Registered with the Registrar of Newspapers for India under R.N.I 53640/91

Vol. XXIX No. 19, January 15-31, 2020

Lost Landmarks of Chennai

– SRIRAM V

It was D. Krishnan, formerly of The Hindu, who first called me sometime in 2018 and asked if I knew that the Gordon Woodroffe building on First Line Beach/Rajaji Salai had been demolished. I said I had, for it was only some weeks prior to this that leading a heritage walk, I saw a gaping hole where the handsome edifice once stood. Krish asked me how I was so calm about it. There was a time when I would have raged against such acts of vandalism but I have long come to the conclusion that Chennai does not care and so one man’s laments are not going to make any difference. In the interests of my own health and longevity,

I prefer to turn the other way and document what is lost by way of this column. This way, at least future generations will know of what heritage we once had.

But then, let me get on with the elegy on the Gordon Woodroffe building. Somerset Playne’s Southern India is my go-to resource for much of the city’s early corporate history and sure enough, the book did not disappoint. And what’s more, it carries a picture of the building in all its glory in 1914. Gordon Woodroffe & Co (GWC for short), was, according to Playne, founded on the same site where the building stood, in 1868, thereby making for 150 years of corporate history when the structure was eventually brought down. In 1914, the partners were G.W.P. Woodroffe, W.A. Wigzam, Sir Hugh Stein Fraser and J.F. Simpson.

Like most British business houses of Madras of that time, GWC was in the business of export of raw materials and import of finished goods. This was a hugely profitable activity, its success dependent on keeping out any local development of industries and preventing Indians from getting into business. The company was a pillar of the British-dominated Madras Chamber of Commerce, and its Directors were routinely elected to the post of Chairman of that body. There was quite a bit of crossholding when it came to shares in other British business houses of the city. Sir Hugh was the brother of Sir Gordon Fraser of Best & Co, and a Director in that entity too. J.F. Simpson (later Sir James), was among the founding fathers of Assocham, the Association of Chambers of Commerce of India. He also served on the board of the Imperial Bank.

As per Playne’s note, GWC exported seeds, hides, skins and general produce and imported piece goods (essentially finished garments made of Manchester yarn spun from cotton sent out of the Americas and India, sold at throwaway prices in bulk and which killed the indigenous handloom industry), yarns, kerosene oil, metals and sugar. The export of palmyra was yet another profitable activity for which a cutting, drying and baling facility was set up at Colachel, employing ‘several hundred natives’. The palmyra was exported for the manufacture of brushes and made its way to London, Liverpool, Rotterdam, Antwerp, Havre, Hamburg and New York. Within the country, GWC had offices in Bheemunipatnam, Vishakapatnam, Pondicherry, Kakinada and Cuddalore.

The company also specialised in agency activity. It represented the Clan Line, which despatched two ships a month from Glasgow, Manchester and Liverpool, the Hansa Line which ran steamers to Antwerp, Middlesbrough and New York, and the Wells Line, which operated from Middlesbrough and London. There were, besides, a whole host of insurance companies that GWC represented in India, and it also managed tea and coffee estates.

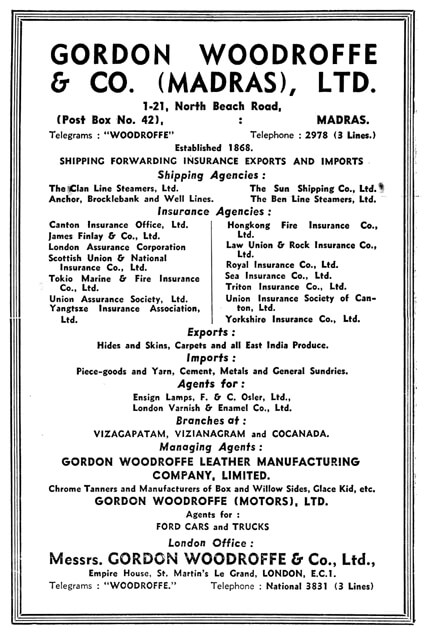

An advertisement in the Centenary volume of the Madras Chamber of Commerce, dating to 1936, shows not much had changed but there were some new product lines. GWC had formed Gordon Woodroffe (Motors) Limited to represent Ford cars and trucks and was also representing companies making lamps, varnishes and enamels. The most significant development was the formation of Gordon Woodroffe Leather Manufacturing Company Limited ‘chrome tanners and manufacturers of box and willow sides, glace kid, etc’.

