Registered with the Registrar of Newspapers for India under R.N.I 53640/91

Vol. XXX No. 20, February 16-28, 2021

Lost Landmarks of Chennai

- Sriram V

More on the Madras Glass Works

A report from Vivekabodhini.

As it so often happens, some further details on the Madras Glass Works surfaced after the previous article on it (see MM, Feb 1, 2021 Lost Landmarks) was published. Karthik Bhatt sent me the June 1910 edition of the magazine Vivekabodhini which not only had a detailed report on how the factory operated but also a photograph of the crucible where the molten glass was made. The writeup, in old world Tamil is not easy to translate and goes into too many details to sustain present day readership’s interest. But certain aspects do merit attention.

Firstly, the location. Quite contrary to what was surmised in the previous edition of this column, the Madras Glass Works was not in North Madras but very much in centre of the city – it was by the Ice House, facing Beach Road/Kamarajar Salai. This may have been almost at the same location where the Lady Willingdon School stands today. The article states that the principal drain of Triplicane emptied by the Glass Works.

That brings us to the second question – why this location? The answer is in the Vivekabodhini article itself. The Glass Works needed sand in abundant measure, apart from seashells, caustic soda and timber. The first of these came from a special quarry in Ennore that had been allotted to the company. This had to be transported to the place of manufacture of glass and the consignments came by boats plying on the Buckingham Canal. Timber arrived via the same canal, chiefly from casuarina groves south of the city. This was probably stored at the Old Firewood Bankshall (see Lost Landmarks, Vol. XXIX No. 21 , February 16-29, 2020) which was just south of the Glass Works. The Governor of Madras Sir Arthur Lawley had according to the Vivekabodhini visited the factory and by way of encouraging the new enterprise had sanctioned the supply of Rs 75,000 worth of timber free of cost. This it will be recalled from the earlier episode, was founder Scholl’s parting gift to the company. The seashells were available in plenty on the beach and were probably collected from all along the shoreline. Only caustic soda had to be imported. The proportions in which the sand, the caustic soda and the powdered lime from shells were mixed remained a proprietary secret.

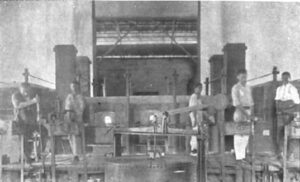

A view of the Madras Glass Works.

The Vivekabodhini report on the Glass Works gives us a picture of a very self-contained facility. The Director’s cabin was first on entering from the east and had apart from a standing display of all products made at the works, a door that led to the finished goods warehouse. The facility churned out not just soda bottles, though these clearly formed the bulk. A full catalogue reveals bottles of two standard sizes, wide and narrow jars, mirrors and glass tiles – of the ground and transparent varieties, these being much in demand then as skylights on tiled roofs.

The sand was what greeted the eye first and this was spread out and cleaned on a specially constructed lime and mortar platform. The star attraction at the Glass Works however was clearly the crucible where the mix was actually melted and the article describes it in great detail. Fronted by an enamel panel, the furnace had an intriguing arrangement to conserve coal, which was the primary source of fuel. Once lit, this in turn heated up the timber, that was placed above and separated from it by means of a sieve-like plate. The logs of wood did not burn directly but in the intense heat let out gases which were in turn tapped by flues and led back to the furnace where they supplemented the coal fire. The reporter who visited the works states that this ensured uniform spread of heat which meant that the silica in the sand melted uniformly as well. It also minimized the consumption of coal.

Unlike the continuous and hugely automated processes of today, the simple techniques of the time make for quaint reading. The furnace at the Glass Works was not fired continuously. Made of limestone, it was the size of a room, with six windows, three on the east and three to the west. These were opened and closed to control the temperature in the furnace. The mix to prepare glass was placed in this crucible each evening and the furnace lit. The fire burnt through the night and by the next morning, molten glass was available to be tapped. The process of moulding the bottles was however entirely manual and the description of it, though tedious, is clear that it involved the workers using their hands, feet and mouth. At the end of the drawing and moulding, the entire bottle emerged, complete with a glass ball in its neck. The description is probably the first in India of the manufacture of the codd-necked bottle, better known as goli soda in colloquial terms. Each bottle was stamped with the date of manufacture and cooled over a long period of time – this lasting several days at times. There was hardly any wastage, for bottles that broke were simply tossed back into the mix where they were melted.

The tile-making process was not much different except that this did not involve moulding. The glass was cut and then if needed to be ground, subject to sandblasting. This process was mechanized and then the tile, whether transparent or translucent, was beveled at the edges. The grinding generated quite some heat and this was vented out by way of a chimney. Though the catalogue mentions mirrors, it is clear that the process of silvering was not done here and it is likely that the glass was sold to specialized mirror makers who handled that process. There were plans to add other products and the article states that a team of technicians from overseas was on its way to train the local labour on the processes.

There is an interesting comparison given on how the locally made glass compared with the imported variety. A gross (144 nos) of the large soda bottles cost Rs 13/As 8, while the same if imported cost Rs 18. The small-sized bottles cost Rs 11/As 4 while those from abroad cost Rs. 15. The tile if clear cost Rs. 1/As 8 and if ground Rs. 1/As 12 while the imported equivalents cost a whopping Rs. 3/As 12 and Rs. 4/As 4 respectively. The locally made bottles withstood pressure of 450 psi while those from overseas did not go beyond 225 psi. The production figures were also impressive – a bottle emerged every two minutes but it must be remembered that there was only one shift of 12 hours.

The article ends with a prayer that the Glass Works ought to be successful and give gainful employment to many Indians. That sadly was not to be, for as we know it folded within a year. But what this venture, and several others begun at this time did prove was that Indians were as good as any European in managing a commercial enterprise. In that sense its impact was enormous and slowly but steadily Indians began getting into business. Today, if India is considered an industrial economy, it is small beginnings such as the Madras Glass Works that showed the way.