Registered with the Registrar of Newspapers for India under R.N.I 53640/91

Vol. XXXI No. 1, April 16-30, 2021

Trade in Madras, via the sea

Urging me to write the history of Madras in Tamil

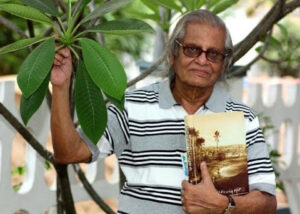

Sometime in 2003, once when I casually mentioned to Mr. Muthiah about my book in Tamil getting an award from the Tamil Nadu Government, in the category of history, he asked as to why I should not try to write the history of Madras in Tamil. That gave me the urge to write and late in 2005, when I had completed my draft on the Tamil book Madrasapattinam, I took the manuscript to Mr. Muthiah, who was clearing my doubts about the history of the city when I was writing. I told him that it would be nice if he could write a foreword for the same. He instantly agreed with one condition that he would do it in English and I should render it in Tamil.

In a week he called me to collect the foreword. He said he liked the work a lot and had mentioned in the foreword, “. . .I really know of no one who covered so long a period of Madras history as comprehensively as Narasiah has done in this book.” And ended with a statement, “. . .May I hope they now bring out an English edition as well?” He asked me to contact Mr. V. Ramnarayan for an English publishing house.

That I did and that is how the English version Madras – Tracing the growth of the City since 1639 came to be.

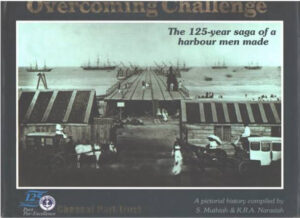

Later when we wrote Overcoming Challenges – The 125-year saga of a harbor men made my research into shipping while writing about Madras came handy.

– K.R.A. Narasiah

At the start of the 18th Century, Madras began losing importance in proportion to gaining of the same by Bombay and Calcutta. This was mainly due to the latter cities’ superiority in harbour facilities. They both had well developed hinterlands.

Rudyard Kipling sang on the condition of Madras in his famous lines:

“Clive kissed me on the mouth and eyes and brow

Wonderful kisses, so that I became

Crowned above Queens; a withered beldame now,

Brooding on ancient fame”

Madras was neglected with the result that trade began to decline. The traders began to press for a protected harbour. While Calcutta harbour was located on the banks of the Hooghly and Bombay harbour was in the calm waters between islands, the Madras seashore faced the open sea with all its furies directly hitting the shore. It was a great experience to see a ship arrive and disembarkation take place in the surf. The arrival caused great excitement. Everybody from the Town would throng the beach to watch the ship anchor in Madras Roads, a mile or more from the Fort. In front of the ship was nothing but angry surf and a narrow strip of beach that could be reached only by local rowboats called masulas. The journey to shore and back was fraught with danger and made more miserable by the unreasonable demands of the boatmen.

The longest serving Chairman of Madras Port, G.G. Armstrong, writing in 1939 of those early days says:’The present expanse of sand in front of the Fort was not there; in stormy weather the sea came right into the Fort moat, and at one time threatened to undermine the foundations to such an extent that the Company seriously considered abandoning the place. But in stormy weather there was no trade; the ships avoided monsoon months. In fine weather they lay at anchor outside the surf and the goods and passengers were all landed by masula boats through the surf on to the beach. Many descriptions have come down to us of landing at Madras in these boats, how the boatmen waited for a big wave, came in on the crest of it till it was spent, paddled hard to get past the breaking place of the next wave so as to be carried by it right upto the beach. And as they waited outside the surf for a good wave they bargained with their passengers; ‘their luggage was so heavy they must give extra pay’; and the passenger, thinking his last hour had come, usually paid. If he did not, or if his luggage looked valuable, a box or two usually fell out into the surf, whence the boatmen salved it at their leisure. Most of the profits were made out of passengers; possibly the Company’s goods were more carefully treated. But there was nowhere to put them; they were piled anyhow on the sand in front of the Sea Gate at the Fort, where the road now runs, until they could be carried in through the Sea Gate past the Sea Customer whom we now call the Collector of Customs and stored in the Company’s godowns in the Fort. In the same way were treated the goods for export to England; cloths and muslins were bought from local merchants, or made by the Company’s weavers in their newly established suburb of Chintadaripet. They were washed by the Company’s washermen at first close to the Fort and, later, as things became safer, further away at Washermanpet. They were sorted by the Company’s officers and kept in the Company’s godowns in the Fort till one of their ships came in; then the goods were carried through the Sea Gate to the beach and taken by masula boat through the surf to the ship.’

The chief items of trade through what passed for a port in Madras’s early days were paintings (chintz on which coloured designs were imprinted by wooden blocks or traced by hand) and Morres (a plain blue cotton cloth). Madras dyes were held in high respect. A Spanish priest in 1670 wrote that in Madras, ’the conveniency of buying clothes is great’.

Similarly, the quality of ropes (cordage) manufactured in Madras region was acknowledged throughout the East. As early as 1726, the Chief Gunner at Madras begged the Government to prohibit the import of coir cables because ’these cables sold to ships in this place, if damaged or not well made, may pass for Madras Cables, and bring an ill repute on the cable and cordage of this place, which has hitherto the repute of laying cables the best of any port in India.’

In 1791, the piece goods exports from Madras included ’Allejars, Betellers, Callawa Pores, Chintzes of all sorts, Ginghams, Izarees, Long-cloth, Morrees, Salempores and Sastra cundies.’ Chintzes and ‘morrees’ were much in demand.

Between 1797 and 1810 there was a nine-fold increase in production of cotton textiles in England, yet, demand for calicoes and muslins from the Coramandal increased. ’Nothing else,’ wrote a dowager of the realm in1797, ‘is worn in gown by any rank of people…I can get them cheaper here, but great choice there is, very beautiful and REAL India.’ ‘REAL’ India’s reputation was based as much on the quality of cotton as the Madras dyes which, it was said, ‘never run and scarcely fade’.

…The earliest regulation, which legalized the levy of sea customs duties in the Presidency, was the Madras Regulation I of 1802 (Section 2). A consolidated enactment was passed the next year. Such duties however, appear to have been collected in Madras without legal enactment for many years before, the earliest record in the Madras Sea Custom House dating to 1786.

By the end of the 18th Century, the Company had established its control and authority over a great part of peninsular India – from the Northern Cicars (southern Orissa) to Cape Comorin and upto ‘Canara’ (now Uttar Kannad). The beginning of the 19th Century , then, was a turning point in the history of the Company and of South India. Trade may have been the professed objective of the Company, but with territorial expansion, its officials were getting more involved in politics and administration. The demand for the end of the Company’s monopoly and the cry for ‘Free Trade’ in India grew, as a consequence.

By the Act of 1813, the East India Company’s trade monopoly was confined only to China; the right of trade in India was thrown open to all British subjects. When the Charter came up for renewal in 1833, even the exclusive right of trade of the Company with China was done away with. By the India Act of 1833, any British subject could freely sell his products and buy primary commodities in India. The modern age of Madras Commerce had begun…

Extracts from the book: Overcoming Challenge, The 125-year saga of a harbour men made.