Over time, the leather and the clearing and forwarding businesses of GWC came to occupy centerstage. The skin and hides facility spread over 100 acres in Pallavaram and employed almost 1,500 people. The company Indianised in the years following 1947 and in 1966 had its first Indian managing director – C.D. Gopinath, known also for his prowess in cricket. The shareholding, however, remained largely British, with 87 per cent being with expatriates. During his time, the company was a regular at all leather expos abroad and its products were much in demand. However, with successive legislations largely frowning on what were known as FERA companies, GWC found its scope somewhat restricted. Competition from Indian-run companies, always more dynamic when compared to the boxwallah entities did not help. But with Gopinath at the helm, the going was still good.

By 1964, Gordon Woodroffe London, which was the holding company, came into the hands of Eric Sosnow, a Polish refugee who began life as a journalist and later drifted into business. A graduate of the London School of Economics, he later became a major donor to the same institution. He soon began looking deeply into the Indian company’s affairs and suggested methods to improve the business, not all of which were strictly as per Indian law. Many of the remaining expats resisted this and left. Gopinath too quit in 1977, starting off his own business in shipping and making a great name for himself.

By the early 1980s, GWC was in the news – its huge landholdings had come to the attention of Manu Chhabria, the corporate raider, who acquired the company through another takeover of his – Shaw Wallace. By 1985, he was the darling of the media, regularly making the news through his endless string of acquisitions, most of which were old British companies with plenty of real estate.

An advertisement in the Centenary volume of the Madras Chamber of Commerce.

An advertisement in the Centenary volume of the Madras Chamber of Commerce.But by the 1990s, the Chhabria mystique had begun to unravel. There was a bitter fallout with his brother Kishore and the financial institutions had begun to complain about mismanagement and asset stripping. Most of Chhabria’s acquisitions became sick and GWC was no exception. Within a decade of its acquisition, the company’s sales fell by 40 percent. The brothers, with Kishore owing the bigger stake in GWC, slugged it out in Court. It did not help that Manu Chhabria moved out of India in 1995 fearing investigation and never came back, dying in Dubai in 2002. A court judgement said it all when it noted that Manu Chhabria had consistently defrauded the company and acted against its interests. By 2005, GWC was in the news for the sale of its assets. The Pallavaram space was knocked down for Rs. 300 crores by the Emaar Group of Dubai. The land in Maraimalai Nagar was acquired by The Hindu, which moved its printing facilities there.

From the time I began conducting heritage walks in the George Town area, this building of the GWC was more or less an empty shell. Keeping it company was the sloping-roofed tea shop next door, which going by Playne’s photo of 1914, was around even then! Both declined more or less together, the tea shop shutting down first and later collapsing, eventually becoming an empty plot. Now it is the turn of the GWC building to go. It is not certain as to who is the present owner and what is going to come up in the space.

What is ironic is that the High Court, in its order concerning heritage buildings had classified the GWC under category 2a – buildings possessing cultural, aesthetic and architectural merit which form an important part of the city’s heritage and contribute to the image and identity of the city. That judgement was rendered toothless by subsequent orders and the machinations of the bureaucracy-builder nexus. We are well on our way to becoming a city without image or identity.

I am interested in any detail re Hugh Fraser of best and Company (mentioned above) and his brother Sir Gordon Fraser who was – I think – the senior British Resident. They had a third brother, Alan Fraser, who was my grandfather and my father was born in Madras in 1920. I would also like more information, if possible, on Best and C.