Registered with the Registrar of Newspapers for India under R.N.I 53640/91

Vol. XXVI No. 04, June 1-15, 2016

When the Raj had an Agent in Ceylon

by K.R.A. Narasiah

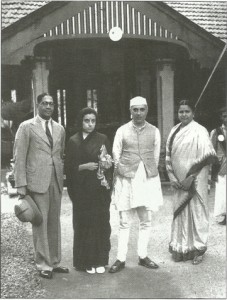

Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru and Mrs. Krishna Hutheesing with Mr. and Mrs.

Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru and Mrs. Krishna Hutheesing with Mr. and Mrs.Pai in front of their residence in Kandy July 1939.

The Raj Agent in Ceylon 1936-40 is a book by Sharada Nayak, the daughter of Ammembal Vittal Pai, an ICS officer who served both sides of Independence. The narrative takes us through some important phases of the history of Indo-Ceylon relations during the crucial years between 1936 and 1940. In his foreword, G. Parthasarathy, former Foreign Service officer, recalls the sterling role played by A V Pai in dealing with the growing demands from the Sinhala political leadership for the repatriation of a large number of Indian Tamils. Parthasarathy himself was designated later by the then Prime Minister, Rajiv Gandhi, to handle issues pertaining to the fall out of the presence of the Indian Peace Keeping Force (IPKF) in Sri Lanka between 1987 and 1989. Therefore his stating in his foreword that “this book draws attention to some of the historical complexities in building a vibrant, multi-ethnic, multi-lingual and multi-religious policy in Sri Lanka” lends significance to the work of Sharad Nayak.

Born 1901, in Calicut, A.V. Pai, after his early education in Mangalore, graduated from the Presidency College, Madras, proceeded to England for further studies in Wadham College, Oxford University, and was called to the Bar in 1925. As was with many a bright student from India, he appeared for the exam and got inducted into the Indian Civil Service. Pai married Tara, the only daughter of Dr. Kesava Pai, well known in Madras for the treatment of Tuberculosis. Dr. Kesava Pai retired as the first Indian to head the King’s Institute, Guindy.

With the passing of the Emigration Act, the Government of India established an Agency in Ceylon in 1923. This was manned by an ICS officer known as the Raj Agent in Ceylon. Pai, who had been assigned to the Madras Presidency cadre, was serving in Kumbakonam when he was sent to Ceylon in 1936 as the Agent of the Indian Government in Ceylon.

His daughter, Sharada, author of the book, remembers the excitement they felt as children when they boarded the Indo-Ceylon Express at Egmore where the Health Officers checked the immigrants. She recalls Mandapam camp, run by the Government of Ceylon, where the officials checked the applications of workers from India proceeding to Ceylon for a living. The kanganis were the recruiting agents for the tea estate owners of Ceylon and the workers obeyed them without murmur due to their state of poverty and lack of employment in India. The job-seekers were herded into large sheds with their families, little knowing what awaited them in the island but hoping for a better future. It was much later that the author learned that those groups of ragged peasants were the reason for the journey of her family to Ceylon.

She remembers that as a child of barely 5 she was told the reason for the name Dhanushkodi – it was Vibhishana who, when crowned by Rama, said, “Oh Rama, as long as we were an island the sea surrounded and protected us. Now that you have built a bridge we are vulnerable.” Rama with his bow struck the bridge and broke it. Broken by a bow (dhanush), the place came to be known as Dhanushkodi.

The Pai family was to live in Kandy, in the hill country, a place of great natural beauty; Pai did not take the house his predecessor, K.P.S. Menon, had lived in, but took The Orchard with its pretty, sloping garden lined with durian trees. Sharada’s sisters were Kanaka and Shanti. Their mother introduced them to their neighbour, Mrs Jonklaas, a Burgher family, who remarked, “You have Wealth and Learning and Peace!” (meaning Kanaka, Sharada and Shanti).

Vittal Pai’s immediate interest after taking over as Agent was education and healthcare for the workers’ families. P.T. Rajan, who had migrated to Ceylon, and was in his early twenties, had founded Indian Students’ Hostel in 1935. At its first anniversary, the Pais were the guests of honour. (In 1951, at the suggestion of Rajaji, the name was changed to Ashoka Students’ Hostel.)

