Registered with the Registrar of Newspapers for India under R.N.I 53640/91

Vol. XXIX No. 9, August 16-31, 2019

Appointments and Disappointments – memories of Tamil Nadu’s legendary DGP

by Karthik Bhatt

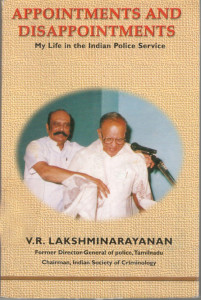

The cover of V.R. Lakshminarayanan’s memoirs Appointments and Disappointments.

The cover of V.R. Lakshminarayanan’s memoirs Appointments and Disappointments.IPS officer V.R. Lakshminarayanan passed away recently. Joining the service in 1951, he rose to become the DGP of the State in 1985, appointed to the post by M.G. Ramachandran from his hospital bed in New York. It was the pinnacle of a glittering and eventful career at both the State and National levels. V.R. Lakshminarayanan’s memoirs ‘Appointments and Disappointments’ is a fascinating account of his life in the service.

He hailed from a family of lawyers. His father Rama Ayyar had a princely and extensive practice that covered Malabar, the South Canara Districts and Mysore State. Rama Ayyar’s eldest son V.R. Krishna Iyer joined him in practice in 1937 and was on his way to becoming one of the country’s finest legal minds. It was hence expected that Lakshminarayanan too would join the family practice once he qualified for the Bar. However, driven by “a passionate and platonic idealism to serve the public, to stand on one’s own feet, the glamour of being a member of a premier class I service and the lure of the uniform” as he puts it, he went on to appear for the All India Services exams and passed with flying colours in 1951.

On completing the first phase of training at Mount Abu, Lakshminarayanan was posted to Madurai for practical training. Recounting his first day as a police officer in the State, he mentions his first visit to the imposing Office of the Inspector-General of Police on the Marina (now the Office of the DGP), which he describes as “a most beautiful and well-manicured building, by all means the most splendid police office anywhere in the world”, with “the aura and charm of an ancient castle of a bygone age’”. (His fascination for the building would last till the end of his life – in a late 2018 interview with this writer, he recounted how he rushed to the premises to check on the state of the building on the day of the tsunami!). Following the training at Madurai, he was posted to Chingleput as Assistant Superintendent of Police and thus began his illustrious journey.

In his career, Lakshminarayanan had several stints at the national level. His first one was in 1954, when he was sent on deputation to the Intelligence Bureau in Delhi. A few years later, he was posted in the Special Police Establishment where he became ‘one of the midwives’ of the Central Bureau of Investigation which was setup in 1963. His tenure with the CBI lasted for seventeen years and would see him rise almost to the top rank. Following the reorganisation of the Bureau and the subsequent creation of the Economic Offences Wing, he was appointed its Deputy Inspector General.

His biggest moment on the national stage came during his stint at the Central Bureau of Investigation, where, as its Joint Director in 1977, he executed the arrest of Indira Gandhi in a corruption case. He describes the event as being “an unedifying feat” and probably considered it somewhat ironic as he had previously received two medals from her for meritorious service. Recalling the incident, Lakshminarayanan says that he had insisted that no handcuffs be used, though the former Prime Minister had asked him as to where they were. She had also been allowed to take along her personal attendant as matter of courtesy.

However, the return of the Congress government in 1980 saw several changes in the corridors of power, and the CBI was no exception. The top post would elude Lakshminarayanan, who returned to Tamil Nadu as the Inspector-General of Police, Planning. This would mark the beginning of his ascent to the top post of DGP five years later.

Lakshminarayanan considered his stint with the Tamil Nadu Police Housing Corporation as one of the most satisfying ones in his career, as it presented him with the opportunity to help the constabulary. The organisation was setup in 1981 to build houses for retired and retiring policemen. The project was the first of its kind in the country when he was appointed its Managing Director and later, Chairman. Its first project, the construction of around 800 houses with bio-gas facilities in Trichy, was completed at a commendably low cost of approx. Rs.75 per square feet and paved the way for several successful ventures in the future. Several interesting anecdotes pepper the narrative in Lakshminarayanan’s memoirs. Written with a fine sense of humour, charmingly self-deprecatory at times, they bring to light the varied circumstances and challenges that face public servants in the line of duty. One amusing incident worth recounting is the way the bundobust was handled when the Dalai Lama and the Panchen Lama, the spiritual and secular heads of Tibet respectively, visited Madras at the same time as guests of the Government of India. The dictum was that they had to be treated absolutely the same, though they lived under separate roofs. With their respective followers on the lookout for any favoured attention to the other, in addition to China watching out for any offense to their ‘Marxist protégé’ (the Panchen Lama), it was a diplomatic disaster waiting to happen, one that he says would have advanced the “Border war by a few years”.

Lakshminarayanan’s tenure as DGP began in January 1985. Though it was a short one, it was marked by several internal and external initiatives aimed at creating a better work environment. He strongly believed that a Police Chief had to be a Public Relations Expert, as it was the public’s goodwill that was their biggest strength. He organised initiatives such as police-public sport meets to build rapport with the public. He also addressed several gatherings, including students, in a manner empathetic to their difficulties. He was accessible to every officer and saw to it that their grievances were redressed by him to the greatest extent possible. Even after retirement, he continued to mentor several policemen.

His passing truly marks the end of an era.