Registered with the Registrar of Newspapers for India under R.N.I 53640/91

Vol. XXXII No. 13, October 16-31, 2022

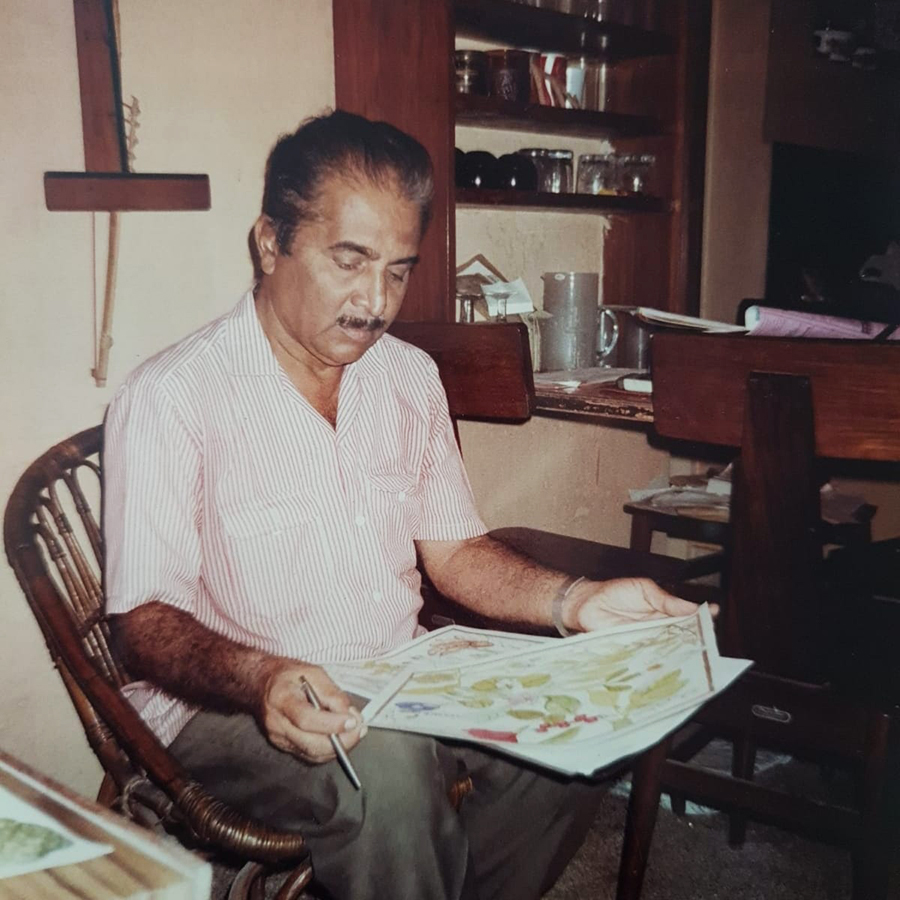

Remembering OTR

-- by Shobha Menon

In 1994, the Spring Bulletin of the Hunt Institute of Botanical Documentation, Carnegie Mellon University, Pittsburgh, (Vol. 9 No. 1) recorded that collections from Madras were ‘lacking in botanical art, except for the prodigious private collection of artist O.T. Ravindran, nurseryman, landscape designer, ecologist, journalist, and interesting personality.’ They were praising an extraordinary man with an inordinate and legendary passion for plants and flowers, Ravindran Oyitty Thavorath (1934 -2006), popularly known as ‘OTR’ or OT! One of the top 50 flora painters of the world, he was also one of the few commissioned Indian artists who contributed immensely to scientific flora records during the British Raj, particularly after the founding of the School of Arts and Crafts in then Madras.

O.T. Ravindran – OT Ravindran Foundation.

O.T. Ravindran – OT Ravindran Foundation.I first met him in 2004 in his workspace, the top floor of a quaint garden house (now replaced with a high rise), in tree-lined Nandanam extension of Chennai. Beautiful sketches lay around on a large work desk covered with piles of paper, books and art material – aging paint palettes, glass jars, faded plastic mugs holding up paintbrushes, and tubes and slabs of paint. And I was intrigued by the way he pottered around delicately without disturbing the surrounding profusion of paintings and plants!

I had heard of OT’s worldwide recognition, which included winning the Grenfell medal five times consecutively at the Royal Horticultural Society, London, and being featured in the database of scientific illustrators – 1450 to 1950 and the Hunt Botanical Library, Carnegie Institute of Technology, 1999! His friend and writer Theodore Baskaran, remembers, “OT worried little for money or fame and was passionate only about his plants, a green environment and the rains”. It was Baskaran who introduced me to OTR.

