Registered with the Registrar of Newspapers for India under R.N.I 53640/91

Vol. XXIX No. 4, June 1-15, 2019

Lost Landmarks of Chennai

Sriram V

When North Madras had a beach

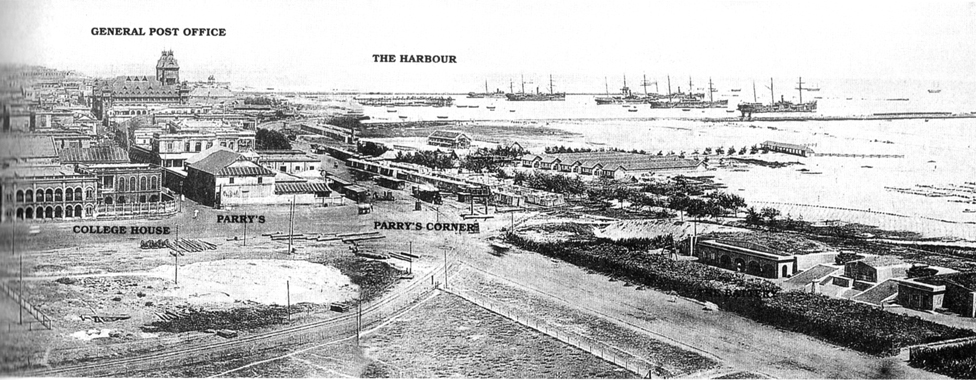

The Harbour, which was once North Beach.

To most city dwellers, the beach means the Marina. To some the term may also include the Elliots Beach, known now by the horrible name of Bessie, ostensibly because it abuts Besant Nagar. Then you have the Neelankarai Beach and several others. In the past, the Marina too had two distinct parts – Triplicane and San Thomé beaches. But before all of these was North Beach, which now is no longer in existence.

There are no records of North Beach – not one description of it exists. And at the same time, there are plenty, for most writings prior to 1900 or so that describe a beach in the city are actually referring to North Beach alone. And it is from those sources that we need to recreate its story.

The first clue comes from the name North Beach Road. Today known as Rajaji Salai, it also was referred to as First Line Beach – giving you an idea – this was the first road to the west of the beach and extended from Fort St. George all the way to Royapuram and beyond. Diametrically opposite ran South Beach Road, now Kamaraj Salai, and this connected the Fort to San Thomé. In comparison to the latter, which ran along a narrow strip of sand, it was the former that presented a fine prospect of a beach with the sea beyond. Today the situation has completely reversed. We, who are familiar with crowds thronging the Marina on a summer’s evening, will find it hard to believe that it was to North Beach much of the city went in olden times. Most of the traverse thoroughfares of George Town such as Errabalu Chetty and Anna Pillai Streets actually connected to it.

North Beach then, as mentioned earlier, ran parallel to First Line Beach, from the Fort to Royapuram. “This is the business part of the town, and contains the banks, customs house, the High Court, and all the mercantile offices. Many of the latter are handsome structures and fringe the beach” – thus enthuses the Imperial Gazetteer of 1885. There was of course the opposing view – “Not one of these can be compared to Esplanade Mansion of Calcutta,” wrote Mylai Ko Pattabhirama Mudaliar in his Vishnu Sthala Manjari (1908-1913).

The High Court as mentioned in the Gazetteer is not the present building, which was completed in 1892. It refers to Bentinck’s Building, which stood on First Line Beach and on whose site was built Singaravelar Maligai, the office of the Collector of Chennai. This building was home to the Supreme Court of Madras between 1817 and 1862 and thereafter the premises of the High Court till 1892. This led to North Beach also being referred to as High Court Beach. Most lawyers walked on it of an evening, after their arguments in Court.

