Registered with the Registrar of Newspapers for India under R.N.I 53640/91

Vol. XXXII No. 5, June 16-30, 2022

Lost Landmarks of Chennai

Madras in 1759 – I

A chance search for some material on the Elambore river landed me on this account of Madras in 1759. Published in the Grand Gazetter (sic) of Exeter that year, it gives a fascinating account of White Town and Black Town. The first part reproduced here details Fort St. George shortly after the French had left and before the constructions of Patrick Ross and others had begun. We find that that the Capuchin Church of St. Andrews was still standing. There are descriptions of houses, the army, the security arrangements and above all the way private trade flourished. The spellings have all been corrected for convenient reading. Square brackets are notes provided in the original text, round brackets have been added by me.

– Sriram V

The White Town

Fort Saint George or Madraspatan [which in the Indian language signifies the town of Madras] on the coast of Coromandel, lies about 9 leagues south of Paliacatte (Pulicat), 2 degrees north of Saint Thomas (San Thome), 6 of Cabalan (Kovalam), 23 from Pondicherry and near 4,800 miles east of London according to some, but Templeman calls it 3,790 leagues east of London, and the sun rises and sets here 6 hours sooner than with us generally at 6:00 morning and 6.00 evening. The East India company were put in possession of it by one of the Pagan Princes nearly about 130 years ago, and had it ratified by the King of Golconda, to whom they pay 7,000 pagodas [worth about 9 shillings apiece] per annum for the royalties and customs but they gain four times the sum by them to the amount of 30,000 pistoles (Spanish gold coin and worth at that time around 18 shillings) at least (this gives us an idea as to how profitable the EIC was). It is a place of the utmost importance to them for its strength, wealth, and the great annual returns it makes in calicoes and muslins.

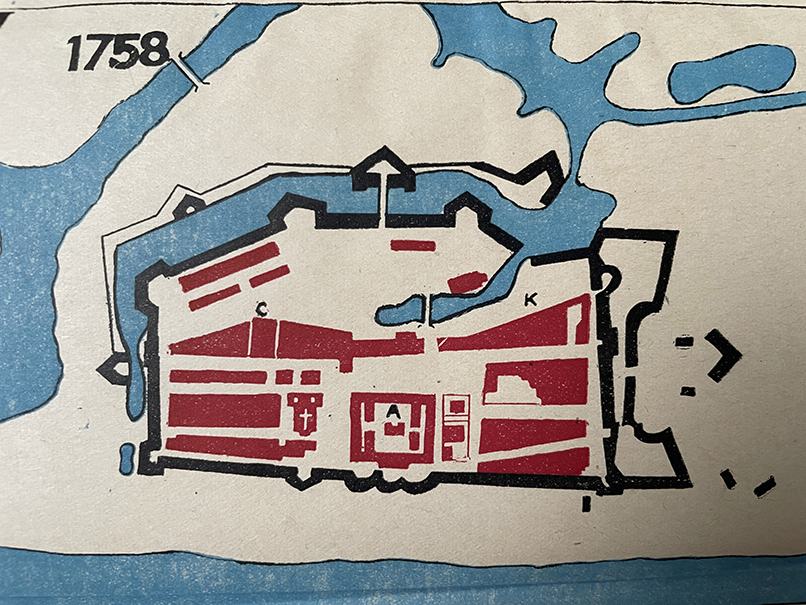

Fort St. George in 1758, from Lt. Col D.M. Reid’s The Story of Fort St George. A is Fort House, G is Clive’s House and K King’s Barracks.

