythologicals too. Her Sundaranga in Bhookailas (K.N. Dandayudhapani Pillai’s choreography) is still a show-stopper after 70 years.

* * *

I am asked frequently when I started my collection (of 42,000 78 rpm records, from 1904 to 1973 when they were discontinued, in 40 national and international languages). I ask them in turn: When did you start learning your mother-tongue?

In the late 1940s I was given Rs. 10 as my weekly pocket money and with it I would purchase two records without fail. I had no idea then that this seed would grow into a banyan tree.

In the early 1970s the manufacture of 78 rpm records was stopped. I bought LPs, EPs, SPs and, a little later, Super-7s but I continued to acquire 78s from second-hand shops. Only those I liked. Then a thought struck me. There were people collecting stamps and rare books apart from match labels and cigarette packs. Then there were individuals and institutions given to repairing and maintaining the houses where the famous poets and composers lived. But there were none collecting 78s (so I thought; happily; I was wrong).

So I started to collect every 78 rpm record I did not have, no matter what the content, language, as long as the disc was in good condition.

In 1980, my parents decided to go on a pilgrimage to certain places in the north. A whole railway saloon was booked. We had a dhobi, two cooks come along. And I had two dealwood boxes made to snugly accommodate 78s. My two school-going nephews, Krishna Kumar and Mahesh Kumar, were with us. They helped me in buying and lugging the records back to our compartment. This happened in Calcutta, Benarass, Allahabad, Lucknow and Amritsar but not in Delhi where the prices were high. Our targets were old record dealers and second-hand markets.

One dealer in Allahabad said that all the unsold 78s were stored in the godown and sent us there with two helpers. After swimming through the dust, we found a stack of records, and picked up thirty or forty. As we spent nearly three hours and returned awash with dust, I thought the prorietor would demand a hefty sum. I hesitantly asked him how much. He simply said “Take them!” At that moment I wished him half the ‘punya’ I gathered in the pilgrimage.

Once before going to Bangalore, I took out advertisements in English, Kannada, Telugu and Urdu dailies, stating that I wanted to buy old 78s, giving my hotel telephone numbers (no cell-phones, 1985). My nephews (the same duo) were studying Engineering there. On their two-wheelers, I would visit the callers’ homes, taking along the file containing the particulars of records I already had. I would acquire whatever I did not have. A few would insist that the whole lot should be taken. Some would ask for a high price. I would

bargain and bring it down to Rs. 10, which I could afford.

Same thing happened on visit to Hyderabad. A distant caller, on reaching told me that he had only six records. I was disappointed but wonder of wonders, four had been on my wish-list for decades! On one of my visits to the National Film Archives of India, I found nearly 300 records with an old dealer in Pune.

Many relatives, friends and strangers parted with their hoards, oft-times even without my asking. This foraging came to a rest by 2000. There were no records available at a reasonable price.

My collection is well-arranged. To start with, classical music…. Western, Hindustani and Carnatic; first the instruments, then the vocalists, in alphabetical order. Non-film records alphabetical again, by the language and the artist. In this, drama sets, folk-songs, dance music (Bharatanatyam, Kathak), comic, mimicry and speeches are some of the categories. And the major section, film records, by the language and title of the film.

Speeches by Gandhiji, Nehru, Madan Mohan Malaviya, Subhash Chandra Bose, Lord Baden-Powell (founder of the Scout Movement), Benito Mussolini (in Italian). Discs of Bose’s INA, songs led by Capt. Laxmi. Recitations of her own poetry by my goddess of verse, Sarojini Devi.

Rare languages? Asian: Nepali, Konkani, Sinhala, Burmese, Badaga, Goan, Chattisgarhi, Christian lyrics and sermons in a dozen tribal languages (Gar etc.) Foreign: English, Italian, Neapolitan, Latin, French, many kinds of Russian and Chinese, Arabic, Portuguese, Spanish, etc.

I wrote columns about gramophone records in Telugu, English and supervised translations in Tamil and Kannada. In Screen weekly from Bombay, I wrote a fortnighty column, The Sounds of Music. In the beginning, the space allotted to it was less than half a page. Within a few months, I was given almost a full page. It covered music in almost all Indian languages, old and new.

It helped me and others discover the fact that there were record-collectors all over the country. Most collected records of one language; some specialised in one genre. Others limited their acquisitions to those of a particular singer or music-director.

One happy result was that associations were established to save old-time records, discuss their content, felicitates the veteran artists. One in Bombay and another in Bangalore flourished with monthly and annual meetings.

In those days Sur Singar Sansad of Bombay was giving two awards annually to film music. One to the song that the unbiased committee considered the most classical, and the second to the film which contained most classically oriented songs.

One year, impressed by the score created by Vijayabhaskar in Malayamarutha (1986, Kannada), I sent a cassette of it to the Sansad. When it won the award that year in the second category. I celebrated it by going up the local St. Thomas Mount and offering prayers.

I was and remain a Hindu, but all my three schools were Christian, institutions – Good Shephered in Madras, Bishop Cottons in Bangalore and Madras Christian College School, Madras. Somehow I associate thanksgiving with Christianity!

What else with my records now? Waiting for an individual/institution to acquire this wealth, along with nearly a thousand books (English, Telugu, Hindi, Tamil, Malayalam, Marathi, Kannada, Bengali, Asamese and Gujarati) on showbiz people, and do one thing I could not do; make it accessible to listeners and researchers.

This collection of 42,000 is the largest collection in the world of 78 rpm records, even if the local media refuse to acknowledge it.

(Excerpted from an article in Sruti)

picture captions: The royal look – on turning a major.

Ranga Rao (standing centre) with his parents and siblings Sridevi, Guruprasad and Mohini.