Registered with the Registrar of Newspapers for India under R.N.I 53640/91

Vol. XXVIII No. 1, April 16-30, 2018

Sriharikota days

R.V. Rajan rvrajan42@gmail.com

A personal history by R. Aravamudan with Gita Aravamudan

Tales out of the ISRO Story

(Continued from last fortnight)

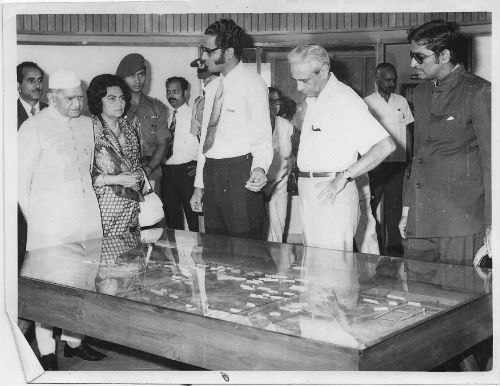

Aravamudan explaining the Thumbha lay-out to the then (mid-1970s) President, Fakruddin Ali Ahmed.

Satish Dhawan is to Aravamudan’s left.

Dr. Sarabhai was a handsome man, a brilliant and charismatic person with a fantastic memory. He never bothered about the usual social formalities and was easily approachable. He always wore white khadi kurta pyjamas paired with well-worn Kolhapuri chappals. He never carried a wallet and always turned to his PA or some other aide, if he needed money. Only on very special occasions would he be dressed in a formal dark brown bandhgala coat worn over pants. Inspired by Dr.Sarabhai even the scientists at ISRO took to casual bush shirts and pants. He had the gift of making each person feel very important and wanted. He listened to whatever proposals were presented to him with total attention and encouraged the scientists to experiment.

During a visit to Thumba, on December 29, 1971 Sarabhai died of a cardiac arrest in the hotel room where he was staying. Government decided to appoint Professor Satish Dhawan to succeed Sarabhai.

While Sarabhai’s style of management was that of a patriarch dealing with a small, well-knit family, with no formal systems in place, Dhawan’s style of management was quite businesslike. He followed the HQ type of structure by hiring management educated and experienced young men as shadow teams. They would function from the HQ and make a technical and budgetary analysis of each programme.

The change in style was difficult for the original team to deal with at first. Soon they realised that this kind of change was inevitable, given the increasing complexity of the projects and the size of the budgets involved. Dhawan was very particular that local industry and academia should be associated with the programmes. Under the “Respond programme” small grants were given to various research organisations to undertake specific projects for space research. Though ISRO as an entity was formed just before the passing away of Sarabhai, the ISRO we know today began to take shape only after Dhawan took charge. Under him four distinct geographical areas emerged: Trivandrum, Bangalore, Sriharikota and Ahmedabad.

* * *

Dan led the team that developed the ‘C’ band tracking radar installed in Sriharikota. This radar was the first indigenously built one. TIFR, Bhabha Atomic Research Centre (BARC) and Electronic Corporation of India Limited (ECIL) partnered with the ISRO team for this project. By 1979, the radar facility at SHAR, Sriharikota, was ready, well in time for the launch of the country’s first indigenous space vehicle SLV-3. Kalam was in charge of the launch. After the failure of the first effort, a second attempt was made.

Old friends – Aravamudan and Gita with Abdul Kalam at Rashtrapathi Bhavan (2007).

Dan says, “The second launch effort also had its moment of nail-biting suspense. A few moments prior to take-off, the command was given to detach the umbilical cable from the rocket. However, the remote controlled cable just refused to come off. For a few moments no one knew what to do. Obviously the launch could not take place with a stuck cable. The saviour of the day was a technician named Bapiah. He volunteered to climb up the launch tower and manually coax the cable off. The tower was around 60 ft high. We had no other option but to let him try with the safety officials turning their back for the short while. Bapiah quickly climbed the tower and gave the cable a hefty kick and it mercifully came off. The rest, of course, is history. And so on July 18, 1980, almost 17 years after the first foreign Nike-Apache sounding rocket was launched from TERLS, a made-in-India rocket was launched from Indian soil, injected an Indian made satellite into a 300 km by 900 km orbit. It was an ecstatic moment. Kalam was hoisted on the shoulders by his colleagues. In Trivandrum we were all welcomed as heroes when we stepped off the plane. My little sons were thrilled. In their school the SLV had been dubbed as the Sea Loving Vehicle. And now their father’s organisation had been vindicated.”

Significantly, out of the 1200 scientists and engineers who worked on the SLV 3 project, hardly a handful had had a foreign education. Our homegrown engineers were the ones who built our first satellite launch vehicle.

* * *

When Dan became the Director of SHAR in October 1989, his family moved with him to Sriharikota. His elder son was at Bangalore to join an engineering college and the younger son joined the SHAR Central School. Dan says, ‘SHAR was a total contrast to Trivandrum. It was home to a rather insular space community that lived in peaceful isolation far from the madding crowd. Surrounded by Pulicat lake, the Bay of Bengal and Buckingham Canal, Sriharikota was an island with a 50 km coastline and area of about 44,000 acres. There were thousands of employees, temporary and permanent living in the housing colonies. And I was the Big Boss. My friends and colleagues dubbed me the ‘Sultan of SHAR’, although I must confess I sometimes felt more like the Count of Monte Cristo imprisoned on an island.’

Sriharikota had a population exceeding 10,000 and hence all the civic amenities had to be provided by ISRO. As the Director-in-Charge in running the township, in addition to his professional responsibilities Dan also felt like a Municipal Chairman. The first experimental launch of PSLV happened on September 20, 1993 when Dan was still the Director of SHAR. U.R. Rao was the then ISRO Chairman and Madhavan Nair was Mission Director. While all the initial events which were visible seemed to have been taken at the right time up to the second stage, the vehicle suddenly went into dramatic uncontrolled angular rotation. The first launch of PSLV vehicle had failed.

It took more than a year for ISRO to recover from the failure of the first launch. In the interim period Dan moved to Bangalore as the Director of the ISRO Satellite Centre (ISAC) and Kasturirangan took over as the Chairman of ISRO from U.R. Rao. Kasturirangan turned out to be a lucky mascot for ISRO; his first mission as ISRO chairman was a thumping success. Madhavan Nair, the PSLV Project Director, was the man of the hour. The launch was an example of perfect coordination between a variety of agencies in India and abroad focusing on a single objective. Our own home-grown PSLV became one of the most reliable rockets in its category in the world, earning global admiration. Nations vied with one another to get their remote sensing satellites launched by it; and ISRO never looked back

* * *

The next ambitious rocket that ISRO was to launch was the Geosynchronous Launch Vehicle (GSLV) which revolved around the development of a cryogenic upper stage and ISRO had to struggle hard against all kinds of political and other stumbling blocks placed by the USA and Russia, before the launch became a reality on March 28, 2001. By this time Dan had retired and was not at a console but seated in the VIP gallery. Dan says, “I had grown with ISRO from the days when it was a mere idea in a visionary’s mind through its phenomenal transformation in more than half a century into the veritable giant it has become today. Although I formally retired from ISRO in 1997, my close, almost umbilical connection with the organisation can never be severed. I still sit in on important reviews and meetings and continue to keep track of all the developments; we are nowhere near the end of the story. ISRO has many more exciting milestones to cross in the years to come.”

Harper Collins, 2017.

(Concluded)