Registered with the Registrar of Newspapers for India under R.N.I 53640/91

Vol. XXVII No. 18, January 1-15, 2018

The family’s sole calling card

by P.V. Krishnamoorthy

4-page Margazhi Musings – A special feature

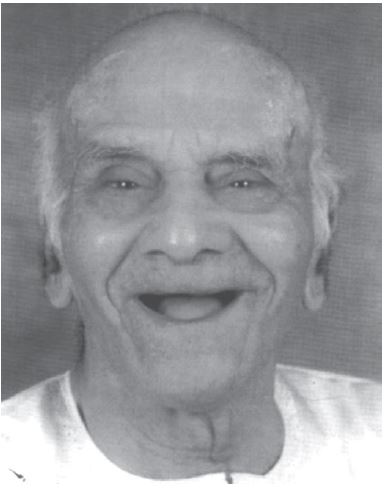

SUBBUDU

Irrespective of the many bureaucratic positions I have held and the awards I have received, I invariably introduce myself to people by saying, “I am Subbudu’s youngest brother” that has opened many doors for me. In fact, all the members of the family exploit their one and only visiting card, “SUBBUDU”.

People have asked me why the name Subbudu. Is there a Telugu connection? Well, yes and no! My maternal grandfather was a Tahsildar in the Guntur District of Andhra Pradesh. The family was at home with Telugu. When the boy was named Subramaniam, my uncles chose to nickname him Subbudu, in the true Andhra tradition, and the name stuck. When Subbudu’s name is mentioned, some pictures of us in Rangoon float in front of me.

My two elder sisters Rajeswari and Pattammal were attending their music lesson with Krishnamurti Bhagavatar. Subbudu, barely eight or nine, was sitting beside the Bhagavatar, listening intensely, keeping talam on his lap and, like a jack-in-the-box, pointing out small lapses in my sisters’ singing. That day, Subbudu the critic was born.

To test the boy’s ability, one day, the Bhagavatar sang a line from a keertana and asked Subbudu to sing it in solfa notes. To the teacher’s surprise Subbudu reeled out the swaras. The next day the Bhagavatar asked my father if he could adopt Subbudu as his sishya and make him a full-fledged musician. My father politely declined, saying that music would always remain his hobby.

This picture takes me to 47th Street East Rangoon. The cosmopolitan city of Rangoon was known for its variety of street hawkers. There was this late evening Burmese hawker selling fried peanuts singing: Maybay salo paasiyan, Maybay salo paasay, or words to that effect!

Our young ventriloquist, Subbudu, repeated his cry accurately and the hawker was surprised and startled. This went on for some days and, finally, one evening, the hawker spotted Subbudu and chased him up to our door. My mother had a hard time explaining to him that it was a mere childish prank. She also had to buy some peanuts to pacify him!

Mimicry came naturally to Subbudu. Even as a child he used to imitate birdsong, animal sounds and even the sounds of musical instruments. One day he tried to imitate the trumpeting of elephants and unfortunately forgot to close his ears which resulted in his hearing a ringing sound in his head for a long time!

Acting was in his blood. There was no drama without his playing an important role, especially a comic one. Playing Hanuman was his forté. He needed no special make-up to play the monkey god. He contorted his face, nobody knows how, and lo and behold, there stood Hanuman!

There was one problem while acting with him. He would suddenly start ad-libbing his own dialogue and his co-actor Ramamurthy (my immediate elder brother) on the stage, would wait endlessly for his cue lines, which never came. The prompter would be tearing his hair in confusion. But the audience would thoroughly enjoy his interventions. Vengusami Iyer, the director, would tell my brother: “Subbudu, you are at liberty to insert your own lines, which the audience seem to enjoy, but for God’s sake get back to your cue lines!”

Even as a youngster Subbudu wrote plays like Prahlada and Seeta Kalyanam to be staged at home with household furniture as props and sarees as curtains. Subbudu played an important role in the musical activities in Rangoon. He was there at the wharf to receive artists visiting from India and spent most of his time with them, attending to their basic needs and creature comforts. For one concert by Muthiah Bhagvatar, the accompanist fell ill and Subbudu volunteered to accompany him on the harmonium. Although reluctant, the vidwan agreed and Subbudu was even paid a sum of Rs. 50 in appreciation.

Subbudu and, we, his brothers were pioneers in introducing Indian music on Rangoon Radio as early as 1936. Tamil Drama troupes also visited Rangoon and Subbudu spent much time with them.

