Registered with the Registrar of Newspapers for India under R.N.I 53640/91

Vol. XXVII No. 1, April 16-30, 2017

Lost Landmarks of Chennai

– Sriram V

The growth overrun cemetery

Being overrun with growth.

Being overrun with growth.Technically speaking, this vast patch of land on The Island now more or less under the great bridge to Central Station that replaced the Stanley Viaduct, belongs to the Church of St. Mary’s in the Fort. In reality it appears to belong to no one, such being its state of neglect.

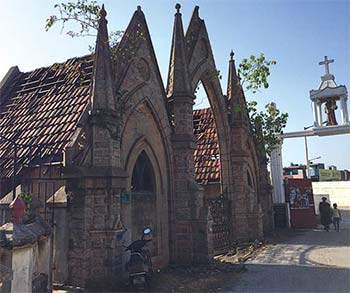

Formerly known as the English Burial Ground on The Island, the St. Mary’s Cemetery is now accessed from Pallavan Salai (old Band Practice Road). You need to make a sharp left just after the Bodyguard Muneeswarar Temple, taking care not to get onto the overbridge that takes you to Central. The cemetery proper is accessed through a Gothic Revival gateway that has three pointed arches supported by thin pinnacles. Of the two flanking arches, the one on the right is bricked up, while that on the left is now the principal access. The central arch, through which the coffins and the mourners must have once passed, has grille gates that are permanently locked. The two flanking arches are followed immediately by the waiting rooms where mourners must have once gathered prior to the burial. Mangalore tiled sloping roofs, supported on timber frames, top these. The sexton’s residence is to the left of the main gate and this is where the caretaker and his family now live.

The oldest English burial ground in Madras was at the Guava Garden, on which site now stands the Law College. That Golgotha proved to be a security risk when the Comte de Lally and his French forces laid siege to Madras in 1758. Once the attackers had been repulsed, work began on securing the city from future invasions and among the many measures taken up was the flattening of the monuments that stood in the Guava Garden. The surviving tombstones were taken to the yard surrounding St. Mary’s in the Fort leaving behind two monuments – the Hynmer Obelisk that still survives and the Powney Vault that vanished once Metro Rail began its work in the area.

The new burial ground came up on the Island in the early 1760s. The earliest interment here – that of William Rogers – is dated May 14, 1763. Nine years later, when Governor Nicholas Morse was laid to rest here, the place was still being referred to as the new cemetery of St. Mary’s. The ground allotted was enlarged in 1782 and a thin brick wall was put up all around it, replacing the earlier Palmyra fence that proved no defence against marauding jackals and dogs. It is quite likely that the Gothic gateway too dates to this period.

The entrance to the cemetery – partly walled-in

The entrance to the cemetery – partly walled-inFrom then on till 1817, when St. George’s Cathedral became the principal church for the city, the Island cemetery was where the powerful, the important, the rich, and quite a few commoners among the English came for their eternal sleep. Burials continued happening intermittently here till the 1880s, by when the cemetery was officially declared closed. However, a casual glance will show you that occasional burials continue to happen, especially if the dear-departed is a parishioner of St. Mary’s.

The monuments here vary when it comes to shape and size. Some, such as that of Dr. James Anderson, the great botanist, are buildings by themselves, made of brick and clad in stone. Others, like that of the lawyer turned speculator Stephen Popham, are great slabs of granite. Some like that of James May, the first superintendent of the Madras Harbour Works, stand out because of some unique aspect. This one has four granite columns rising up to hold a hipped roof on which is the funerary inscription.

Wandering around, the appalling mortality is what strikes you first. Most of the dead did not cross fifty. Whole families lie here, with children far outnumbering the adults and women being more than men. Next comes the realisation that this cemetery needs some urgent restoration. Several of the monuments have trees growing out of the crevices. Many of the granite slabs have vanished or have been vandalised. Dr. Anderson’s tombstone has shattered into several pieces for instance. Cyclone Vardah has added to the ruin by uprooting several trees. A giant peepul is still where it fell, on four giant tombstones. The tall grass that abounds makes this cemetery an ideal open-air toilet for the slums that abut the station. The number of shards from liquor bottles tells you of other uses that place is put to. A gaping hole in the wall on the northern side provides easy entry and exit to people who want to use the cemetery for clandestine purposes. A single caretaker cannot manage this vast expanse of land, and at night he may perhaps not want to stir out of the not so comfortable home he has on the premises. Certainly, he is unaware of the history of what he is supposed to protect, or its importance. The police are regular visitors here but their control is rather limited.

Occasionally, St. Mary’s Cemetery springs to life. That is when the premises are allowed for film shoots, one of the earliest perhaps being the Rajinikanth starrer, Billa. It is indeed a pity that the Church and whoever else is supposed to be in charge of the upkeep, should allow the cemetery to languish. It cries out for basic maintenance – cleaning up of the shrubbery, proper walkways, signposts to indicate the important tombstones and if possible, a guidebook. It is understood that a University in the UK has recently come forward to assist in restoring the place and making available all the above features. The onus is now on the church to respond.

In sharp contrast to the general squalor of the cemetery is the manner in which one corner – the Commonwealth War Cemetery – is maintained. Here the stones are neatly aligned, the lawn mowed and the floral borders tended to. Close to this pocket is the grave of Brigadier Nicholson and his wife Adela Florence, who under the pseudonym Laurence Hope wrote several poems, the most famous perhaps being Pale Hands I Loved Beside The Shalimar.

Next door to St. Mary’s Cemetery is that of the Roman Catholic Church of St. Patrick’s. It is as shabby as the former and has to its dubious credit some recent hideous structures such as a square archway and a pillar of many blocks topped with an illuminated statue of Jesus. There is in addition a platform for prayer that is now put to less spiritual use. In the near vicinity is said to be a lost Presbyterian Cemetery and another one belonging to the Armenians.

Hai..

I am a social worker, every day u used to see this place while traveling in train…

And I’ve read various article writer by ur founder n The Hindu since 2015.

As a individual I wanted to do something to restore this place.

I spoke about it to my friends and now a bunch of socially conscious people are ready to clean the place and renovate it…But the problem is, we don’t know whom to contact to get permission for the clean up.

It would be very nice if u can guide us to the right person…

Thank you..