Registered with the Registrar of Newspapers for India under R.N.I 53640/91

Vol. XXX No. 22, March 16-31, 2021

SOPs for Elections, since 1957

by Karthik Bhatt

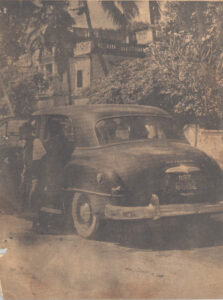

Voters being ferried in a party car – 1957.

Our State goes to polls on the 6th of April. The campaigning, which began much in advance has gained momentum with top national leaders visiting the State multiple times, with more visits being scheduled in the coming weeks. The Election Commission has intensified checks across the State to prevent distribution of bribes, either in cash or in kind. Allegations and counter-allegations have flown thick and fast, with promise of more to come. With the battle reaching fever pitch and less than a month to go, this article is a recount of how the 1957 Parliamentary elections were fought in Madras as narrated in the Swatantra magazine.

A national leader campaigns

The elections were held in Feb-March 1957. The battle for the South Madras Parliamentary Constituency saw T.T. Krishnamachari contesting the polls on behalf of the Congress. One of his opponents, contesting as an Independent candidate was the firebrand freedom fighter and entrepreneur H.D. Rajah. Jawaharlal Nehru campaigned for his colleague T.T. Krishnamachari and launched a scathing attack on Rajah, who during his campaign had quoted the names of Mahatma Gandhi and other famous personalities of the past who had said kind things about him. The report comes down heavily on Nehru for his statement, which it said had not contested the veracity of the statements made by the personalities but had instead questioned the right of non-Congressmen such as Rajah to use hallowed names to their benefit, thereby giving rise to a serious contention that ‘the personalities of Mahatma Gandhi and other national leaders were exclusive property of the Congress party’. It also took umbrage at the timing of Nehru’s statement, coming as it did ‘just as the voter was on his way to the polling booth and looked like the exercise of force which was unbecoming of a national leader’.

Brazen violation of law

The magazine carried a photograph of a car that was used for transporting voters to their polling booths on its cover. This practice had apparently been common in earlier times when the law was not so strict but certain subsequent changes had made such acts illegal. The magazine reports that there were “under a modest estimation about one thousand cars plying on that day in Madras city, ferrying the voters across from their homes to the booths and back with the public looking on with amazement at this open transgression’’. It noted that when the changes to the law strictly prohibited use of vehicles to stimulate voting, with even the voter who obliges a friend and gives him a lift in his car to the polling booth being liable to be penalised, it was shocking to see such open defiance of the law and called for a public inquiry into the matter.

Missing Voters

The most common complaint in any election today is that of names of voters missing from the electoral lists. This seems to have been the case even six decades ago. The magazine however reports grave irregularities in the printing and distribution of the several voter lists by the Government with the explanations given to reconcile the discrepancies not being convincing enough. One common reason given, the report notes, was that the lists were bound to suffer from the printer’s devil as they had been printed at different places. Another explanation was that amendments had been made to the lists after they had been printed, which had been issued as annexures that had not been bound with every list, thereby making them untraceable. The magazine, while recognising that it was quite conceivable that such common mistakes could happen, the fact that an amazingly large number of voters of one particular candidate seemed to be turned away from the booths while practically none of the voters of a certain other candidate encountered any such difficulty was definitely ground for suspicion.

Processions and free cinema shows

The magazine also draws attention to the ‘deluxe propaganda’ of free cinema shows being organised and the gala processions illuminated with fluorescent lamps led through the streets by candidates who could not afford such luxury. Each of the processions, it says would have cost ‘several thousands of rupees every night’ because of the illuminations involved and the use of mobile generating sets for electricity. It feared that these expenses would never be included in candidates’ returns of election expenses as they would swell the figures beyond the permitted maximum and would instead be explained as voluntary contributions by friends and well-wishers. ‘It would be interesting to know who these friends and well-wishers are who squandered away their fortunes in such a worthy cause’, it adds pithily.

Perhaps the most scathing comment that sadly continues to hold good even today is that of use of money power to influence the outcome. ‘Corruption was the order of the day during the polling’, it notes adding that ‘this cannot be prevented in the current set-up, for when money flows like water amidst an impoverished population, you cannot blame the people for selling their votes which are otherwise of no value to them’. It also alleges that the lax watch over the polling booths, which enabled voters to pocket their vote instead of depositing in the boxes led to the formation of a black market, where the smuggled votes commanded a high price.

In conclusion, the report notes that the elections were decided by the weight of money power supported by what it says was euphemistically called ‘influence’. It also notes the nexus between political parties and businesses and the role played by businessmen to ensure they did not lose the goodwill of the candidates, what in today’s political discourse is referred to as crony-capitalism. This, it says was the reason why ‘so many prominent men in the business world who seldom interfere in politics put themselves out during the elections and made themselves prominent on the polling day’, adding that this had rendered the election a farce.

It is perhaps important to recognise the context in which this report appeared. The Swatantra magazine was started in 1946 and run by Khasa Subba Rau, a firebrand nationalist who had taken part in the freedom movement drawn by Mahatma Gandhi’s ideals. He was a man of lofty principles who never hesitated to take on those in power and speak out the truth. In particular, he often took on Jawaharlal Nehru whose policies were regularly lambasted over ills such as corruption, nepotism and selfishness. Subba Rau was perceived to be close to C. Rajagopalachari, with whose blessings he started the Swarajya magazine in July 1956 after shutting down the Swatantra. Rajagopalachari had resigned from the Congress in early 1957 and had founded the Congress Reform Committee (later renamed the Indian National Democratic Congress). It is perhaps quite possible that the tenor of the report could have been the result of the political developments of the time and the ideologies that Subba Rau and the magazine stood for.

Irrespective of the context the account shows how little things have changed in the ecosystem of a political battle over these years.