Registered with the Registrar of Newspapers for India under R.N.I 53640/91

Vol. XXVI No. 22, March 01-15, 2017

No more – In the name of God?

Text & pictures by Simeon Mascarenhas

It is common knowledge that despite official Heritage Committee decres Tamil Nadu prohibiting the demolition of significant public buildings, these laws are flouted on an almost daily basis. While some of these ‘crimes’ are noticed and raise at least a few voices in protest, the Catholic Church seems to have got away with the largest number of demolitions and no one seems to have noticed.

A few years ago there was controversy over the proposed demolition and rebuilding of St Teresa’s Church on Nungam-bakkam High Road. Arguments for and against flew thick and fast, but eventually the original church, built in 1912, was retained and renovated in what most agree is a tasteful manner. A building that has been familiar to citizens of Madras for at least four generations has survived and provides some comforting continuity in an increasingly alienating city.

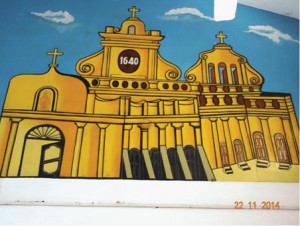

Many churches of far greater historic and archaeological significance, however, have not survived. Take, for instance, the church of Nossa senhora da assuncão, popularly known as the Portuguese Church, in Portuguese Church Street. It was first built in 1640, and subsequently rebuilt in 1749 to accommodate a growing Catholic population of Luso-Indians (people of mixed Portuguese and Indian ethnicity) who had lived in the area for at least 100 years before the arrival of the English. It was demolished in 1993. It is as old as the city of Madras is supposed to be – 377 years – but, sadly, it succumbed to the wreckers hammers.

Even older was the Igreja da Madre de Deus (Church of the Mother of God) in São Tomé (Santhome). This church was built in 1576, handed over to the Jesuits in 1977 and subsequently become part of Dhyana Ashram. It was demolished in 1997 on the grounds that it was dilapidated. This is surprising, given the reputation of the Jesuits for progressive thinking. That reputation is a thing of the past. Any building would be dangerous if it does not receive regular maintenance, but maintenance, along with conservation, seem to be two words that have vanished from most Indian vocabularies.

Also in São Tomé and rebuilt twice is the church of Santo Lazaro, or St Lazarus’s Church. The earliest church records go back to 1582. In 1637, it was rebuilt, again probably to accommodate a growing population. In 1928, during the religious revival of the late 19th and early 20th Centuries, it was rebuilt in late Gothic style, like the São Tomé basilica and thousands of churches across the Christian world. At the time, this style of church architecture offered thinner walls that could support higher ceilings than those of earlier Romanesque designs, allowing more light and the accommodation of a larger congregation.

The church on Little Mount (Chinna Malai) in Saidapet is an excellent example of the type of church built by a small pioneer population. A vastly increased number of worshippers dictated that a larger space for worship be built, and a circular church was added in 1970, adjacent to the original. Part of the original was demolished. The result may not be picturesque, but at least some of the original church (or its rebuilt version) has been retained. The same idea seems to be in the pipeline for the Igreja de Nossa Senhora da Expectação on St Thomas’ Mount, but the focus there is clearly revenue: there are prominent signs everywhere literally screaming “Have you paid for taking photographs/videos/community meals?” even if you are walking up the gravel path leading to the church.

The Church of São Roque (St. Roque’s) is Washermanpet in said to date from 1814, a cemetery for Catholics having existed on the site since 1776. This was the main burial ground for the Luso-Indians of what is now the George Town area. None of it exists, a horrible concrete shed-like structure having taken it place. Even more frightening is the avenue of statues of saints leading to the front door, every one of them liberally painted in colours that will destroy the most resilient of eyes, even those protected with polarised sunglasses. A single glance will do.

Incidentally, what records generally refer to as Portuguese are in fact Luso-Indians who spoke both Portuguese and Tamil, there being very few white Portuguese males and even less white women on the Coromandel Coast until about the beginning of the 19th Century. Intermarriage was simply the norm, especially on the east coast, and the resulting Euro-indian community was the basis of what is today quite erroneously called Anglo-Indian. ALL Portuguese males on the east coast of India, from Cape Comorin (Cabo Cumari) to Ugulim (Hooghly) were private adventurers, deserters from ships due to unpaid wages, men escaping poverty or harsh justice and even the odd deserting priest or two, who settled locally and traded extensively with Malaya, Indonesia, Japan and China. Many became enormously wealthy in the process, to the great envy of the French, Dutch and English.

