Registered with the Registrar of Newspapers for India under R.N.I 53640/91

Vol. XXVII No. 17, December 16-31, 2017

The most unforgettable Briton the City has known

S.R. Madhu

He sported the fancy title of Director of Photography, Indian Express Group. (I doubt if any other major newspaper in India has ever had such a functionary.) This Briton’s friendship with the Madras police (who frequently sought his help for photographs of criminals and crime scenes) and the access he enjoyed to top brass in government and elsewhere made him an influential person. You crossed him at your peril.

Voluble, witty, entertaining and highly self-opinionated, Harry Miller was always ebullient company.

Miller made Madras his home in 1956 and lived here till his death in 1998. He had earlier represented The Hindu as its London correspondent and was even for two years its correspondent in Pakistan, a country he disliked intensely. He went back to the U.K. and lived there for seven years before coming to Madras – a city “that gave him the powerful feeling that this was home.” He married Revathi, daughter of Parthasarathy Iyengar aka ‘Sadhu’ Parthasarathy (a leading lawyer of Chennai who took to sanyas after building the Vaishnavi temple in Thirumullaivayal).

Miller joined the Indian Express in the 1950s and did pretty much what he wanted to do. He published provocative and occasionally eye-stopping photographs. He wrote a popular column, ‘Madras – city of neglect’, about civic problems – clogged sewers, uncollected rubbish, poor bus services, failing streetlights, illegal buildings. And undertook important photographic assignments.

Back in 1980, I was Miller’s companion over several thousand kilometres of road journeys – in Chennai, Mahabalipuram, Kanniyakumari and Tuticorin in Tamil Nadu; Kakinada and Uppada in Andhra Pradesh; Puri in Orissa; Chittagong and Cox’s Bazar in Bangladesh; Colombo, Negombo and Beruwela in Sri Lanka. He was particularly loquacious in a car – car journeys seemed to at once unravel his memory and loosen his tongue. Result: stories, anecdotes and jokes aplenty – about Madras, its personalities high and humble, animals and snakes, the Indian Express – some of which were known to very few.

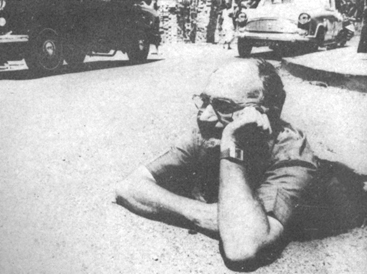

Harry Miller in typical ‘action (above) and some of his photographs (top) for the Bay of Bengal Programme’s exhibitions.

Why the car journeys? As Information Officer of a FAO/UN project, the Bay of Bengal Programme, I had suggested a photo exhibition on small-scale fisheries to raise public awareness about our work. The project director, Lars Engvall, readily agreed and suggested that we engage Harry Miller, whom he knew through the Madras Club, to photo-document our work in India, Bangladesh and Sri Lanka. I accompanied Miller on field trips in the three countries to brief him about our work.

Miller took several hundred photographs for the Bay of Bengal Programme, and we held two successful photo exhibitions – one at the Taj Coromandel in Madras, another at the Galle Face Hotel in Colombo. The exhibition began an association both instructive and entertaining.

But what I would like to talk about today are the stories and anecdotes Miller shared with me on those car journeys. One delightful story concerned his boss in the Indian Express, Ramnath Goenka – or, rather, about an orphanage Goenka had set up in Chennai for destitute boys. He once told Miller “These boys are on vacation from school. They are idling away, wasting time. Teach them photography.” Miller took the chore seriously and imparted to the children the basics of composition and focal length and lighting.

Around that time, a friend of Miller, a visiting British fashion photographer, had left a few rolls of precious negatives with Miller – of some luscious ladies in the nude. He told Miller, “I’m going out of town for some time. I don’t want to keep carrying these negatives around with me. Keep them safely for me till I come back.” Miller kept the negative wallets in a darkroom cupboard.

