Registered with the Registrar of Newspapers for India under R.N.I 53640/91

Vol. XXVI No. 24, April 1-15, 2017

The Madras Helix

by V. Vijaysree

The double helix is, perhaps, one of the most iconic structures from the world of science. The DNA, with its intertwined spiral shape, is the molecule of heredity. Decoding its structure and understanding its function in the cell was a big scientific breakthrough in the 1950s.

GNR, his wife Rajam and Dorothy Hodgkin.

GNR, his wife Rajam and Dorothy Hodgkin.

Not far from the banks of the River Cooum, in the heart of a national research institute, there is an auditorium called Triple Helix. Does this name have a basis in fact? Or it a case of taking poetic license with a well-known symbol? Not at all, as it turns out.

The name Triple Helix points to a David and Goliath story from the rarified realms of research. The plot involves a puzzle in molecular biology; the cast spans continents. A scientist in Triplicane is pitted against celebrated researchers – from labs at the University of Cambridge, the King’s College in London, and Caltech among others. This elite group of Goliaths includes the discoverers of the DNA structure.

The David in the story is Gopalasamudram Narayana Ramachandran, or, simply GNR.

The year is 1952. GNR, who is barely thirty, had just been tapped to head the Department of Physics at the University of Madras. As a graduate student, he had worked in the field of optics under C.V. Raman at the Indian Institute of Science (IISc). In England, he had worked for two years in the laboratory of Sir Lawrence Bragg, discoverer of X-Ray diffraction. This was the technique used to decipher the structures of biomolecules like the DNA and proteins.

Now GNR had a lab of his own. He was looking for a worthy problem to solve. The young scientist had decided that studying biomolecules would be the theme for the lab, but he didn’t know where to begin.

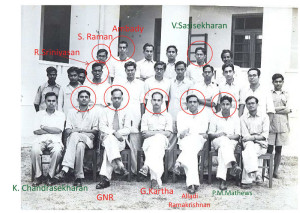

Group photo of 1955 with GNR seen with a tie.

Group photo of 1955 with GNR seen with a tie.

Right around then, a former colleague from England, the renowned crystallographer J.D. Bernal, was visiting Madras. During a casual conversation, he tells GNR that various research groups have proposed the structure of collagen — the most abundant protein in animals — but no one has hit the mark yet. Structure-wise, it seemed knottier than the DNA.

Collagen, present in the connective tissue of several species in the animal kingdom, gives strength and form to these creatures, humans included. Understanding the three-dimensional shape of this protein was important.

GNR had, at last, found direction.

First things first, GNR had to find a source of collagen. The shark fin collagen from the biochemistry lab next door on campus didn’t yield very good X Ray images. Good quality pictures, however, would be essential to unravelling the collagen structure.

It occurred to him: leather too is largely collagen. Not far from Triplicane, a new research institute had taken shape in Adyar — the Central Leather Research Institute (CLRI). He would pay it a visit.

Kangaroo Tail Tendon and Beef Achilles Tendon — these were choices in GNR’s mind as he made his way to Adyar. The Director of CLRI, Y. Nayudamma, turned out to be a kindred soul, happy to help a fellow scientist. The beef sample was easy to obtain locally, of course. But if kangaroo collagen was going to yield the best diffraction images — as was reported in literature — then, why, he would get samples from Australia, the Director promised. Before long GNR got purified marsupial collagen to work with.

Within two years, GNR and his group published the structure of collagen in the August 7, 1954 issue of the journal Nature. The authors suggested that the protein has the form of a triple helix — three distinct chains coiling upon themselves. This was a highly original insight.

Suddenly, top-notch molecular biologists in Cambridge, California, and elsewhere started paying attention to the work of the ‘Madras Group’. Among themselves, they started referring to the triple helical model as the Madras Helix.

So, how did GNR hit upon this triple helical structure? The scientist has said that astronomy gave him inspiration for the ‘coiled-coil’ model. Think of the night sky: the rotating Moon, which also revolves around Earth, always presents the same side to Earth. Similarly, in collagen, a chain of molecules (the amino acid called glycine) always faces the centre of the triple helix.

More simply: the collagen has three helices, “braided in the manner of the pigtail of a long-haired maiden from Madras,” as The Hindu’s science columnist D. Balasubramanian put it. Perhaps, GNR was subliminally inspired by his beloved wife Rajam’s everyday coiffure just as much as he was inspired by distant celestial bodies.

For a variety of reasons, GNR did not get immediate recognition for his insight into the structure of collagen. Undeterred, he took the criticism aimed at the Madras Helix and worked to find the underlying principles which determine what shapes protein chains can and cannot take.

By doing this, he came up with the very grammar of protein folding. To this day, the Ramachandran Plot (or map), is used to validate protein structures of ever-increasing complexity.

Like the Raman Effect, Heisenberg’s Uncertainty Principle, or Einstein’s Theory of Relativity, the Ramachandran Plot has made the scientist behind it memorable. Applying laws of physics to biological phenomena is now a new field called biophysics.

GNR is not a mere footnote in the literature of collagen structure.

During his tenure, he made the University of Madras a place of interest to leading structural biologists. Back in the 1960s, he organised two international symposia in Madras, one in the winter of 1963 and the other in the winter of 1967. Nobel laureates were among the attendees.

After close to two decades in Madras, GNR returned to IISc in Bangalore to set up the Molecular Biophysics Unit. The division he headed at Triplicane is now the Department of Crystallography and Biophysics. As a living legacy, GNR (1932-2001) has spawned a dynasty of scientists who work in India and abroad addressing biological questions in structural terms.

In a tribute to a pioneering biophysicist’s original insight, and as a token of their collaboration, CLRI has named its lecture theatre the Triple Helix Auditorium. That name is also a reminder of the time when a fledgling ‘Madras Group’ took on a vexing problem in molecular biology, competed with the best brains in the world, and came out well on top.