Registered with the Registrar of Newspapers for India under R.N.I 53640/91

Vol. XXVI No. 16, December 1-15, 2016

Rambling in West Mambalam … with Janaki Venkataraman

Strait-laced, conservative, middle class

It is a day like any other in a street like any other in West Mambalam. In the lane close to Srinivasa Theatre (one of Chennai’s oldest cinema theatres), the houses are packed closely together. They are functional, rather ugly houses, stacked side by side and it is -obvious no one cares much for architectural aesthetics in this part of town.

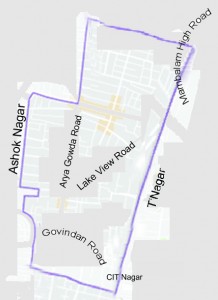

The Kashi Viswanathar Temple with West Mambalam surrounding it. (Photo: S. Anwar.)

The Kashi Viswanathar Temple with West Mambalam surrounding it. (Photo: S. Anwar.)After two days of wandering up and down these dusty streets (this is not really difficult, as West Mambalam is bisected by only two main roads, Lake View Road and Arya Gowda Road and all the streets lead off these two roads) I have concluded that West Mambalam is the most colourless area in Chennai.

It wasn’t like this a long time ago, when there was a huge grove of vilva trees here. So many vilva trees that the place came to be known as Maha Vilva Ambalam –the place of grand vilva trees, dear to Shiva. The name slowly changed to Maavilvam and, later, Mam-balam. You don’t see the vilva trees any more, of course, save the one in the 17th Century temple of Kashi Viswanathar on Easwaran Kovil Street. There was also a lake here, the Long Tank, that the British drained out in 1923. There were paddy fields where Srinivasa Theatre now is and Mambalam had all the scenic beauty of a village. It was then a part of Chingleput District and became a part of Chennai only in 1946.

Mambalam’s urbanisation started by default in 1911 when the government constructed a railway station there, as a stop on the Madras-Kanchipuram line. Until 1923, the Long Tank was considered the western limit of the city. When the Corporation of Madras decided to push city limits further, the Zamindar of Mambalam was happy to hand over the area to it. So it was in this direction that the city limits were extended. The Corporation drained the Long Tank to make more spaces for houses and commercial enterprise (a habit that has been -diligently and calamitously -followed by successive governments). The southern portion of the area was developed as a commercial centre and named Theagaroya Nagar. Divided by the railway line, the two portions of Mambalam acquired their separate initials – T. Nagar and W. Mambalam – and identities. Another reason for Mambalam acquiring its initial is said to be that it was also called Mylai Merku Ambalam, the place west of Mylapore. Then it changed to Mel Ambalam and finally West Mambalam. The areas surrounding Arya Gowda Road were later acquired from H.B. Ari Gowder, a Badaga leader and politician who owned much of the land here.

West Mambalam, perhaps because much of it was built over a drained lake, had some serious sanitation and drainage issues back then. The Mam-balam mosquito was a dreaded icon and the prevalence of filariasis was rampant in the area once. Those issues were later resolved and, since the 1960s, West Mambalam has grown into a middle class residential neighbourhood.

As I was saying, the place is colourless. It has none of the gaiety or buzz of Mylapore; nor the subtlety or sophistication of residential neighbourhoods in Nungambakkam, Egmore and the like; it certainly doesn’t have the rowdy, devil-may-care attitude of Tiruvottriyur or Pudupet; why, it does not in the least resemble even its counterpart across the railway tracks, T.Nagar, with its gaudy, hyper-active persona. Ask anyone in the rest of Chennai and they’ll say, “West Mambalam? What’s there? It’s a retirement community for super-annuated middle class Brahmins. Dull with a capital D!”

In my own wanderings, I could not sight a single high-end boutique, mall, theatre, or restaurant. Girls walking by were dressed either in sarees or demure salwar kameezes (the dupatta modestly draped across the chest), never in pants or short skirts; pigtails were common, cut hair hardly ever; the nine-yard madisar was sighted pretty frequently; if the men were not dressed in nondescript pants and bush shirts, they were definitely in veshti and anga-vastram; caste marks were worn, not defiantly but as a matter of course.

The only landmarks in the area are the Public Health Centre, a hospital run as a charity on Lake View Road and Ayodhya Mandapam, on Arya Gowda Road, a meeting place for pious Hindus (read Brahmins mostly) to chant mantra-s and listen to religious discourses and Carnatic kutcheri-s. No matter which way you looked at it, West Mambalam’s reputation for being the home of a strait-laced, conservative, middle class community, seemed solid. Why should anyone want to explore it?