Registered with the Registrar of Newspapers for India under R.N.I 53640/91

Vol. XXVIII No. 22, March 1-15, 2019

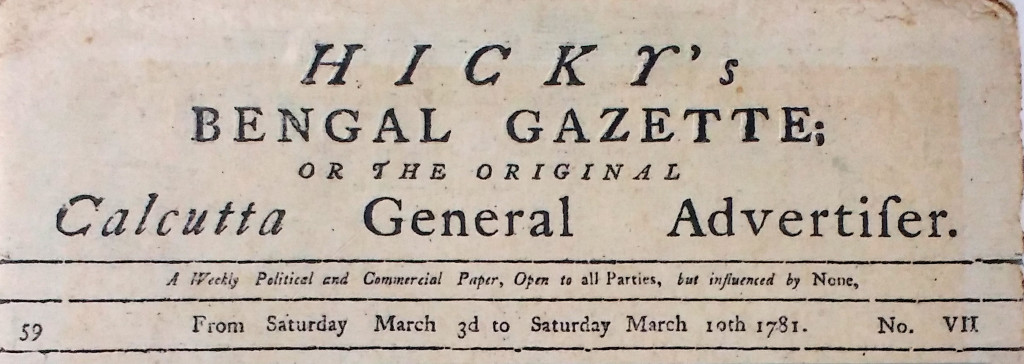

Hicky’s Bengal Gazette

by R.V. Rajan (rvrajan42@gmail.com)

A newspaper with controversy’s seeds in Madras

It happened in 1769 during Warren Hastings’ second voyage to Madras to serve the English East India Company’s Council. Aboard The Duke of Grafton on which Hastings was sailing there was a young couple, the Baron and Baroness Karl von Imhoff. The Baron, who was a portrait painter of sorts, was travelling with his strikingly attractive 22-year-old wife, Maria Chapuset, a woman of wit and intelligence. The combination was just what was necessary to appeal to the retiring widower Hastings.

Warren Hastings.

Maria Hastings.

A poor sailor, Hastings became progressively ill during the nine-month long voyage. Maria nursed him through it all. Nursing changed to intelligent conversation, and a meeting of minds led to Maria Imhoff becoming Warren Hastings’ official hostess aboard the ship.

Once in Madras, Hastings would not only set up house for the Imhoffs but also move in close to them. After ten months in Madras and painting half the settlement, Imhoff wanted to try his luck in Calcutta – and the Council agreed. But Imhoff left his wife and son behind. Hastings would visit them regularly till Maria sailed for Calcutta to join her husband in October 1771. His affair with Maria might have died a natural death, but for the news that was to change his whole life. He was appointed Governor of Bengal.

By February 1772, Hastings was installed in Council House, Calcutta, to begin the most glorious years of his career. But he also regularly visited his property in Alipore, near which the Imhoffs lived. It wasn’t long before the couple was once again supported by Hastings and all Calcutta was not only agog at the goings-on but also rife with rumours of bargains the Baron and Governor were trying to strike. Whatever the truth behind the rumours, Calcutta had no doubt about the relationship between the now-designated Governor-General, India’s first, and the fashionable Baroness whose quaint English was so charming.

When official news finally reached Calcutta in 1777 that the Baron, who had been summoned to England by the Company, had been granted a divorce in June 1775 on grounds of incompatibility and being “an abandoned conjugal mate”, Hastings had all Calcutta in a flap by marrying, on August 8, 1777, Anna Maria Appolonia Chapuset, the bride being given away by his former schoolmate and the then Chief Justice, Sir Elijah Impey. The Governor-General soon presented to Calcutta society, at a reception, Britain’s first First Lady of India, whom all Calcutta thereafter called his ‘Governess’. “Beloved Marian” not only held his heart in thrall, but also had a “fixed ascendancy over his mind”! To please Marian was to gain the favour of the Governor-General. But the expression of favour on several occasions bordered on the gross misuse of office.

