Registered with the Registrar of Newspapers for India under R.N.I 53640/91

Vol. XXVII No. 5, June 16-30, 2017

Nostalgia as History – 2

by Janaki Venkataraman

Pelathope Days

One of the most entertain-ing among this group of books is G. Ram Mohan’s Pelathope Days. Pelathope is a narrow residential street close to Kapaleeswarar temple in Mylapore and is said to be as old as the temple or even older. Today it looks more or less the same as a hundred years ago, except that it is far more congested. Pelathope gets its name from what was surmised to have been a grove (thoppu) of pala (jackfruit) trees before the grove made way for houses. Known to be a street full of lawyers, judges and doctors, Pelathope is a sort of microcosm of the world of Mylapore middle class life.

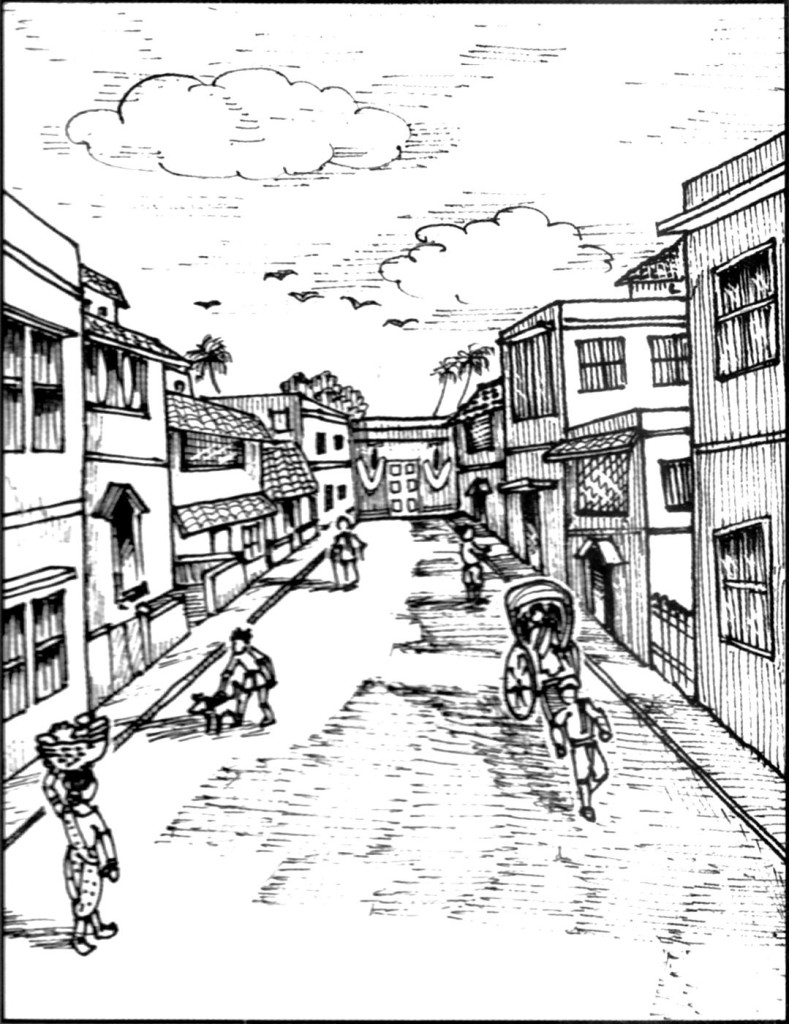

Ram Mohan moved into a house in Pelathope with his family when he was five and left the street only when he was 24. He writes, “The purpose of my writing this book is not one of recording the events of my life. I am well aware that it will not be a matter of interest to anyone. My purpose is to record such of my memories and impressions from my life as would give the reader an idea of what life was like in those days in a typical middle class Hindu family in Madras city.” And this he proceeds to do very well indeed, despite the fact that he writes entirely from memory. This simply produced paperback has charming line drawings that complement the chatty, humorous style.

