Registered with the Registrar of Newspapers for India under R.N.I 53640/91

Vol. XXVII No. 11, September 16-30, 2017

Lost landmarks of Chennai

SRIRAM V

Satyamurti’s ‘Sundara’

S. Satyamurti.

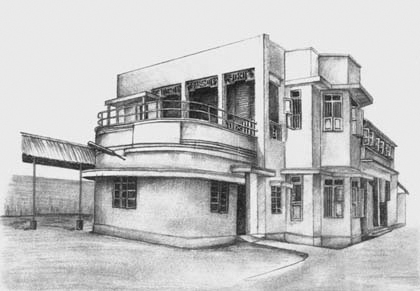

For years it was a sight for sore eyes in increasingly cluttered and congested T’Nagar. Located in a broad section of Thanigachalam Chetty Road, this was a bungalow of the old variety. A garden with a statue, a curving verandah and, if memory serves me right, a central courtyard with a swing. Last month I passed by the house and it was with some shock that I realised it was no longer there. I could have been the central character in Daphne Du Maurier’s Rebecca, going back to look at Manderley. The doors and windows were stacked for sale and a vast empty space had taken over where Sundara once was. The marble plaques in the gateposts proudly gave out the name of the house and of its famed occupant – S. Satyamurti. In one fell swoop, the wreckers had done away with a significant part of Chennai’s history.

For years it was a sight for sore eyes in increasingly cluttered and congested T’Nagar. Located in a broad section of Thanigachalam Chetty Road, this was a bungalow of the old variety. A garden with a statue, a curving verandah and, if memory serves me right, a central courtyard with a swing. Last month I passed by the house and it was with some shock that I realised it was no longer there. I could have been the central character in Daphne Du Maurier’s Rebecca, going back to look at Manderley. The doors and windows were stacked for sale and a vast empty space had taken over where Sundara once was. The marble plaques in the gateposts proudly gave out the name of the house and of its famed occupant – S. Satyamurti. In one fell swoop, the wreckers had done away with a significant part of Chennai’s history.

S. Satyamurti (1887-1943) was a man of many parts. A lawyer by profession, he was an active member of the Suguna Vilasa Sabha, a founder secretary of the Music Academy and a member of the University Senate. A brilliant orator, he was one of prime movers of the Congress Party in Madras Presidency. In that capacity, it was he who first thought of roping in theatre personalities for public meetings. S.G. Kittappa and K.B. Sundarambal, the two stars of the Tamil theatre in the 1920s, were his first choices. That in turn led to film personalities being invited to speak at political meetings, which got them involved with various parties and culminated in the present scenario of Tamil Nadu where every film star aspires for a stint in power.

Satyamurti served as Mayor of Madras in 1939-40. During his tenure he successfully exhorted citizens to voluntarily clean their neighbourhoods. Batches of residents with brooms were a familiar sight long before Swacch Bharath made its appearance. It was also Satyamurti who augmented the water supply of the city, getting the foundation stone laid for the Poondi Reservoir, which would one day bear his name as Satyamurti Sagar.

K.B. Sundarambal.

Many felt that the Congress victory in the polls to the Madras Legislative Assembly in 1937 was due to his efforts and expected him to become the Prime Minister of Madras. But that was not to be. He was, however, elected to the Central Legislature in 1935 and his speeches there livened up many a debate. A brilliant career in public service was cut short following the rigours of Amravati prison where he was interned in 1942 for his participation in the Quit India Movement. Released when his health was beyond recovery, Satyamurti died in the Lansdowne Ward of the General Hospital, Madras.

A life of burning the candle at both ends meant Satyamurti had hardly any time for family, comprising his wife and daughter Lakshmi. It was left to well-wishers to make good. Worried that her honorary brother did not have a house to call his own, K.B. Sundarambal, by then a very well to do theatre and film personality, bought and gifted this plot of land on Thanigachalam Road to Satyamurti. The house was completed in the late 1930s and was named Sundara. It was however always a matter of debate on whether it was named after the benefactress or after Satyamurti’s father Sundara Sastrigal. Does it matter now that the house itself has gone?

After Satyamurti’s time, his daughter lived here with her husband. With the couple also having passed away, the demolition of the house was the only way out for the sons. In a city where the Government does not reward or recognise in any way people who protect heritage, what else can private owners do?