One afternoon, Miller took the orphanage kids out on a photography field trip. He then told them to process and print in his darkroom what they had shot, while he went out for some time. When he returned a few hours later, what did he find?

The kids were on the floor giggling and sniggering, huddled over several prints of women in the buff. They had somehow discovered the “steamy” negatives, and used their new-found skills to process and print them! Miller is known to have a short fuse, and I pity the victims of his wrath.

Miller told me, “For Heaven’s sake, Madhu, don’t write about this anywhere. The Old Man won’t forgive me. But do what you want after I am gone.” Since neither Miller nor “The Old Man” is around anymore, I guess it’s okay to share this anecdote with readers.

Another Miller anecdote: Miller was interested in temple architecture and his TamBram father-in-law put in a word with the temple authorities in Rameswaram for a special darshan for his son-in-law. Miller decided to go to the temple bare-chested and clad only in a dhoti (without underwear). The temple elephant raised its trunk to give Miller a well-trained namaste, encouraging him to draw closer.

“Something incredible then happened,” Miller said. “Perhaps the elephant had never seen a white man before. It suddenly twirled its trunk and removed my dhoti.” The photo director of the Indian Express was in the altogether. “There was a photographer around,” recalls Miller. “What a stupid fellow. Instead of snapping a fantastic moment, he covered his eyes with his hands and looked away!”

Miller asked me why Tamilians are so colour-conscious. He said he once photographed K. Kamaraj, the former Chief Minister of Tamil Nadu. “I thought they were pretty good photographs. But Kamaraj’s response was ‘You have made me look so black’.” Miller said Indian photographers sometimes used “red-ink treatment” to make their subjects fairer.

Miller could resort to bluster to overcome difficult situations. (“As a vellaikkaran, I get away with some nonsense in Madras!”) He told me that on one occasion, he arrived at Madras airport from London with some expensive photo equipment bought in the U.K. He apprehended heavy import duty. When the Customs asked him whether he had anything to declare, he replied, “Yes, I have a gun.”

This triggered consternation. “He has a gun,” the Customs officer yelled out to his colleagues, and they gathered around him. “Why do you have a gun, Sir?” one of them asked. “To shoot mad dogs,” Miller replied with a straight face.

“Dogs? Why?”

“Have you ever carried dying children in your arms, children with rabies? I have done that. Believe me, there can be no death more horrible.” The audience of Customs officers were tongue-tied and all ears while Miller gave them a zoology lesson. He said people harbored an irrational fear of snakes, most of which were harmless. But they were indifferent to mad dogs which freely roamed the city and spread rabies. “I shoot them to save the people of Madras.”

“Do you have a licence for the gun, Sir?” asked one of the officers.

“No, I must apply for one,” Miller said. “Please leave the revolver here till you get the licence,” he was told. “Okay, may I leave now?” asked Miller. Yes, said the Customs guys, and Miller left the airport without paying a paisa as duty for the camera equipment! He retrieved his revolver later. I didn’t ask Miller what use he put it to.

Miller had had an encounter with the Customs earlier. He occasionally received protein-rich “whole milk biscuits” from New Zealand for distribution to poor children in Thirumullaivayal. On one occasion, he received a notice from the Customs demanding Rs. 25,000 for a consignment. Miller tried to argue that the consignments were non-dutiable and for charity. Even the New Zealand High Commissioner in India supported his claim. But the Customs did not relent. They even billed Miller Rs. 50,000 for two earlier consignments!

On an impulse, Miller dashed off a long telegram to Prime Minister Indira Gandhi. He had met her and Pandit Nehru a couple of times in London while he was a correspondent for The Hindu. He reminded her of those meetings and complained that he was being penalised by the Customs in India for charity work for children. The PM did not reply, but a week later, the Customs guys phoned him most courteously and respectfully, and said, “Sir, we have waived the Customs duty for the milk biscuits. We will deliver them to your place. When can we do so?” The children got their biscuits

Miller was a naturalist and wildlife enthusiast, particularly knowledgeable about snakes. He wrote an article for National Geographic in September 1970 on ‘The cobra, India’s good snake’. For many years Miller’s home in Chennai was a two-acre house in Thirumullaivayal (in Thiruvallur District, near Avadi) – that he built on land gifted to his wife by his father-in-law. Visitors to the house in a rural setting were varied – frogs, snakes (including cobras, kraits and vipers), monkeys, pigs, mongooses and many strange insects. Miller frequently received a frenzied SOS from neighbours about snakes intruding into their homes. Priests of the Vaishnavi temple in Thirumullaivayal depended on him to get rid of the snakes slithering in their compound. He kept a pet python in a cupboard, and once offered to garland me with it. I fled before he started insisting!