OT’s painting of a banyan tree, was part of a natural series released by the Department of Posts, India. On 12th October 1991, six multicoloured stamps (of denomination – Rs. 1.00, 2.50, 3.00, 4.00, 5.00, and 6.50) that represented his botanical paintings were released. On 9th October 1993, four more stamps (of denomination – Rs. 1.00, 6.00, 8.00, and 1.100) were released. The total number of stamps (by India Security Press) printed of OTR was one million that year!

His 15 paintings of wildflowers that belonged to Pacific Northwest region of America, were widely commended and he revelled in their close relation to Indian counterparts. His painting collections – techniques included botanical ink drawing, wash, and watercolour – were presented to Lady Bird Johnson’s (widow of the former U.S. President, Lyndon B. Johnson) Wildflowers Research Center in Austin, Texas. “O.T. Ravindran might do for the weeds and wildflowers of India what James Audubon did for the birds of America”, said an American columnist in 1984! But that was not to be. He was more recognised in the West than within India, where botanical art itself was not much understood.

His brusque manner and righteous indignation at apathy toward the environment within the community made him almost a recluse. On one occasion he shared with me how a resident from the neighbourhood wanted to cut down a magnificent tree at the street corner for some flimsy reason. “And I decided it was time I went out with my trusted shotgun”, OT smiled wickedly. I can still see that tree stand graciously tall, a decade later!

That rainwater added more life and natural colour to the delicate wild floral beings that he captured on paper, was a particularly memorable lesson from OT! He showed me around his rudimentary harvesting plans – pipes all around the terrace siphoning water into tanks and large tubs, excess water draining into a well in the compound. And along his window sills, bottles, recycled jars, mugs of all shapes and sizes collected rain water too! “That means I have another six months’ supply of water for use in the house, for growing my little saplings and also a year’s supply for watercolour painting”, he revelled. “He would peer over a plant or flower over different times of the day or seasons to mirror their texture and colour” says Baskaran. Alongside working on watercolor portraits of South Indian orchids, he also cultivated them.

His campaign for trees in Madras, and ‘the right kinds of trees to plant in appropriate locations’, came at a time when the concept was largely unclear. A 1985 bulletin of the Madras Naturalists’ Society, recorded how, on 14th April in Guindy National Park he had provided his insights on choosing the right species of Avenue trees, and plantation of ‘no dive trees’ that ‘can withstand nature’s harshness, so that the extreme natural calamities such as cyclone cannot damage them’. He also founded the Environmental Society of Madras in 1989.

On another visit, as I poured out my anguish at the insensitive tree abuse that went on all around, he narrated how in the 70s a famous Pizza company had nailed all avenue trees alongside a city road for their ‘Buy One, Get One’ offer. And he had immediately recorded a complaint with the CEO. A suave company rep had come to him, saying ‘it didn’t harm the trees anyway’. And how he replied, “How about my nailing you on your back with a board precisely as you have done to the trees, and then you let me know if it’s okay!” The banners were promptly removed from the trees, the next day itself! Eyes twinkling, he then handed over to me a copy of his short story collection, ‘Middles’, penned in his typical sardonic, tongue in cheek style. “I like it when people call me a ‘nutcase’!”, he smiled.

One lazy afternoon in his garden, as I went into raptures over an Indian laburnum sapling that I wished to plant in a children’s park near my home, he said sternly, “If you will plant and care and raise it yourself, then and only then I will give you this little one. Otherwise NO”. We often discussed his custom-made designs for bird feeders and bird baths to attract more birds into home gardens and parks, and he was gentle and patient in answering all my questions. He also relished the traditional ‘mallu’ eats that I shared, an occasional nendrapazham puzhungiyathu (boiled nendran banana), and avil nanchadhu (jaggery sweetened, flattened rice delicacy). Maybe it reminded him of his childhood in verdant Kannur!

Sharing his anguish at bureaucratic hassles and lack of understanding of his botanical work in India, he had rued, “I intend to give them all away to the Smithsonian. They will be safer there!” Several of his paintings still continue in the collection of the Smithsonian in the U.S. and the Kew Gardens, U.K.

Sadly, and soon after, he began to be troubled by a debilitating health concern. On a chance visit, I found him in a room at the ground floor, very unusually for him. “I am sorry I don’t feel well and I’m not able to answer any questions”, he said, with a tired look. OTR passed on a few months later, in February 2006, at the age of 72.

OT was truly a giant among men, and gentle as could be. He is deeply missed by his many admirers. And I feel deeply privileged to have known this extraordinary personality and his ethereal love for plants.

I had Chance to work with him few months. I visited his art exhibition in Chennai at Hotel Park Sheraton. His love to plants is highly commendable.