When the slavery system was abolished and an indentured labour system introduced by the West, it was easy for those others who needed labour to adopt this system, though there was no change in exploitation of the workers. The kanganis recruited and sent more than 70,000 immigrants to Ceylon in 1934-35 alone. Sharada narrates that the Nattukottai Chettiars in Ceylon were a force to reckon with as they controlled to some extent the economy of the island. She feels that with so many Indians contributing to the economic activity of the island, there was considerable prejudice and overt discrimination against them, particularly if they were unskilled labour.

Two matters that took up considerable time and travel in 1937 and 1938 for Pai were the contemplated eviction of Kandapola cultivators and the Village Communities Ordinance. To have first-hand knowledge, Pai visited 49 estates. In 1937 the Governor of Ceylon was Sir Andrew Caldecott and under pressure from Ceylonese leaders, he appointed a one-man commission to study the problems of immigration. Sir Edward Jackson was the appointee and Pai, as Agent, gave his report. During 1931 and 1932 the wages were cut for the workers and the Agent in his report asked that the migrant labour be treated as Ceylonese and given the same rights and dues.

The book’s most important chapter is the visit of Nehru to the island in July 1939. Accompanied by Krishna Hutheesing, his sister, he drove around the island with Pai. He visited the tea gardens to understand the problems faced by the Indian workers. When Nehru returned to India, he sent his notes to Pai to examined for correctness. An entire chapter is devoted to the correspondence between Nehru and Pai and throws light into their deep sense of commitment to solve problems in the beginning itself.

The complaint of the workers taking away money from Ceylon to India was disproved by C. Rajagopalachari, then Prime Minister of Madras Presidency, by quoting figures from the transfers through the Post Offices of both countries. He said, “On an average it was not more than Rs. 10/- per person, for it was hardly likely that the estate worker would have savings to send home, when he was in deep debt to the kanganis and the shopkeepers.”

The book, quoting extensively from later accords between the two countries, is a mine of information for scholars wanting to research Indo-Sri Lankan relations as far as the Indian Tamil issue is concerned.

(Sharada Nayak the author, after studies in Madras and Delhi Universities, proceeded to the US on an international scholarship to study at Briarcliff College, New York. Until 1992 she was Executive Director of the United States Educational Foundation in India which administers the Fullbright exchange programme.)

I got the book from Sharada herself and found it very interesting and dear. I know Sharada from her study-time in the USA, especially from our joint participation in a Lisle Fellowship Unit in California in the summer of 1954. I had been a foreign student (from the Netherlands) that year at a Girls College (Lindenwood University now) in St.Charles. MO. Sharada and I had something in common as far as our parents are concerned: I have made a transcription of the dayly letters my parents wrote to each other during 1 and a half years that my father was a hostage in a hostage camp in Holland by the Nazi’s from June 1942 until december 1943. They died a week after each other in 1989. In 2005 I finished the transcription, To get te learn one’s parents this way and to learn about the dayly war experiences (I was 5 years old when the Second World War started) is very, very special. Sharada’s experiences must have been somehow the same.

I got the book from Sharada herself and found it very dear (close) and interesting. I know Sharada from a joint Lisle Fellowship Unit in California USA (both foreign students) in the summer of 1954. Later in life we had something else in common. I made a transcription of the dayly letters my parents wrote to each other during WW II, when my father was in a Hostage Camp of the Nazi’s in Holland, during 1 and a half year. One learns to know one’s parents in a dear, very special way!

I know Sharada from a joint participation in 1954 at a Lisle Fellowship Unit in Califotnia USA. Later in life we had something else in common: I made a transcription of the dayly letters my parents wrote to each other during 1 and a half year, when my father was imprisoned in a Hostage Camp of the Nazi’s, in Holland. One gets to know one’s parents in a very dear and special way!

I got to know Sharada during a joint participation of a Lisle Fellowship Unit in 1954 in California USA. Later in life we had something else in common: I made a transcription of the dayly letters my parents wrote to each other during the 1and a half years that my father was imprisoned in a Nazi Hostage camp in Holland (WWII). A very special and dear way to get to know one’s parents!