The best days of North Beach were between 1799 and 1875. It was in the former year that Edward, the 2nd Lord Clive famously declared Fort St. George to be out of bounds for mercantile activities outside the purview of the East India Company. To encourage the free merchants in the Fort to leave, he had the office of customs shifted from just outside the Fort’s sea gate to a place further north, and housed it in a disused granary. The road leading to it from the Fort became First Line Beach and Customs House stands on the same location as where the granary once was. With the Sea Customer moving from the Fort, ships, which had dropped anchor two miles in the sea just east of the Fort, moved northwards too. They began to stop opposite the Customs Office and so the merchants had to move. The first to do so was Thomas Parry. He bought land and building at this desolate spot in 1803. The property, once the site of Lally’s Battery and from where the French had bombarded Madras, albeit unsuccessfully in 1758, belonged to a Begum of Arcot and Parry acquired it to build his company’s headquarters. The firm Parry & Co, now owned by the Murugappa Group, still functions from the same place though the present building dates to 1939.

The spot was not exactly safe – the sea was known to lap Parry’s walls during certain high tides. To protect the inner city came up the great Madras Bulwark, a wall designed by Thomas Fiott de Havilland. It ran along much of First Line Beach and the present RBI subway. With Parry setting the example others followed. Soon North Beach Road was no longer desolate and boasted of among other institutions, the city’s best-read newspaper – The Madras Mail, the General Post Office and the Railway Station, which came up in Royapuram.

The harbour was yet to be built and ferrying of passengers and cargo, to and from the ships was by means of catamarans – native rafts. The head boatman or Sarhang was a key figure and Narayana Syrang and Jaffer Syrang Streets near North Beach commemorate at least two of them. Some of the biggest cargoes for the times arrived here – the statues of Lord Cornwallis and Sir Thomas Munro, and also the first four railway locomotives. A public holiday was declared to witness the unloading of the latter. The arrival of many sailors also meant other services – Vodacaul Street, the city’s busiest red-light area, was just west of North Beach.

“The north beach, with the flags surmounting several of the mercantile offices, and the dense crowds on each side, presented a very picturesque effect,” ran a description of the farewell accorded to the Duke of Edinburgh, one of Queen Victoria’s numerous children, when he visited the city between March 22nd and 27th, 1870.

In 1875 began work on the harbour for Madras, to replace the screw pier of 1856, which extended all the way from North Beach to Madras Roads, the spot in the sea where the ships halted. With that, North Beach’s days were numbered. As the screw pier gave way for a bigger and better organised harbour, land was needed for expansion. North Beach was the natural choice. The Government hummed and hawed but the Port Trust was insistent as were commercial interests in the city led by the Madras Chamber of Commerce and the Madras Trades Association. By the early 1900s, almost all of North Beach had been ceded to the harbour, with one proviso – no permanent construction was to come up on it. This was duly honoured. But oil tankers were put up here for bringing in petroleum and kerosene by sea. These were the first targets when the German ship Emden shelled Madras in 1914. North Beach and much of what lay beyond were the worst affected.

“Went to the beach,” wrote the diarist N.D. Varadachariar in 1918. He was all of 15 then. “I didn’t like the crowded beach at all. I hate human habitation, especially when ‘fashionable females’ are present.” Later his liking for the North Beach improved and there are accounts of outings there, in the company of his close friend, T.T. Krishnamachari. On December 1, 1937 he notes that the “entire George Town is en fete owing to the grounding of the ship Clan Morrison. What fun is there in a ship running into sand I cannot understand. What a psychology!” This happened at the northern extreme of North Beach, at a place called Royapuram Beach, which is where residents of that locality went to enjoy the sea and the breeze of an evening.

By the 1940s, North Beach had vanished almost fully. Royapuram lost its beach to a wall that was constructed all along the eastern front, barring access except by a narrow lane to the water. The construction of the harbour gave rise to the phenomenon of littoral drift, which in turn led to a broad beach towards the South. That was given the name Marina by Governor ME Grant Duff. We know the rest of the story.