It was Miller who introduced Romulus Whittaker (founder of the Madras Snake Park and later of the Crocodile Park) to the snake-catching Irula tribes of Tamil Nadu. Rom was so impressed with the Irulas and their skills that he moved from Bombay to Madras so that he could work with these tribes and sell venom from them to the Haffkine Institute in Bombay.

It was also Miller who invited S. Paul, brother of Raghu Rai, to join the Indian Express in New Delhi as its chief photographer. Paul accepted and worked with the Express for 26 years, when he cemented his reputation as one of the pioneers of photo journalism in India.

One of Miller’s most enduring contributions to Madras was in preserving a precious collection of a few hundred glass plate negatives of old Madras and more of other parts of India. These were photographs shot by German and English photographers during the period 1870-1930. The value of these high-quality photographs is inestimable. Its Madras component is the only authentic photo documentation of the city of that period.

How did Miller come by this collection? An aging and impecunious Anglo-Indian nanny in Coonoor, one Miss Cooper, had with her four huge custom-made teak boxes crammed with glass plate negatives. They were left with her by a German family she had worked with in Madras. She didn’t know what to do with them. She showed Eric Stracey, then Inspector-General of Police, the collection when he visited and he had them moved to Madras where he gave them to Harry for preservation. Miller found that the collection comprised some 1,500 glass plate negatives of various Indian events and places, including more than 300 of Madras. Miller years later sold the collection to Vintage Vignettes, a five-man partnership with a sense of history.

One of Miller’s friends was the legendary British futurist, astronomer and science fiction writer Arthur C. Clarke, author of 2001, a Space Odyssey and other novels. Clarke settled in Colombo in 1956 and lived there till his death in 2008. Miller and Clarke often visited each other. Clarke wrote a foreword to one of Harry Miller’s books, A Frog in My Soup. Titled ‘Miller of Madras’, the foreword said, “I have always enjoyed Miller’s splendid photographs and hearing his fascinating stories, many of which may even be true.” He added: “He has an unparalleled understanding of India, its people and its animals …There must be few Westerners who can match his knowledge of this endearing and sometimes infuriating country.” Clarke also described Miller’s house in Thirumullaivayal as a “menagerie” and said Miller had wrapped his pet python round him.

Miller told me an anecdote about Clarke which was perhaps true. Clarke migrated to Ceylon because of his interest in scuba-diving. (He set up a diving school in Hikkaduwa.) Miller said Clarke persuaded the Ceylon Government to give him tax-free status; he told them that if they did so, many Western millionaires would move to Ceylon in the hope of similar treatment. The Government acceded, and amended its laws to make this possible. But the promised migration of Western millionaires to Sri Lanka did not happen. The particular law came to be known informally as the Arthur Clarke amendment.

I once asked Miller why he chose to live in India rather than Britain. “Who wants to live in that bloody cold country?” he wisecracked. But when someone else posed him the same question, he replied “Who else except Indians will tolerate a guy like me?” I suspect the real reason is that Miller had got used to being pampered in Madras and India – servants, assistants, VIP treatment – which he wouldn’t have received back home! He liked the Madras weather; he also liked people looking up to him or fussing over him.

Journalist Rahul Singh, former editor of Reader’s Digest, once told Miller an amusing story of two boys talking to each other at the swimming pool of the Gymkhana Club, Bombay. One boy bemoaned the fact that his father had been transferred to Madras, and that he would henceforth have to live in that rotten old place. The other boy responded, “Oh, Madras can’t be all that bad. Harry Miller lives there.”

