Registered with the Registrar of Newspapers for India under R.N.I 53640/91

Vol XXXI No. 21, February 16-28, 2022

Lost Landmarks of Chennai

- Sriram V

A Ship Called Madras

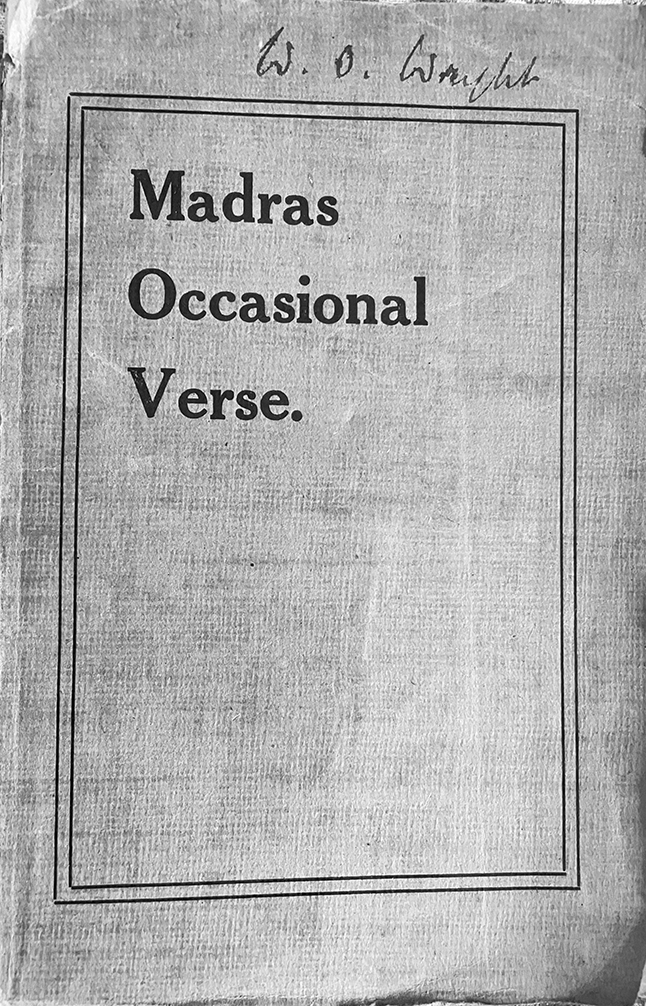

I happened to be at Higginbothams’ bookstore a month ago. While there, the manager in charge during the course of a conversation said he had recently acquired a book of poetry on Madras, published in 1915 by Higginbothams. I was intrigued. The only book of poetry on the city I knew of was Madras Madrigals and that was from the 1920s. He then had the book brought for my perusal. It was a green and gold hardcover edition, titled Madras Occasional Verse. The preface said that it was part of a fund-raising effort for the hospital ship Madras. And that brought to mind a long-pending story that I had determined to write for Madras Musings.

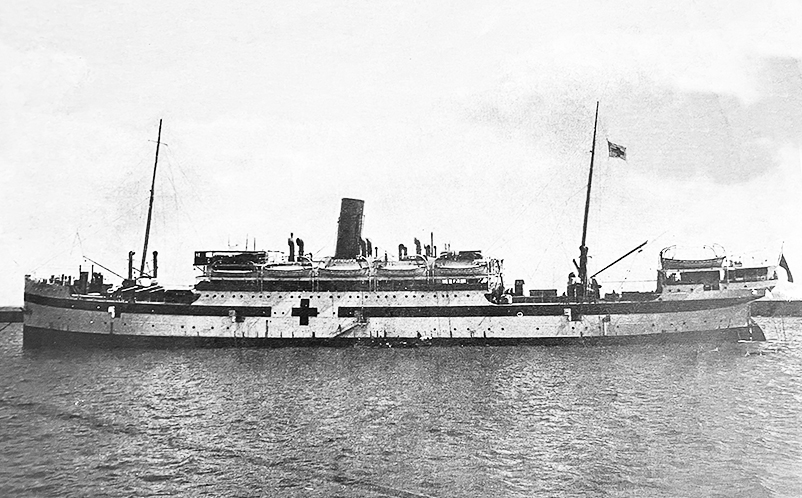

I had first come across the name of this ship in Somerset Playne’s Southern India, Its History, People, Commerce and Industrial Resources, published in 1915. A picture of the ship forms the frontispiece of the book but there is no other mention of it in that magnum opus. The internet was much kinder and gave me an article written in November 1914 by Lt. Col. (later Major General and Surgeon General) GG Giffard of the Indian Medical Service. He wrote that piece for the Indian Medical Gazette’s January 1915 issue and what is most significant, he wrote it while he was sailing the high seas on the hospital ship Madras. Giffard for the record, was one of the pillars of the Maternity Hospital at Egmore and had designed the facility’s iconic pelvis-shaped main block. It is named after him.

World War I broke out in 1914 and all the colonies became involved in raising money and resources. The Madras War Fund was created and soon collected enough for the kitting out of a hospital ship. The British India Steam Navigation Company’s SS Tanda had just returned from its maiden voyage to Japan, its hold full of coal. It had been built by Alexander Stephen & Son, Glasgow earlier the same year. The Madras War Fund decided to acquire the vessel and convert it into a floating health facility exclusively meant for Indian sepoys or soldiers. It must be remembered here that the contributions of Indians to WWI is largely forgotten, and it is only in recent years that subaltern studies have begun revealing several facts. Native sepoys in short formed the bulk of the British war effort and suffered enormous casualties in alien lands and in an inhospitable climate.