Subbudu used to write short pieces for The Rangoon Times in English, for which he was paid Rs. 2 per piece. He sent some items in Tamil to Ananda Vikatan but his name was not mentioned. Even as a student he won the coveted gold medal for scoring the highest marks in Tamil in the matriculation examination.

Subbudu was spiritually inclined right from his younger days. He would walk five miles up and down to visit a Hanuman temple in Rangoon every Saturday. When we shifted to a suburb, Bauktaw, he organised regular Saturday bhajan-s and nagar oorvolam-s in Margazhi and akhanda nama japa for 24 hours. Even during the hazardous trek from Burma, he chanted Rama Lakshmana Janaki jai bolo Hanumanaki to keep the morale of the trekking party up. He was indeed a spiritual force for the entire community.

Once a friend asked me if I was ever personally embarrassed by Subbudu’s writings. One incident is deeply etched in my memory. My boss in All India Radio and his guru, a veena maestro, went to Germany, where they recorded with M.G. Ramachandran a veena duet with a local gramophone company. On its release, the recording was reviewed by a German critic who was so magnanimous in praise that he wrote that if he was ever banished to a lonely Robinson Crusoe island he would like to take the veena duet recording with him. Next day Subbudu wrote in his column that he would request the critic to ensure that he took not one copy but all the copies of the recording! No wonder I was playing hide and seek with my boss for the next few days.

People have asked me how it was for two brothers to work for the same cultural clientele. My reply has been that there was no clash of interests. My job in the media was to seek the cooperation of artists almost “kaala thottu vela vaanganam” (to touch their feet to get the work done), while Subbudu’s job was “kaala varanam” (to pull the rug from under their feet) if they faltered.

Yes, Subbudu was the universally known music and dance critic, but the human side of this man is not well known. He was not one of those fair weather friends. On the contrary, he would be the first to report at your doorstep when you were in urgent need of help.

We in the family can never ever forget how he voluntarily gave up his collegiate education when there was a financial crisis in the family. He took up a job in the Imperial Bank to keep the kitchen fires burning. One of his most significant contributions to society was when Bihar was struck by its worst earthquake in history. Subbudu immediately organised help in the streets of East Rangoon and went from door to door collecting rice and dal, and hundreds of bags of these were sent immediately to Bihar by a cargo company free of cost. This occasion brought out the organisational, innovative and leadership qualities of young Subbudu. He demonstrated that talent, to be meaningful, had to be harnessed to serve humanity.

When we talk of Subbudu we cannot forget his alter ego – Chandra his wife. What a woman! She was a mother not only to her three children but to Subbudu also. He needed her motherly touch to soothe his nerves. She was a terrific hostess. Her home was always a full house. Was there an akshaya patram in her kitchen?

To sum it all up: Subbudu was made in Rangoon, chiselled in Delhi and sold in Madras! – (Courtesy: Sruti)

The Subbudu story

Sometimes in the mid-nineties, B.M. Sundaram interviewed Subbudu. The remarks in the interview bring out Subbudu as he was – aggressive and hard hitting. Modesty obviously did not rank high in Subbudu’s list of virtues.

My father’s uncle, Mosur Subramania Iyer, asked my father to come to Rangoon, where making a livelihood was easier. So, my parents moved to Rangoon in 1902. I was born on March 27, 1917, in Manali near Chennai.

My father was a strict disciplinarian. He forbade me from becoming a professional musician. If I went out, I had to return home at night, however late the hour. Another reason was that I enjoyed commenting upon the music of others whenever opportunity arose. Hence I did not entertain the idea of becoming a performer. Perhaps it was the second reason that was responsible for my becoming a critic.

I did not, and do not, have an interest in watching sports – be it cricket or any other game, direct or on the TV. I cannot play cards. I read books by famous authors and great scholars. That’s all. I used to write short articles for my school magazine.

I didn’t want to become a music critic. It came about by accident. Gottuvadyam Narayana Iyengar came to Rangoon around 1936. I then wrote a short article for Ananda Vikatan, under the caption Kalai Kappalerugiradu, in which I made a reference to the local vidwan-s – “Ulloor kizhangal irukkumpozhudu Narayana Iyengarin tenisai manadukku perum inbam tandadu” (There are many local oldies, but Narayana Iyengar’s honey-like music gave great pleasure to the listeners). This landed me in trouble. Some among the ‘local oldies’ approached lawyers to issue a legal notice to me. Luckily the sensible lawyers turned them down saying “It is a general view. He has not mentioned anybody by name. So, even if you sue him you won’t win”. I got seven rupees and eight annas from the magazine as remuneration for my first music review. I was 19 at that time.