Calcutta was humming with rumours about all this, but only behind closed doors. And there, behind closed doors, the rumours would have remained, but for the crusading zeal of a man who may be considered modern India’s first journalist, a wild Irishman seeking fame and fortune – James Augustus Hicky, the founder of India’s first newspaper, Hicky’s Bengal Gazette, in 1780. Hicky’s early stories, snide references to ‘the Great Romance’, made him no friend of Hastings. And Hicky stoked Hastings’ ire with more direct references to corruption and impropriety in the Government. The government versus Hicky battle is the story Andrew Otis tells in Hicky’s Bengal Gazette: The Untold Story of India’s First Newspaper. A pity that the roots of the enmity, the ‘Maid Marian’, Hastings romance, gets short shrift. Nevertheless, what Otis narrates is a fascinating tale about the beginnings of the politicians versus journalists divide.

* * *

After getting tired of several jobs in England, Hicky had decided to try his luck in India. He reached Calcutta in February 1773. His first job was as a surgeon, prescribing medicines, bleeding patients, and removing abscesses. Later, he borrowed money to begin a business, purchasing a small vessel to trade between Calcutta and Madras. Unfortunately the vessel and the cargo were badly damaged in rough weather during one voyage and Hicky was in deep trouble, unable to return the loan taken from the bankers. And on October 20,1776, he entered jail for the first time in his life. The bankers had seized everything he had; his ship, his house, even his furniture. Fortunately, Rs. 2,000/- he had given to a trusted friend, helped him put to good use the skills in printing that he had learned earlier during his peregrinating career. With it he bought types and hired carpenters to make a printing press, smuggling these into jail. He began working from there, printing handbills, advertisements, almanacs, documents for the Supreme Court and even insurance forms. Since prisoners had to pay for their own food and water, it was not uncommon for them to find ways to make money. After many long months, he scraped together a few hundred rupees, enough to order a set of printing supplies from England. He soon got rid of all his debts and with a lawyer getting him acquitted, he began a business that would improve his life.

While still in jail Hicky had got a contract, his first, with the Company, to print the Army’s requirements. He was the only printer in Calcutta at the time. Armed with this experience he sought and got the Army’s order for printing the new regulations, which, it was hoped, would set the Army’s code of conduct for years to come and prevent the corruption that was flourishing.

For Hicky it was a huge order. He borrowed money for the project, hired staff, and added equipment. But unfortunately the order was given to him without the knowledge of the Governor General and Hicky found himself in trouble. He began to think of other ways to make money. He felt that he could be much more than a job printer; someone who could provide society with a useful service by printing a newspaper.

Hicky began posting notices all over the city promising to revolutionise news reporting in India. While Indians traditionally got their news from friends and contacts, Europeans had been reliant on newspapers which came from Europe and America, arriving on ships many months after they had been published. He promised his newspaper would act as a community bulletin board, where everyone could post and reply to advertisements. His proposal came at a perfect time as news was in great demand in Calcutta because of the ongoing wars in three continents which had disrupted trade. Merchants needed to know which shipping routes were open and travelers needed to know when it was safe to sail. Hicky would provide this information. As the first journalist in India he would have a monopoly over news.

Hicky was, at the same time, aware of the dangers of printing a newspaper. In his early life in London’s printing industry he had seen journalists punished and jailed for what they published. He promised to avoid party politics and scandal that had doomed so many other journalists. In his proposal for his newspaper he promised “rigid adherence to Truth and Facts” and a commitment to not print anything that could “possibly convey the smallest offence to any single individual.”

Hicky’s Bengal Gazette, the first newspaper in Asia, came out on January 29, 1780. Hicky soon realised that his promise to stay away from politics would be harder to keep than it was to write.

(To be concluded next fortnight)

Dear MMM — Many thanks for this reportage. I browsed it rather late. We all knew about the famous dwell between Warren Hastings and Sir Elijah Impey near Belvedere in Alipore Calcutta. But certainly not in such authentic detail. You certainly deserve a PhD on digging out the incidences in uncertain days of early Colonial Period of British India. Like your Madras Musings one “Ajantrik” is dishing out from time to time a column named “Purano Kolkata” — in facebook . It would be nice if we join together and fish out many historically important events connecting Calcutta – Madras – Pondicherry ,– Bombay etc. in eventful days of our colonial past.As for example we know very little of native Indians movements between Madras and Calcutta. Before Swami Vivekananda’s Madras visit — we only get Poet Michael Madhusudan’s name for his ten years stay in Madras. I strongly believe Madars’s contribution in helping Madhu to unleash his poetic genius is epochal. Without the help of Madras Gazette to publish his first Poetic venture: Captive Lady — Madhu would never have arrived as a Great Poet at all. With best of regards….. nkm