Registered with the Registrar of Newspapers for India under R.N.I 53640/91

Vol. XXVI No. 08, August 1-15, 2016

A Prime Minister in (en)action

by Sriram V

Remembering the Raja

(continued from last fortnight)

Ramarayaningar when he was the Chief Minister of Madras.

Ramarayaningar when he was the Chief Minister of Madras.

It must be recalled that the Justice Government formed in 1921 was elected by a limited franchise and that the real executive powers continued to vest with the Governor and the bureaucracy.

In such a scenario, not much was expected of Ramarayaningar and his cabinet of two members, these being Kurma Venkata Reddy Rao Naidu, in charge of Development, and Aneppu Parasuramdas Patro who held the portfolios of Education and Public Works.But he and his colleagues did choose to leave behind a lasting legacy.

Law & Order was one of the key portfolios that the Governor kept to his Executive Council. The elected Government was therefore not technically responsible for maintenance of public peace, which was at that time disrupted owing to a prolonged strike in the Buckingham and Carnatic (B&C) Mills, Pulianthope. The management, with the active connivance of the Government (read Governor and Council), resorted to divisive tactics by appealing to the Adi Dravidas among the workers who broke away from the Unions and reported for duty. The Mills were re-opened but at an enormous toll – the Adi Dravida colonies surrounding the Mills were gutted, the police resorted to firing and there was loss of life. The Government moreover suggested that the cost of maintaining peace ought to be borne by the residents of the locality. The Justice Party immediately sent out a delegation to study the situation and this resulted in an adjournment motion in the Legislative Council, brought forward by O. Thanigachalam Chettiar, a leading member of the Party. Actively supported by Ramarayaningar, the motion, which censured the Government – chiefly the Labour Commissioner and his staff in the handling of the issue – was passed by an overwhelming majority.

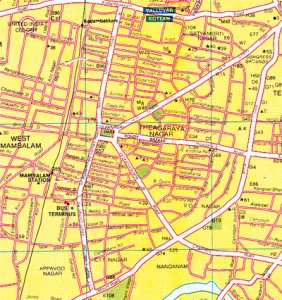

The planned residential area Panagal dreamed of

The planned residential area Panagal dreamed of

It was also with the assistance of O. Thanigachalam Chettiar that Ramarayaningar brought forward his first significant legislation – the representation of non-Brahmins in Government jobs. Piloted in the Council in August 1921, this was to be hotly debated, with members such as B. Srinivasa Rao and L.A. Govindaraghava Aiyar opposing it and others such as R.K. Shanmukham Chetty staunchly in favour. The Government’s Law Member, A.R. Knapp had to repeatedly intervene and work out a compromise. The net result was the famed Communal GO by whose terms, 44 per cent of all Government jobs were reserved for non-Brahmins, 16 per cent for each of three groups – Brahmins, Muslims and Christians (inclusive of Anglo Indians) – and 8 per cent for what would today be referred to as Scheduled Castes and Tribes. Widely reported then as a pioneering attempt at social reform, it is considered today to be the first step in inclusivity in the whole of India. The bill as originally proposed by O Thanigachalam Chettiar stipulated such reservation for a period of seven years, till equality was achieved. Its subsequent history has been different, as is well known.

Ramarayaningar then began taking steps to implement another of his pet reforms – the administration of temples and Hindu religious establishments. These were at that time mostly under the control of mahant-s, adeenam-s and other pontiffs. The shrines owned vast tracts of land and most of these were poorly handled, resulting in very low or no revenues. Ramarayaningar suggested the setting up of a Hindu Religious Endowments Board and by end 1921, this too was approved by the Legislative Council. The forerunner of today’s HR&CE department of the Government, it saw the wholesale takeover of all temple and mutt administrations. Ramarayaningar’s sentiments behind the move were laudable and received wholehearted support from the Paramacharya of Kanchi but its subsequent implementation has been a mixed legacy at best. A year later, another pioneering piece of legislation – the Madras State Aid to Industries Act was passed. This made it a State policy to extend loans to developing industries in the Province.

The second general elections in Madras were held in 1923 and the Justice Party won a majority. Ramarayaningar, now conferred the honorific of Raja of Panagal by the Government, was invited to become Prime Minister. There was a change in his cabinet – T.N. Sivagnanam Pillai became Minister in place of K.V. Reddy Rao Naidu. With Patro being the other member, the combination of names led to a widespread joke – Pana(n)gal (toddy) in a Patro (vessel) led to Sivagnanam (bliss). The new cabinet faced its first challenge almost immediately when a section of the Justice legislators, led by Cattamanchi Ramalinga Reddy, broke away and formed the United Nationalist Party. They tabled a no-confidence motion against the Panagal Government. With the redoubtable orator S. Satyamurti also in the Council as a Swaraj Party member, the debate on the motion was lively, his wits being pitted against speakers such as Panagal and O. Thanigachalam Chettiar. The motion was defeated – the Nays leading 65 over the Ayes 44.

The new Government focused on reforms in education. It passed the Madras University Act that reorganised the functioning of that body. It saw to the creation of a Governing Body, headed by the Governor as Chancellor, the Minister for Education as Pro-Chancellor and the creation of the office of a full-time Vice Chancellor. In 1925, the Andhra University Act was also passed. The same year, Panagal was greatly instrumental in the setting up of the Government School of Indian Medicine, headed by Capt. Dr. G. Srinivasamurthy. To house this institution, Panagal donated Hyde Park Gardens, his property at Kilpauk. The Kilpauk Medical College now functions from this campus.

During his tenure as Prime Minister, Panagal brought in a complaint of cheating against Murugesa Mudaliar, a well-known diamond merchant. It was found that emeralds purchased from him by the Raja were not up to the weight that they were originally claimed to be. By then the third general elections were due in Madras. Conferred a knighthood by the Government, the Raja of Panagal chose his trusted lieutenant O. Thanigachalam Chettiar to be his lawyer in what became known as the Raja of Panagal case. The election campaign was intense and resulted in no party acquiring a majority in the Legislature. Panagal chose to sit in the opposition even as Dr. P. Subbaroyan was weaned away by the Swaraj Party and made to cobble together a coalition government of sorts.

In the meanwhile, the case concerning the emeralds went on. The defendant had the formidable Nugent Grant as his lawyer. Despite his exalted status, Panagal chose to appear in court and submit himself to a grilling cross-examination by Grant. The key witness was Professor N.G. Ranga, later to become a respected parliamentarian and representative of agrarian interests in free India. The case ended in the acquittal of Murugesa Mudaliar.

It was during his tenure as Prime Minister that the long pending proposal to drain the Long Tank of Mylapore and develop it as a residential area gained ground. Panagal and his ministers ensured that the work began in right earnest. Work would continue for long but by then Panagal was dead. He passed away on December 15, 1928, much mourned by all. The Long Tank would eventually give way to T(heyagaroya) Nagar, named after Panagal’s mentor Sir Pitty Theagaroya Chetty. Its focal point, developed as a park, was named after Panagal and eventually came to house an exquisite bronze statue of his by M.S. Nagappa, alas now coated with gilt (as would have been seen in older picture last fortnight).

(Concluded)