Registered with the Registrar of Newspapers for India under R.N.I 53640/91

Vol. XXVII No. 22, March 1-15, 2018

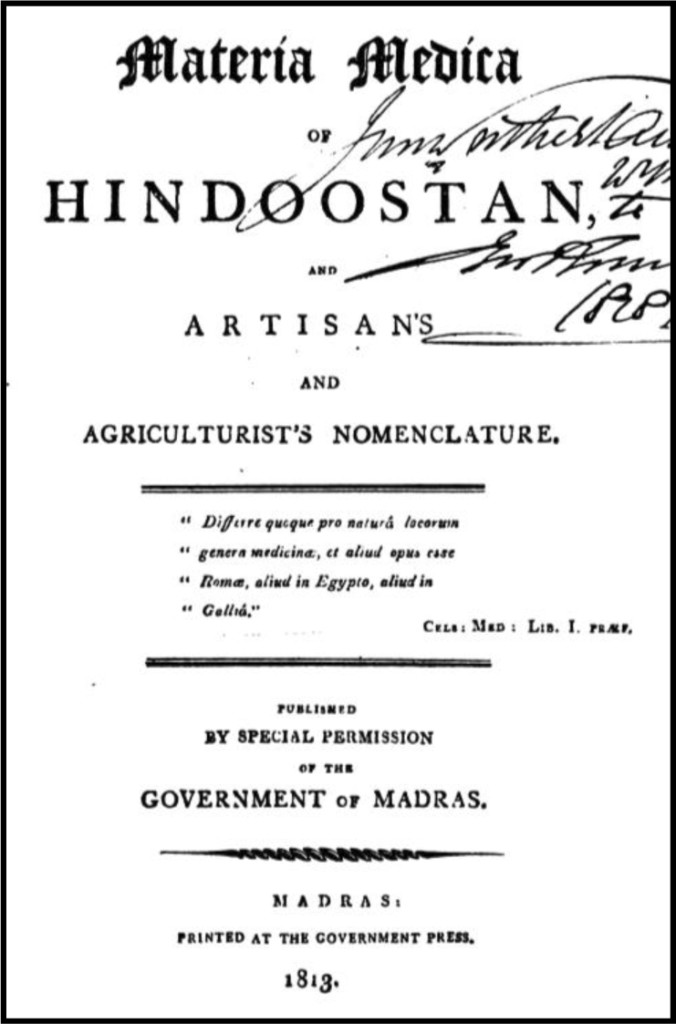

1813 medi-catalogue from Madras

by Dr. A. Raman (araman@csu.edu.au )

At a time when no materia medica – presented as an extensive pharmaceutical resource developed on the principles of Western science – existed in southern India, Materia Medica of Hindoostan and Artisan’s and Agriculturist’s Nomenclature was written by a Madras surgeon, Whitelaw Ainslie, and published in Madras in 1813. An enlarged edition of the same book titled Materia Medica, or Some Account of those Articles which are Employed by the Hindoos and other Eastern Nations in their Medicine, Arts, and Agriculture; Comprising also Formulae, with Practical Observations, names of Diseases in Various Eastern Languages, and a Copious List of Oriental Books Immediately Connected with General Science, &c. &c was published by Longman, Rees, Orme, Brown, and Green in London as two volumes in 1826.

Ainslie was born in Berwickshire (UK) in 1767. He joined the Madras Medical Establishment after qualifying as a Doctor of Medicine in Scotland. Initially posted as an assistant surgeon in Chingleput, he later worked in Trichinopoly as a superintending surgeon. In 1810, he catalogued the vegetables of India, planning to develop that catalogue as a medical treatise, which aimed at establishing a relationship among food patterns of Indians, climate, and the diseases that prevailed in India. He submitted this catalogue to the Council at Fort St. George.

He was appointed as the Superintending Surgeon of the Southern Army in Madras in 1814. He resigned the job in 1815 and returned to the UK, where he revised his 1813 Materia Medica volume, wrote on cholera in India, a literary piece (Clemenza or the Tuscan Orphan, 1822), and another on the introduction of Christianity in India (1835). He was knighted in 1839 in recognition of his revised edition of Materia Medica of India. He died in the UK in 1837.

In his catalogue, Ainslie remarks that some of the pulses and grains listed by him would thrive in sheltered situations in southern England, and recommended that experiments should be carried out (i.e. in UK) to grow them. The catalogue includes details under (1) corns and small grains, (2) garden stuffs, (3) large beans and small pulses (many of which have no English names), (4) roots, (5) fruits and nuts, (6) greens and teas, and (7) hot seeds, spices, seasoning agents, and oils. Each section provides the product’s native name, English name, botanical name (wherever known), and general remarks on, for example, value as food material or as material of medical use, and on cultivation.