These European newcomers to India went to great lengths to entice these Luso-Indian families to live under their dubious ‘patronage’. To add to the mix, many sailors and soldiers in the Portuguese forces and on trading vessels came from just about every European nation, especially England, France, Spain, the Netherlands, Switzerland, and West and East Africa. Whatever their origin, they remained Catholic, to the great disappointment and disgust of the Dutch. ALL “Portuguese” churches in and around Madras, therefore, were erected and maintained by local people, born and brought up in the local area, NOT by some far-off foreign “power”. They are products of local finances, local workmanship under an increasing exchange of ideas and techniques, and places of worship for people who had not the slightest intention of going ‘home’. They were home just as much as a local Hindu or Muslim.

The Church Nossa Senhora do Descanso is, as far as I know, not open to the public. It may have been altered since its erection in the 17th Century. I shall have to do more research on this church before I can comment on it.

The biggest puzzle is how a major church, Nossa Senhora da Glória (originally Nossa Senhora de Alegria = our Lady of Joy) in Pulicat, could be demolished ‘without the knowledge of the archbishop’, as the parish priest of a few years ago told me. Pulicat was a thriving town of immense significance for both the (informal) Portuguese presence and the (official) Dutch VOC (Vereenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie = United East India Company), but it fell into ruin after the British got hold of it and systematically destroyed the substantial fort and all major buildings, just as they did in Armagon when moving to Fort St George, in case it fell into the hands of a foreign power and became a threat to English (later British) imperial designs.

Judging from the few remaining pictures, Nossa Senhora da Glória was clearly built in the 17th Century, like most chur-ches in the Iberian world. Alterations and a Gothic front were added in 1888. That’s when the roof was weakened at the junction of the new and the old, the contrast between chunam and cement, making it prone to leaking. In 2012 or 2013, the original church was demolished and replaced by an ugly concrete hulk that sits incongruously next to the beautiful old Hindu temple and a short street away from the exquisite little pioneer-style chapel of St Anthony. The parish priest at the time I visited the village insisted that “nobody, not even the bishop, knew anything about the demolition”. Yet the website of this same church carries a photograph of the Archbishop of Madras-Mylapore, Rev Chin-appa declaring the church a shrine on September 29, 2012. Hmm….

Naturally, a burgeoning population needs greater space for worship. But in the effort to provide this, I don’t see why we cannot preserve the original buildings or at least incorporate them into the new in a tasteful and archaeologically sensitive -manner. No doubt similar destruction is taking place in other parts of Tamil Nadu, particularly in the Tuticorin area. There is no shortage of money in India, and religious organi-sations of every denomination are raking the stuff in like never before.

I have seen churches in Portugal of exactly the same kind of design and construction as the old ones we have in India. Many are even older than the Indian churches, and they are in perfectly good condition. Bricks and chunam hold up extremely well in our Indian climate, as long as water is not allowed to seep into it. Hence the sloping tile roofs.

Every single Catholic church in and around Madras carries the name of a similar one in Portugal: Tomé, Antonio, Roque (pron. ro-kay) and Sebastião are all extremely important saints in Portugal. Our Lady reigns supreme, especially after João IV of Portugal consecrated the Crown of Portugal to the Virgin Mary in 1646. No monarch of Portugal has ever worn a crown since then, although a diadem was present at state functions until the abolition of the monarchy in 1910.

One of the most sensitive renovations I have seen is that carried out on Votive Shrine, Kilpauk, a church built in 1952, and which incorporates representative architectural features of European, Islamic and Hindu traditions. But what of the older, very historic churches? How many more of them will be quietly demolished to make way for an increased number of donations? In most other (and enlightened) countries the preservation of historically significant religious buildings ensures a steady income from tourists, many of them with no religious beliefs whatsoever. It also does wonders for national pride. Short-sightedness on the part of our authorities can only do -damage that can never be -reversed.