Fort St. George in 1758, from Lt. Col D.M. Reid’s The Story of Fort St George. A is Fort House, G is Clive’s House and K King’s Barracks.The governor of it is also so of all the settlements on this coast and the West Coast of Sumatra; he that presides at Bencoolen being but its deputy governor there. The governor is captain of the first company of soldiers as the second in council is of the next. He lives in great pomp and state and his judges pass sentence of death on any but the subjects of Great Britain. He and his council inflict any corporal punishments short of life and member, on such Europeans as are in the service, and dispose of all places. They had greater power once but now execute no Europeans but pirates. He has yet authority to send prisoners to the Cork House, a hot dungeon under the town wall where they are allowed but rice and water, which is such a stove that it is certain, though not so quick, death as the halter (death by hanging), and the officers are sometimes by him suffered to hold courts martial and inflict punishment on the soldiers. He has but 200 pounds a year salary and 100 pounds a year gratuity; for so that the fortune they generally make is by trading (private trade by which most early Governors of Madras became rich). His constant guard is three or four blacks, besides 1,500 ready on summons. When abroad on extraordinary occasions he is attended by the fifes, drums, trumpets, and two union flags, his counsel and factors on horseback, and their ladies in palanquin. On ordinary he has 60 or 80 peons [of whom 200 are kept in pay] besides his English guards, with loud rough music of that country. 50 or 60 armed blacks run before him and the cleverest of the European soldiers run by his palanquin armed with blunderbusses. He is also attended by a runner. Train of servants come up particularly two, called dubashes, to fan him and drive away the flies; and he is in all respects as great as the rajahs of the country. 200 soldiers drawn up in a line from the inner Fort to the church door guard him to it. Yet indeed this state is infinitely short of the Dutch governors of Batavia. The chief of his counsellors has 100 pounds a year. The two essay masters of the mint, one judge and two ministers, have each the same and a house. But though the said persons are not suffered to trade openly, yet they lay up to 1000 pounds and the Judge Advocate with his small salary makes as good a figure as a Lord Chief Justice in England. The Portuguese, who fled here for protection when the Moors drove them from Saint Thomas are obliged to raise a company or two of trained bands, on occasion.

Beef, pork, poultry, venison, fish, are much cheaper than Europe. Wildfowl are so plenteous that three teal, or twenty green plovers may be bought for 3 dimes. But wine and beer are sold at very high rates so that punch is the common drink of Europeans. Linen is so cheap that a private soldier can afford a clean shirt daily. Every one of these has his boy to wait on him; for their Indian parents let them serve the English for a trifle, to learn the language.

The whole town is divided into two, though some make of them three, towns which is the English or White Town and the black city on the north side of it called by the Moors Madrass or Chinnapattan. But then on the south side of the White Town is a little suburb called Maqua where the black water men and fishers live and beyond that is kept an out guard of blacks to give intelligence to the Fort. In the White Town stands the citadel, or a Fort having two gates, west where is the main guard, east towards the sea. It is defended by four large bastions who’s north and south points are 108 yards from one another and those of the east and west 100. The keys are every night delivered to the governor, whose lodging, and apartments for his servants, etc, take up 1/3rd of it. The outer Fort has batteries, half-moons, and flanks, mounted with 150 guns and three guard towers besides 32 guns and eight field pieces on the outworks. The walls both of town and forts are built of ironstone (laterite), so called as being of the colour of wrought iron, and very rough on the outside like a honeycomb.

The White Town is about a quarter mile long, not half so broad. There are three handsome streets to the south and the like north of the Fort whose houses [about 120] are of brick with flat roofs covered with a plaster formed of seashells, upon which no rain can penetrate; and being secured with battlements they take air on them morning and evening. The walls of some are very thick and the rooms lofty, and what’s peculiar to this country, the upper floors are laid with bricks. They are neat and stand generally pretty close to the streets without gardens or large courts but they have Italian porticos and row of trees before them. There is a barrack over against the west gate of the Fort where the soldiers off guard are obliged to lodge, when they send a corporal and two men every hour of night to patrol. North side is an hospital for the sick, who if soldiers, receive their pay, but if sailors, bear the charges of their own physick, and allow one shilling a day for provisions at the barracks. Other end is the mint, where is coined gold and silver. An English church, Saint Mary’s, stands on the north side of the Fort, a large arched pile, with fine carved work, and an organ. It is floored with black and white marble and is an elegant, lightsome structure, the windows large, not glazed, to admit cooling breezes. There is also a church for Roman Catholics (the Capuchin church of St Andrews which was later demolished). But the governor superintendents both churches. Other public buildings are the town house; under which is a prison for debtors; a free school with its public library; a college, formerly an hospital. There are other schools for different nations. Elambore river runs close by the buildings on the town’s west side where is no wall and only a large battery of guns on the river which commands the plain below it. East side a high stone wall though slight, appears grand to shipping in the road. It little needs being stronger, the sea, though it comes up to the town, being so shallow, that no large ships can ride within a mile of it. The town’s north and south ends are defended with thick stone walls; but they are arched in and hollow within and may scarce hold out to one day’s battery.