Ram Mohan’s family were Telugu-speaking Brahmins and his father, G. Gopalakrishnan, was, what else, a lawyer. After living in various places in Mylapore earlier, and a short stint in Pudukkottai, where they headed when Madras was evacuated, the family moved into a rented home in Pelathope in 1942. They paid a rent of Rs. 40. The family was quite big, four boys and two girls. And as the normal family size in those days was four children, the parents and a couple of grandparents, there were plenty of children in the street for Ram Mohan and his siblings to play with. There was a lot of neighbourliness and loneliness was an unknown concept.

“We could see the Kapali temple tower from the first floor of our home in Pelathope,” Ram Mohan writes. “Now high rise buildings obstruct the view. The temple bells could be heard clearly during the three main pujas of the day… We were parallel to North Mada Street.” For a long time Mylapore consisted only of the four Mada Streets around the temple. Pelathope opens off Ramakrishna Mutt road which was earlier known as Brodie’s Road. The street ended in a dead end. All the houses were street houses, packed side by side, but each had its own distinct personality. Their only common feature was that the exterior walls were all lime washed in either white or yellow. The street was also earlier known as Vedanta Desikar Street and was associated with the festival honouring the Vaishnavite saint. Every year the idol of the saint was brought to Pelathope in procession, and the residents offered worship to the idol before it proceeded to the temple beyond Kapali Temple.

The junction where Pelathope meets Ramakrishna Mutt road is a shopping hive today. Ram Mohan writes that even in his time, the place was a commercial area, although not quite so crowded. “For many years, till about the late 1950s, it housed a popular Udipi style restaurant which we all referred to as simply Udipi Hotel. It was started by a Kannada family who were residents of Pelathope and they served the usual Udipi fare. The red building housed an eye clinic run by a Dr. R.N. Row. There was also a paan shop at the entrance to the hotel, owned by a Nair and so called Nair Kadai… Then there was a general merchant store at one end of the red building and a barber shop at the other end.”

“I still remember and can recall the prices of all items … we bought at the general merchant’s. The remarkable part is not that the prices were so low then. After all, incomes were also low and money’s value was much higher. The remarkable point is that the prices were so stable. During the first fifteen years or more of the period I have covered in this book, the prices and rates for all the items did not change one bit. The price of a cup of coffee in our Udipi hotel was two annas when we moved to Pelathope and about fourteen years later when decimal currency came into being, it was changed to thirteen paise. That was an increase of half a paisa, since the exact equivalent of two annas is twelve and a half paisas. All the Udipi style restaurants in Madras did it. People wrote angry letters against the ‘price rise’ to the editors of newspapers complaining that the hoteliers were exploiting the customers under the guise of changing over to decimal coinage. … I often wonder how the Finance Ministers of that era managed to keep inflation at zero level for years on end. Were there some wizards running the Finance Ministry? Or was it a natural outcome of the overall stability of society itself?”

Most of the shops mentioned by Ram Mohan have now disappeared. But Sathyam Studio, the photo shop and Murthy Pinmen, the laundry, remain there (at the time of writing, 2010).

All the children went to the same primary school. After that the boys went to P.S. High School and the girls to Lady Sivaswamy Iyer Girls’ School. The primary school might have had a name but as the elderly Brahmin running it had a long, flowing white beard, it was popularly known only as Dhaadi School. It crammed 50 kids to a class, which had only benches to sit on and no desks and the children wrote on slates held against their bellies. The medium of instruction was Tamil until Form 4. Emphasis was placed on oral learning and committing to memory, whether the children learnt the maxims of Avvaiyar or mathematical tables. “We were trained to do lots of problems by mental arithmetic,” Ram Mohan writes. “A typical problem in mental arithmetic set for a fourth standard student would be something like this: ‘If 15 palams of sugar costs six annas and nine pies how much would a veesai cost?’ Forty Palams were a veesai, twelve paisas an anna and sixteen annas a rupee. We did it mentally and arrived at the right answer as one rupee two annas.”

