Registered with the Registrar of Newspapers for India under R.N.I 53640/91

Vol. XXVII No. 6, July 1-15, 2017

The Mittaikaran of Madras

by N.S. Parthasarathy

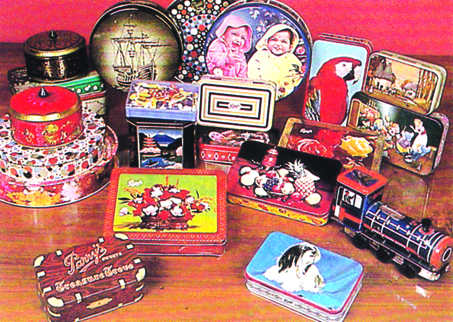

Parrys’ sweet tins over the ages

For anything we wish to buy today there is a vast range of brands to choose from, promoted through multi-media advertising blitzes. But, once, there were products that commanded the respect and choice of consumers although they were not blitzed as a brand; one of these was Parry’s Sweets, the term used as a double-barrel proper noun and, therefore, referred to in singular. It commanded recognition among children and adults alike throughout the country. This Madras Province product wore, at one time, an aura rivalling those of ruling international brands for consumer products.

If you had then asked what Madras was known for, it is highly likely that Parry’s Sweets would have been one of the items. School textbooks on Social Studies never failed to mention the second largest sugar factory (sarkkarai aalai) in the country – ranked so at that time – at Nellikuppam and the confectionery factory making sweets (mittaai gedangu). Some texts referred to it by name as paari mittai! School children were thrilled to be taken on a conducted tour of the factory, particularly as they were given samples to taste and take home. This was practically the only public relations exercise till, in later years, formal advertising campaigns were launched on meagre budgets by current standards.

* * *

The chord line train in the 1950s stopped reluctantly at Nellikuppam and you could, seated in the train, inhale the fresh boiling sugar syrup waft emanating from the confectionery unit. The confectionery unit was headed by an Englishman, Harry Donovan, an expert confectioner who was succeeded by his understudy, George Inglis. They were not university graduates but had outstanding skills and were perhaps the best confectionery technologists in the country. What they made, innovating new varieties all the time, set the standard for the rest of the manufacturers in the market.

The Parrys’ factory at Nellikuppam

Donovan’s genius was reflected in the large range of sweets, over a hundred items, unrivalled in the market for the variety of flavours and packaging. There were hard boiled sweets, boiled pulled sweets, toffees, marshmallows, jujubes like jelly in different colours coated with shiny crystal sugar (referred to technically as gum and gelatine sweets), almond centres, sugared nuts, throat pastilles, pan rolled varieties like gems in a flush of colours, the very popular lemon and orange slices authentically shaped and coloured to imitate the real slices, extra strong mints, bull’s eyes etc. Gift tin containers for festivals, printed gorgeously with contextual themes, were very popular. Most of the varieties were packed in lacquered 7-pound tins sealed air-tight with soldered tin taggers, sixteen of them in each stackable wooden case. The price was per hundred weight, cwt in short, equivalent to 112 lbs (about 50 kilos).

Confectionery, being basically a food product, marketing presented quite a few challenges. What is made had to be sold and consumed before quality was affected. Ahmed Mohideen, who joined the company in the mid-1930s, as senior assistant to the English Manager at the Head Office, played a significant part in masterminding the marketing strategy, designing and building the national distribution network, and formulating sales policies. These evolved out of the product and consumer buying characteristics.

Exposed to air, boiled sweets oxidise, become sticky and could become unpalatable and sometimes harmful for consumption. The shelf-life is limited. A very large proportion of sweets bought by a consumer was not in large quantities packed in sealed containers but in ones and twos against small coins. The product had to be produced, stored and distributed to final outlets just in time for consumption and this had to be repeated at a frequency that ensured that sweets in the retailer’s jar were not older than two weeks.

The special needs and characteristics of the product determined the design of the distribution network and selling policies. A three-tiered distribution network was set up on a national scale over a period of time. The network comprised wholesale warehousing firms at major centres, distributors in every town serviced by the nearest wholesaler, and innumerable retailers drawing bi-weekly requirements from the distributor in the locality. The hallmark of the system was that the product at retail points was always recently delivered fresh stock.

Price of sugar, the main ingredient, was subject to variation, affecting the price of confectionery. If wholesalers and distributors suffered loss having to sell their stock at lower prices, whenever sugar prices fell, they were offering reimbursement of the difference in price provided the stock had been bought not earlier than eight weeks.

As sweets were generally sold in ones and twos, careful attention was necessary in determining the size and price of new varieties. Each piece has to be sold for a round unit of coin. Lower priced ones for a smaller coin and the better ones for a larger unit of coin. Even thus sold, the retailer has to be able to make a handsome margin of 20-25 per cent.

Such intricacies shaped by Mohideen set the trend for the confectionery industry. He established the product as the market leader for pricing as well as practices. Morton and Ravalgaon dominated the market in the North, but had to contend with Parry’s Sweets from the South. Nutrine emerged in the South as a competitor after securing the services of a senior confectionery technologist from Nellikuppam and competed through lower prices. Mohideen, not wanting to undersell a prestigious brand, innovated ‘Deccan Sweets’, to sell at lower prices. He called it the “fighting brand”.

Mohideen served Parry’s for thirty years of which his association with confectionery was for over 20 years. He became President of the Indian Confectionery Manufacturers’ Association.

Mohideen who had a Master’s degree in Philosophy, wrote books on fiction, poetry, drama and philosophy after retirement. His book on Islam for children is worth reading also by adults unfamiliar with the message of this religion. He had friends across the religious divide – which fact, unfortunately, needs special mention these days but was assumed as normal in his time. In retirement, his advice was sought by Hamdard products.

He was from a family that descended through one branch of the Muhammad Ali Wallajah, Nawab of Carnatic (1749-1795) family and married into a family that descended through another branch, his wife being the first cousin of the seventh Prince of Arcot. Her father pre-deceased his younger brother to miss becoming the sixth Prince of Arcot.

Senior colleagues and Mohideen used to go together for lunch to the Company’s lunch room reserved for seniors, and when, at times, he could not join them in time, his friends asked jocularly: Where is the mittaikkaran? Ahmed Mohideen was indeed the Mittaikkaran of Madras.

(The writer worked in the confectionery factory and the controlling office in Madras, for five years, 1952-56)

Comments