Ainslie led a committee appointed by the Government of Madras to investigate the causes of the epidemic fever affecting the populations of Coimbatore, Madura, Dindigul, and Tinnevelly in the Madras Presidency. The report of this committee refers to malaria, which had been ravaging India for ages. Unknown as ‘malaria’ during the investigation time of the Ainslie Committee, the illness is referred to as ‘epidemic fever’ and was treated symptomatically.

The number of deaths in India due to malaria in the late 1800s and the first half of the 1900s is estimated at a little more than a million a year. In India alone, around the 1850s, the British Government was using nine tons of quinine annually. The point to be noted here is that Clements Markham brought Cinchona saplings from Peru to India only in 1869 and these saplings were subsequently established in the Government Botanical Garden in the Nilgiris.

Although the chemistry of Cinchona bark was characterised only in the 1820s, the importance of Cinchona bark in treating this deadly fever was known throughout the world in the later decades of the 18th Century. Obviously Cinchona bark was imported into India during Ainslie’s time in Madras. (Note: William Roxburgh, while stationed at Samulkottah Botanical Garden, found the bark of Swietenia febrifuga (Meliaceae) a potent substitute for Cinchona and, thus, a saving on the country’s exchequer.) Ainslie’s report frequently refers to using Cinchona bark in the treatment of the epidemic fever.

The 1813 edition of Materia Medica (about a quarter of the revised edition) printed at the Government Press, Madras, in 1813 outlined the purpose of the book:

“A catalogue, and an account, of such Medicines of the British Materia Medica, as are either the produce of Hindoostan, or are brought to it from Asiatic countries, and are to be met with in the Bazars of populous towns; including many Drugs of the Tamool, Arabian, and Persian Materia Medica; as also the names given by the Natives to different articles of diet, and other things for the comfort of sick; and the appellations bestowed on those materials which are employed in arts and manufactures: to which added, in the Tamool, Telingoo, Dukhanie, English, and Latin Languages, another and numerous Catalogue of the various productions of the Vegetable kingdom, which as used as food by the inhabitants of these provinces; and concluding with an Appendix, in which are contained the titles of Diseases in Tamool, Dukhanie, Telingoo, and English; together with a list of Malabar, Persian, Arabic, and Sanscrit medical work; a table of Doses and Weights, with the various forms of Prescriptions, &c. in use amongst the Indians.”

Ainslie dedicated this work to Johann Peter Rottler for his help in determining plants of India. Rottler (1749-1836), an Alsatian Lutheran Mission preacher and medical doctor, came to India following Johann Gerhard König of the Royal Danish Lutheran Mission (also known as the Tranquebar Mission and the Evangelical Lutheran Mission of Halle). Rottler will be remembered in 18-19th Century Madras for his contributions to the botany of southern India.

Ainslie’s volume has an English index, a Tamil index and a Latin index. The first index includes English equivalents wherever available, such as ‘spurge’ for a member of Euphorbiaceae, ‘gingelly oil’ for sesame oil (extracted from the seeds of Sesamum indicum, Pedaliaceae), and sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas, Convolvulaceae). This index also includes Tamil names of materials referred to in this text, which have been transliterated in Roman script with appropriate diacritical marks to relay the correct diction. The pages captioned the Latin index include biological names as known then.

Section I (Part I of the book) refers to chemical and biological materials that have been referred to in the British Materia Medica, but found in Asian countries and used by the Indian (medical) practitioners. It starts with a short description of sulphuric acid (referred as ‘Acid, Vitriolic’) with its Indian vernacular names mentioned either in transliterated Roman letters or in Tamil letters and its Latin name Acidum Sulphuricum. Details of its local production are explained: “by burning ‘some’ (no mass mentioned) sulphur with a small portion of saltpetre [KNO3] in a strong earthen vessel.” Ainslie adds, “… nearly in the same manner that we do,” implying the similarity in the production of sulphuric acid then in Britain.

His annotation on camphor from page 7 is an example of the details he supplies under each item he has listed. This section includes the biological name of camphor source, viz. Laurus camphora (now Cinnamomum camphora) (Lauraceae), which he indicates as growing wild in Japan. He refers to what was diagnosed by Indian physicians as Kistnah Doshum and equates it to Typhus fever1.

1 Typhus fever, the most common waterborne disease recognised in the 17th Century, was caused by microbial contamination from human faeces. Symptoms include high fever, weakness, headache, lack of appetite, stomach pains, and flat, pinkish spotty rashes. Typhus fever and Typhoid were differentiated in 1837. Edward Jenner presented a detailed comparison of the two diseases based on clinical and post-mortem appearances in 1850. Typhoid fever is caused by various strains of Salmonella, while Typhus is caused by various species of Rickettsia.

(To be concluded)