There were tables up to sixteen to be learnt normally and then by reverse. There were also the fraction tables – for three-quarters, half, quarter, one-eighth and one-sixteenth upto one-sixty fourth. “In those days I could tell you at a pinch that a hundred times one-sixteenth is six and a quarter and seven hundred times one-eighths is eighty seven and a half,” Ram Mohan recalls proudly.

Life in Dhaadi School also exposed the children to the poverty of other children who could not afford to pay even the meagre fees and were malnourished, as well as to the dark side of schooling, corporal punishment and poorly paid teachers.

Ram Mohan’s father later bought the house they rented. Firewood was the primary fuel used for cooking. So every house had a ‘lumber room’ where the firewood was stacked. The wood attracted scorpions which now and then dropped down. “Their sting was extremely painful. They were slow movers and when one was sighted there would be an alarm raised. It was the duty of any adult male present to beat it to death with the nearest available weapon – usually a stick or a piece of firewood. There was an occasion when Chandi (my elder brother) was the one who sighted a scorpion. ‘Scorpion! Scorpion!’ he screamed. ‘Call some man!’ He was 21 then!”

There is a chapter dedicated to the kudumi (tuft) and the urgency to get rid of it in an Anglicised world. Ram Mohan’s maternal grandfather loved his kudumi but was forced to get rid of it after it began to embarrass him in front of his British bosses. As a matter of courtesy, he had to, in their presence, remove the tightly starched and tied turban within which he concealed his kudumi. The moment he did that, his kudumi would come cascading down.

Then there is the story told about the kudumi of the famous cricketer, M.J. Gopalan. “I can’t vouch for its truth: but it is an interesting story,” writes Ram Mohan. Gopalan, from an orthodox Ayyangar family of Triplicane, sported a big kudumi. “He would conveniently tuck his kudumi under his solar hat when batting or fielding; but trouble came when he bowled. He had to necessarily remove his hat to bowl. The exposed kudumi proved to be his undoing. When he was selected to play against a touring England team in the 1930s, the English batsmen initially found his bowling unplayable… then one batsman found a way out of the problem. When Gopalan bent his bowling arm sharply at the shoulder (to bowl his ‘mystery’ delivery) that sharply bent arm would expose his kudumi and cause it to drop and unfurl. That was too obvious a sign for the batsman to miss and Gopalan lost his vital surprise element… “Take off the tuft Gopala, and I will take you in the test team,” Vizzy (the captain) is said to have told Gopalan.

“Gopalan refused and was dropped from the test team after being given just one chance.”

The book recounts how festivals were celebrated in Pelathope and how socially complicated weddings were, how women slowly came out of stifling protectionism and got educated, how rooted the children were in their own cultures while at the same time trying to understand the rest of the world through magazines and books; of the ten-day Kapali temple festival (that was banned for six years from 1940 to 1945 on account of World War II. It was considered a security risk as the bright lights of the nightly festivities could attract air raids). Ram Mohan talks of the stifling orthodox practices of the households, the superstitions that ruled their lives, street cricket and the excitement of going to Chepauk for the real matches, and of the warmth and joy of growing up in a big joint family. “I am no psychologist but I strongly believe this: growing up in a home with a large number of sisters and brothers, and interacting with boy and girl cousins, gives a youngster, boy or girl, a much healthier attitude towards the opposite sex from early on in life. Boys in those days, I feel, imbibed a sense of respect for femininity from early on.”

Pelathope Days is nostalgia at its best and most entertaining. (Published by Akshaya Publications, Alwarpet.)

e-mail: visalam.rammohan@ gmail.com

Privileged to record that my brother S Karpagavinayagam and Sri Ram mohan were contemoraries in Guindy Engineering College,during 1954 -’58.By God’s grace their frienndship continues.Sri Ram mohan served Indian Railways,in senior positions,with distinction.I was in Railway Service,as well.Have read the book under review,with great relish.Truly,a slice of Madras History of 1940s,’ 50s and early sixties.