Miller says in one of his books that India is a land of amazing variety and contradictions, “also a land of friendly, warm-hearted people, where I have chosen to spend the larger part of my life, where I shall certainly die, and which has given me more happiness than any man could justifiably deserve.”

Miller passed away in 1998. The event was mentioned by all local papers, but it didn’t hit the headlines. Considering his many contributions to Madras that is Chennai, he deserved a more handsome tribute.

The British who loved Madras.

A very nice article about Harry Miller….wondering if his home still exists in Tirumullaivayal….apparently my grandfather who passed away in the 1930s…he was barely 32 years old then, was from Tirumulaivayal. I have met Sadhu Parthasarathy in 1976 at the temple…wondering if I could get some more information about my paternal grandfather A. Ramaswamy Iyengar ….an eminent lawyer at the Madras High Court and brother of A. Krishnamachari (also a lawyer) and A. Narasimhachari (who moved to calcutta)

I lived in Madras as a boy and had the great good fortune to meet Harry(a good friend of my father’s) on many occasions. He gave me a life long love of nature and introduced me to my first pet mongoose and first ‘pet’ snake (a Russels Earth viper).

The epitome of a Welshman abroad and much much more, with stories of India and tall tales growing in stature with each re-telling.

The world would be a far richer place if there were more Harry Miller’s striding across it.

An excellent write up about Harry Miller, a person who brought in a natural dimension to still photography, particularly covering VIPs and Politicians line M/s, Rajaji, Kamaraj, Anna, Kalaignar etc and also creating extremely good coverage of the Heritage buildings and Madras City.

I was an young art student and interested in pencil drawings .About 49 years back I saw a very small stamp size photo of Shri Rajaji in a Bhavan”s Journal . I was keen to draw that., and hence was in need of a copy of the original photoournal. I understood the photograpaher was Harry Miller of Indian Express. I went to Express Estate and was waiting for him in the morning. The moment he came, he asked me to come and I explained the purpose of my visit. He was very happy. He asked me whether I am keen of the same photo or interested in seeing some more of the same roll. Till that time I had never seen a foreighner that too world class photographer with such an amount of courtesy to 33 year unknown man claiming interest to draw. He took me to dark room and shown 12 photos of the same roll. I was taken a back. Really I picked up another pose which I felt better. In no time he printed a Cabinet size copy and handed over to me. I drew a more than double life size of that photo by pencil and mounted it immediately for showing to Shri Rajaji on his birthday of 1970. I completed and showed the same to Shri Rajaji on his birthday in West Mambalam Swathanthra Party Office or residence I am not sure.and he was astonished to see the large size executed very well. He asked” Enna Vibhareetham “.

I mentioned it from the photo taken by Harry Miller. He appreciated me for the work and signed ” CR”.

Next day I met Harry Miller and informed him and he was very happy.

I cannot forget the gesture shown by him to me in my life time. Thank You.

In fact my first job offer ever received was from Harry, he wanted to hire me when I went to him for some other favour. He hired me on the spot and sent me to Venkatraman the presonal manager. Venkatraman for some reason dint want to hire me and asked me about my caste. I refused to him saying, I dont want to work in an environment where they have such parochial mindset. Harry had his office in a dilapidated but huge office in express estates. Harry was a thorough professional. He saw my portfolio and asked me :”Why do you have this camel in this picture ? I answered him for scale and perspective. I was very young just out of high school. He asked me am I willing to work as a photojournalist. i said yes, he quickly retorted with a sheet of paper requesting me do write my CV, I fished out my parter with turquoise ink and wrote in a beautiful scribe. He followed with a few questions on depth of field, optics and chemical compositions of developing and printing formulations. He use to smoke cigars. He was the only other chartered photograher there were just two of them those days in India. I am happy that Venkatraman did not take me in . I am blessed to have a far better life. I really do not how how life would have traversed with me if I had that job in Vizag, but the itch does stay to never go away.