Registered with the Registrar of Newspapers for India under R.N.I 53640/91

Vol. XXVIII No. 22, March 1-15, 2019

Adyar Creek — ready & waiting

By A Special Correspondent

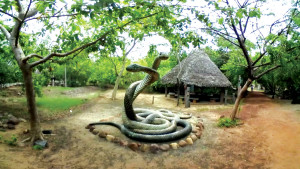

The Adyar Poonga.

For despondency over lethargic progress of improvements to Chennai, a visit to the Adyar Poonga could be an antidote. Adyar Poonga is the beautiful term that stands for the project to rehabilitate and restore the Adyar Creek, the primary and vibrant estuarine system of our City.

At one time, by the vigorous seasonal inflow into the sea and the natural counter-ingress of sea water into the creek and canals, the mud-flats and secluded islands hosted several species of vegetation, insects, organisms, birds and animals, thriving in grand symphonic synergy in an environment of undisturbed Nature. Aided by the biological attributes of the Adyar estuary, fauna and floral diversity flourished and it became a spawning and nursery ground for varieties of fish. All this was disturbed.

Adyar Poonga before and after restoration.

The ruthless urbanisation and consequent emaciation of the river upstream through settlements on its banks, dumping of solid wastes, discharging of industrial effluents and reckless release of untreated sewage by malfunctioning Effluent Treatment Plants sounded the death knell of the Adyar Creek and estuary. An early demonstration of concern over the rapid deterioration and contraction of the Adyar Creek was in the 1950s, when the Department of Fisheries, Government of Tamil Nadu, set up fish and shrimp farms adjacent to the creek, it was one among the first brackish water shrimp farms in South India. The project could not withstand the onslaught of human recklessness and irresponsibility.

A spirited campaign saw the Consumer Action Group taking the Government to Court for wilfully neglecting the Creek. The judgement forced the Government to act. This resulted in the setting up the Adyar Poonga under the Chennai Rivers Restoration Trust (CRRT) in 2008 with a substantial budget. Initially, 58 acres were released of which 40 acres became the restored creek area. CRRT is responsible for coordinating the restoration of the three river systems of Chennai – the Adyar, the Cooum and the Kosasthalaiyar. Dr. Kalai Arasan, heading this organisation, explains that each of the three rivers has its own behavioural characteristic and the Adyar is the most complex demanding their prior attention.

We asked him whether urban intrusion that had already taken place and the poor river flow, quantitatively and qualitatively, were not insuperable impediments to restoration – both being difficult to overcome and almost irreversible. Exuding confidence, he says that the urban incursion and unauthorised settlements are under control and are not a hurdle to rehabilitation. In evidence, he says, now, CRRT in Adyar commands a creek area of 40 acres of creek plus 350 acres in the estuary.

Pollution-free, copious river flow is necessary for the estuarine eco-system to flourish. The estuary and creek had to be cleared, desilted and got ready to receive the river flow. This has by and large been completed. It was a massive operation of removing the heavily overgrown rogue plants, like prosopis juliflora which has obliterated water bodies, desilting and dredging the creek to restore their holding capacity, recreating islands with the silt and dredge, planting, on islands and elsewhere, specially selected varieties of vegetation that thrive in estuarine environment without irrigation or fertilisation, introducing fish species that provide a source of income to fisherfolk in the villages and related measures. The islands provide seclusion for flora and fauna to thrive. In Adyar estuary, around 57,000 mangrove species and 35,000 terrestrial saplings have been planted, removing the invasive species, debris and plastic waste.

Here are some data on the beneficial impact of eco-restoration of the creek by CRRT. Faunal diversity in the Adyar Creek has increased from 273 in 2016-2017 to 331 in 2017-2018. The species of insects – including butterflies and dragonflies – has increased from 98 to 155 in the Creek. As many as eight species of molluscs, 13 crabs, 155 insects, 10 fishes, 10 amphibians, 19 reptiles, 105 birds and 16 animals have been recorded in the Adyar eco-park. Migratory birds have also been sighted some with a pronounced preference for the Adyar Creek, over Vedanthangal, because of availability of more food and the seclusion. In 2015, the study by ICAR-Central Institute of Brackishwater Aquaculture (CIBA) revealed that the biotic and abiotic indicators of the Creek were within the desirable limit and suited for brackish water aquaculture. CRRT’s effort has thus been effective in the estuary ecosystem regaining life.

CRRT has been welcoming and cooperating with agencies and groups capable of contributing expertise – the PWD, Fisheries Department, CIBA, nearby village groups and numerous others. Srinivasapuram, Mallikuppam and Mallimanagar, adjacent to the creek, have been identified as partners in sustainable brackish water aquaculture to supplement livelihood.

The stormwater drain from the surrounding area augments fresh water availability in the Creek. On the other hand, heavy exploitation of groundwater in neighbourhood establishments depresses the water level in the Creek. Flow in the river is weak and of poor quality. Another handicap in maintaining the salinity level in the Creek is the lack of sea water inflow into estuary in summer months because of sand bar formation. Working against such odds CRRT has been successful in reviving the Creek. The budget of Rs. 40 crore has been nearly fully absorbed, spent effectively as even a lay visual inspection of the scenic surroundings demonstrates.

We are cautioned that what is being done is rehabilitation of the Creek and estuary as distinct from restoration. The aim is that rehabilitation would eventually lead to restoration. Experts in estuarine management say that “restoration in the strictest sense is the return of an ecosystem to an exact pre-existing condition following degradation or disruption.” To restore the ecological structure and function of a damaged estuarine system requires considerable time “depending on the type and severity of the human pressure, the kind of habitat, the geographic location of the impacted system, and other factors.” A time span of 12-15 years is needed for a restored site to exhibit similar features as a natural reference site.

The result of the present rehabilitation, which has taken ten years, is, by itself, spectacular except that it needs intervention till eventually the eco-system becomes self-supporting. Those of us who travel from Adyar to San Thomé, may remember that some years ago we passed on our left the massive stinking dump yard which has now become the Poonga. Today, the brackish mix of freshwater and saltwater hosts diversity of animal and plant life. Submerged aquatic vegetation, or seagrass, in the estuary when the Adyar river is restored would provide breeding and nursery grounds for many species of marine life.

Full “restoration” of the Adyar estuary is dependent on the restoration of the upper reaches of the river and restoration of water bodies in the river basin to restore a full pollution free inflow. It is a challenge to keep up the estuary and Creek in a condition, till then, to take advantage of the full flowing Adyar. While the river restoration is still under implementation over the next three years or so, flow of polluted water into the estuary would have the effect of negating efforts to revive and maintain the Creek at considerable cost and effort. Therefore, the dumping must be stopped within a few weeks, as of foremost priority, while the rest of the aspects of river restoration takes its time to complete.

The 40 km Adyar River restoration presents many challenges – clearing settlements and constructions on its banks, dredging and most importantly, stopping the dumping of solid wastes, effluents and sewage. The Adyar, unlike the Cooum or the Kosasthalaiyar has a large basin and water bodies in the basin area used to overflow into the Adyar. Many of these have been taken over by legal and illegal constructions and lost forever. The Government is restoring the capacity of the remaining ones to augment the flow through Adyar in the rainy season.

The estuary has no life independent of the river inflow. It is in this context that reports of enormous delays by multiple agencies of the government are of concern. Keeping up the creek and estuary is difficult if a pollution-free flow in Adyar is delayed. If the sixty odd crore spent on the creek is not to go waste, the Adyar restoration must be completed on highest priority and, meanwhile, the dumping stopped with least possible delay.