Registered with the Registrar of Newspapers for India under R.N.I 53640/91

Vol. XXVII No. 23, March 16-31, 2018

The beat of happiness

by Avis Viswanathan

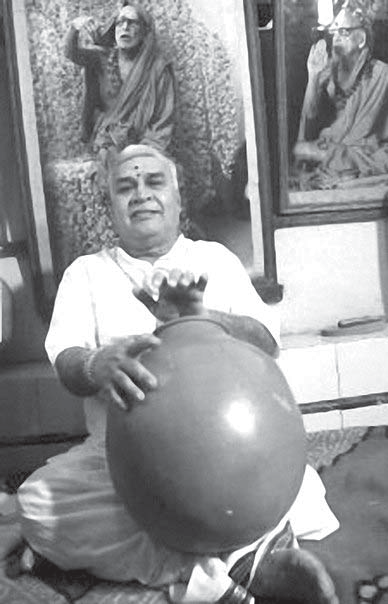

Vikku Vinayakram

Vikku Vinayakram’s home in Triplicane in Chennai has a sparse study-cum-meditation room on the second floor. Huge portraits of the seer of Kanchi – the Paramacharya or Maha Periyava – Sri Chandrasekharendra Saraswati (1594-1994), in different styles from posters to paintings to stained glass works, adorn the walls.

In the middle of the room, on a colourful jamakaalam sits a ghatam. It is a souvenir that a ghatam-maker gave Vikku. It has Vikku’s face carved out in the clay. He doesn’t like talking about that ghatam though. “The person who made this was overenthusiastic. Out of affection for him, I have retained this in my study. I had him make another one with Periyava’s image; that one is in my pooja room.”

The shelves and cupboard tops, and even some cartons, are full of awards that Vikku has received in his career of over 60 years as a performing artist. He wants to show my wife Vaani and me his Grammy memento – which he won in 1991 for playing for Planet Drum, an album by American percussionist Mickey Hart (who once was part of the band Grateful Dead); the award was for the Best World Music Album that year. But Vikku can’t find his Grammy memento among all his other awards. He manages to locate a plaque that all artists who played for Planet Drum signed on the occasion of winning the Grammy. What Vikku says when his search for the Grammy memento yields no result is deeply spiritual and awakening: “Parava illai! It’s okay! It’s here somewhere. For sure. What is important is that I enjoyed myself playing for Mickey Hart and with the other artists. The process of playing the ghatam, to me, overrides any recognition that I have got.”

Now, the man who is saying this is the world’s best ghatam player. In fact, he is credited with putting the humble instrument on the world music scene. He has accompanied the all-time greats of Carnatic music – Chembai Vaidyanatha Bhagavatar, M. Balamuralikrishna, GNB, Madurai Mani Iyer, Semmangudi Srinivasa Iyer, Ariyakudi Ramanuja Iyengar, Maharajapuram Santhanam and M.S. Subbulakshmi – to name but a few. And he has played with many Hindustani music stalwarts too – Hariprasad Chaurasia, Zakir Hussain, Shivkumar Sharma and Amjad Ali Khan, for example. More important, he is among those first artists from India who were bold enough to experiment playing world fusion music despite a very strong, conservative, classical orientation. In the 1970s, Vikku played with English guitarist John McLaughlin’s Shakti alongside Zakir Hussain (tabla), L. Shankar (violin) and Ramnad Raghavan (mridangam). And then, of course, came Mickey Hart’s Planet Drum – and the Grammy.

But Vikku is untouched by all this glory. As he sips filter coffee from a davara-tumbler, he nods his head furiously when I suggest to him that he must be very, very content with himself – what with a “lifetime in music and an era in greatness behind him”? “No, saar. Your question needs review. The ghatam has been around from the time of the Ramayana and Mahabharata. It is the only instrument that is made from the earth, from all the five elements – the panchabhoota-s. Who am I to take credit for making the ghatam famous or for all this glory that has come on account of it? I am most content playing good music with good people for good people to enjoy and energise themselves. I consider myself to be a postman, a messenger, a mere instrument for music to reach people. How can any instrument take credit for the music?” he asks.

To understand and celebrate Vikku’s humility better, his story must be told in some detail. Born along with his sister Seethamani, as a fraternal twin, Vikku’s original name was Ramaseshan. His father Harihara Sarma, a mridangam artist and teacher, was advised by the doctors that only one of the two children would survive; if both had to survive, said a soothsayer, one of them had to be given away in adoption. Sarma chose to give Ramaseshan in adoption to his favourite deity – Lord Vinayaka. And so the name Vinayakram came about!