In March 1942, most of us Indians evacuated Rangoon…We walked and walked – 484 miles – and reached Cherrapunji in a month and 22 days. All through the trek we drew our strength from nama sankeertanam. After stopping at a camp near Cherrapunji, we continued our journey until we reached Simla. My family settled there. I again plunged into music and drama.

My second music review was despatched from Simla. It was about a music recital by Sattur A.G. Subramaniam. He was, no doubt, a good vidwan. But he went on repeating the first line of the song Nee irangayenil ad nauseam. So in my review I remarked that it was akin to coaxing a monkey sitting on a tree to come down! I ended it with the line “This adhika prasangam (impertinence) may please be excused”. But Kalki, after publishing it in Kalki magazine, wrote to me “Adhika prasangam baley jor! Todaravum.” (Impertinence excellent! Continue.) From then on, I reviewed music programmes of artists visiting Simla. After about three years in Simla, I got a job in the Accountant General’s office in Delhi.

V.K. Narayana Menon was the Station Director of AIR Delhi. He was regularly writing music reviews for The Statesman. When he was transferred to Madras, he asked me to do the job, after introducing me to the Editor of The Stateman. I was really nervous, for I was not good at English. But Menon dispelled my diffidence and worry. The Editor of Statesman also called me to suggest that I write reviews. At last I agreed and continued to write for 47 years! I started in 1950 and my first music review published in The Statesman was on M.L. Vasanthakumari’s performance. I like her music very much, it had plenty of imagination, which most of the present day front-rankers are lacking in. However, I didn’t fail to comment that she should take care of sruti alignment. “Let her not follow her master in this aspect.” MLV didn’t mind but appreciated my objective suggestion.

I was regularly writing for Ananda Vikatan and Kalki. In fact, Kalki made me its reporting representative in Delhi. At the same time, I was writing for Idhayam Pesugiradu and Dinamani also. My music reviews were ‘piecemeal’ affairs.

My reviews were not always welcome. If I pointed out mistakes, which musician or dancer would welcome it? I can’t help my reviews being pungent. When you state facts, no one appreciates it. But the public welcomed my reviews. I have made a name in this field, I have my own style and I take pride in it. When I write something, it is easily understood by the common man, which would otherwise be impossible. It is a pleasure for me – you may call it ‘sadistic pleasure’ – but I don’t care! I write what I feel. I have gained in experience by listening to great masters in the field of music and dance. It has taught me a lot more than what the present day artists know. Wherever there is a slip I point it out. If the music doesn’t touch my heart, I don’t hesitate to say so. But writing such reviews was never a bed of roses for me. Many times, it has brought unwarranted trouble.

I am more proud of my style than the content of my reviews. It is my way of writing that attracts the reader. Once Kalki told me, “The readers should forget the music and the musicians reviewed, but should talk about your writing.” I follow that and have been successful in my field. I was born in Vrichika (Scorpio) lagna, and it is but natural that my style of writing would be similar to a scorpion’s sting. The papers for which I write have not curtailed my freedom in any way.

I don’t agree that I raise some artists to great heights and bring down others. Even if it is so, it is never intentional. I go by the stock delivered by them. The artists themselves are not consistent in their performances. If they are good, I say so and if the same artists, on other occasions, are not good, I say so too. This shows that I am unprejudiced.

Nobody has ever come to me with any presents in order to get a favourable review. I don’t expect any such thing. I am far from even entertaining any idea of taking bribes. That’s why artists are really scared of me and avoid me.

As for the complaint that I leave a concert in the middle without sitting through it, I never remain in one place for long. I do not enumerate the songs rendered by the artist, for I am not an AIR announcer! If the artist is not in a position to satisfy my ears while I am in the hall, how could his or her performance suddenly become good after I leave the hall? I get out, whenever I want to do so. I never note down the items rendered on a piece of paper or in a diary. Everything is recorded in my memory. The essence, if any, is reviewed.

Yes, I have made an indelible mark in this field. Otherwise, how could you expect the papers to pay me airfare, provide good board and lodging, arrange an assistant with a typewriter, besides paying me sumptuously! They have high regard for me and my writing. (Courtesy: Sruti)