Although Sarma lost one of his fingers in an accident, he taught young Vinayakram to play the ghatam by giving him beat-based instructions orally. Of course, the family’s income was meagre; so Sarma reckoned at first that having an artist with skills to play a different instrument (other than the mridangam) would bring in some additional cash. But sensing his son’s prodigal talent, Sarma laid out a vision that Vinayakram play the ghatam so well that the instrument would become famous across the world. “My grounding comes from my father’s vision. He did not urge me to play well for money or fame. He always taught me that music and the ghatam are much bigger than me,” reminisces Vikku.

The big break came when a 22-year-old Vinayakram was “accepted” by M.S. Subbulakshmi’s husband T. Sadasivam to accompany them on a US tour in 1964. This followed a concert of Semmangudi Srinivasa Iyer, who Vinayakram accompanied, at the Music Academy where both Subbulakshmi and Sadasivam were in the audience. Owing to the Indo-Pak war that intervened, the trip was postponed; but it eventually happened in 1966.

That was the first time any lead artist was willing to allow the ghatam as an accompaniment

on the world stage. That tour gave Vinayakram a feel of what it means to play music to a global audience. It was only M.S. Subbulakshmi who fondly called him “Vikku,” but since the nickname was easy on the tongue for the Westem audiences and artists, it soon became his identity globally!

“My father’s advice that music is divine, that it does not have boundaries and is not limited by styles and languages, resonated with me so much on that trip. Just the experience of performing with MS Amma was so transformational. The ghatam owes its gratitude to MS Amma for giving it a global stature,” he says.

Vikku has been very faithful to his father’s advice. He has always chosen music over anything else in life. In the mid-1970s, when he received an invitation from John Mclaughlin to perform with Shakti, he was on the verge of accepting a “permanent” job as an All India Radio (AIR) artist. Choosing the AIR job meant a steady income and job security. Going with Shakti meant short-term financial gains but infinite joy! Vikku chose joy. “I learnt the value of inner peace and joy from MS Amma and ‘Veena’ S. Balachander. Both of them told me, like my father always did, ‘Do only what gives you joy’. I simply followed their advice. Today, when I look back, I am glad I did what I did. I would have never been happy with anything but playing my music, my way,” he explains.

How has he managed to play in different cultures, with artists belonging to different genres, and to global audiences? Has he ever felt intimidated because of his very conservative background? Even as I take a while to phrase these questions, Vikku has his answer ready: “Music has no language. Zakir (Hussain) and I have a perfect harmony between us; when we are playing together we communicate with our eyes. When I played with Western artists like Mickey Hart or John McLaughlin, we never had any issues. They always respected my space, my beliefs and my music. And I respected theirs. Music unites; You don’t need anything else!”

Isn’t life as a musician, despite all the highs it offers, pretty unpredictable in a practical sense? The income is not consistent. And then there is age and the question of staying relevant in an ever-changing world. How does Vikku deal with these factors? His one-word answer is ‘faith’. He says you have to have faith that a higher energy will take care of you. To Vikku, that higher energy has always been the Kanchi Maha Periyava. “His grace is immense. It has guided me thus far and I have implicit faith that it will stay with me forever,” he says.

He shares an anecdote to amplify this point. Vikku was recently diagnosed with an eye condition that required neuro-surgery that would necessitate that he could not play the ghatam for at least 18 months. Vikku says, “I just could not accept the medical advice that I must not play the ghatam. I went into my pooja room and prayed to Maha Periyava. I left it to him. Then I went for my final, presurgery tests. And the tests came good! I would not need a surgery the doctor told me. Now, how do you explain this? Everyone is searching for God. I have seen God in human form – and that is Maha Periyava.”

As we get ready to leave, he adds this simple, yet so profound, perspective: “Nambikkai (faith) is the key to live happily. With faith comes nimmadi (inner peace). With inner peace comes anandam (happiness). I have always had total nambikkai. So even when worry arises or sadness comes, I invoke my faith. Desires ruin happiness. You can keep on desiring this and that and achieving this and that. As long as you are on this vicious cycle you will always be unhappy. Take life as it comes, with whatever it brings! Drop your desires and all you will be left with is anandanam-brahmanandam. Happiness – total bliss!”

As we stepped on to the street to find transport to take us home, I was for a long time looking at my Uber App without filling in any details. I was lost in my reverie. I was thinking, what kind of an evolved man he must be who does not really agonise that he cannot find his Grammy Award memento! To me, Vikku lives the philosophy of a desire-less state that he spoke about. And that is why he is so simple, grounded, happy and at peace with himself. Undoubtedly, he is a rock star in his own right, but one who is obsessed only with his music, and never with the trappings that rock-stardom brings along with it – the Grammy included. (Courtesy: Sruti).

This tribute is due to appear in the author’s book The Happiness Road. His earlier book was Fall Like a Rose Petal.