Time was short – the ship was taken over on 10th October and it had to leave Madras within a month, fully kitted out as a hospital. How this was done speaks volumes of the efficiency of the business houses that then existed and flourished in the city, many of them mere names today. Everything from the interiors to the paint on the outside had to change. It did not help that the monsoon that year was one of the city’s worst in living memory. But work did progress nevertheless.

The vessel itself was ideally suited for the purpose as it was designed for transporting Chinese emigrants and had five large decks that could be repurposed. The first task was to get the decks fitted out with 350 ‘navy pattern swinging cots’, 80 more beds at a lower level on mattresses, 20 cots for Indian officers and six cabins for European officers. The cots came from Beehive Foundry on Broadway, owned by the departmental store of Oakes & Co. While the latter was early on absorbed by Spencer’s, Beehive still survives after a fashion in Broadway/Prakasam Salai. The lower deck, where the swinging cots had to be fixed, was found to be made of steel and this posed a problem – each cot required twelve bolts to be bored into the steel. Fortunately, the Perambur workshops of the Madras and South Mahratta (M&SM) Railway had electric drills and these were pressed into service. Next came the question of the bare steel floor – always a challenge especially in cold weather which the ship was bound to sail in when around Europe. Parry & Co tackled this by supplying ‘rubberised sheets’ to cover the entire deck. But that was not all – a hospital had to have stores, an operation theatre or two, facilities for nurses, doctors and attending staff. That required extensive planning as well.

The main deck had first and second-class cabins and also the second-class dining room. The last-named was stripped of all its fittings and converted into two operation theatres, separated by a ‘white curtain of washable drill’. The cabins were removed and the space utilised for the surgeon’s preparation room, recovery ward, X-Ray room, photographic section and bacteriological laboratory. Two manually operated lifts, with men pulling them up and down using a rope and later a steam winch, were installed. The nurses had a sitting room made out of two repurposed cabins. The top deck had the cabins where the European officers stayed and the saloon deck, which initially had a music room, a smoking room and the first-class dining room, was soon transformed – the music room became the officers’ mess, the smoking room becoming the mess for students and assistant surgeons. The first-class dining room became the common facility for everyone with specific and rigid timings of use. A laundry was installed – this was a brand new facility that had just come in from England for use at the Maternity Hospital. No doubt it was Giffard who suggested that it could be handed over to the ship, provided the War Fund immediately procured one for the hospital. The steam for the ship’s disinfecting and laundry services came from boilers supplied by the Public Works Department workshops (in the Seven Wells area).

All the carpentry was executed by the M&SM Railway Workshop and the sanitary fittings came from Oakes & Co. It was only when work was nearly over that a new problem was discovered – all the equipment having been sourced from Madras ran on 225 Volts supply while the ship had only 100 V DC. Fortunately, for the ship, Siemens & Co located two generators in the city and supplied them at short notice and so as Giffard writes,

“the operating table can be warmed, the laundry machinery driven, the surgical arc kronig lamp and the X-Ray apparatus worked, the sterilisers worked, the pantostat run, the bacteriologist’s centrifuge activated and the ward vacuum cleaners made to suck, etc.”

The lowest deck had the stores, and these were stuffed with supplies from the Government Medical Depot. There was space for six wards in the ship and in addition there were servants’ godowns, an armoury, guard rooms, a prison and a strong room that had gold – this was so that emergency purchases could be made at any port of call without worrying about currency exchange. Even as the ship was being readied purchases for the stores was kept up at a steady pace – enough to last six months of voyage. All of it was kept in large warehouses provided by the Madras Port Trust.

The HS Madras was ready by early November 1914 – its outside gleamed in white and yellow – the former in the hull and the latter in the funnel and upper portions. A scarlet band ran along the side, and this had at its centre the ‘Geneva Cross’ (precursor to the Red Cross) painted in scarlet as well. This was illuminated at night so that enemy ships would know that the vessel was a medical facility. On November 17, 1914, the HS Madras, sailed out of the harbour, with just three people to see it off – Governor Lord Pentland, Lady Pentland and the Surgeon General. A white flag with the scarlet Geneva Cross fluttered from the main deck.

The HS Madras had a long and distinguished career as a hospital ship during WWI. In 1920, with the war having ended the previous year, the vessel was returned to the BISN Co and reverted to being the SS Tanda. It was sold to the Eastern and Australian Steam Ship Co in 1924 and remained in service till 1944. That year, on July 15, while it was on a journey from Melbourne to Bombay via Colombo, it was torpedoed and sunk by a U-boat off Mangalore. It had begun life just before WWI and it was fated to be destroyed during WWII. But its greatest hour was when it was a hospital ship, named after our city.

Having returned from Higginbothams, I googled Madras Occasional Verse – there was no copy on archive.org, my go to place for free downloads of antiquarian publications. But there was a physical copy available on sale at a stiffish price with a second-hand bookseller in England. I ordered it, hoping that my wife would never discover this splurge (she did but that is another story.) The book eventually arrived – it was a paperback, and a reprint dating to 1929, by Hoe & Co. The cover revealed that this copy was once owned by Sir William O Wright of Parry & Co. The verses inside were mediocre in the extreme and what is more, would be classified as downright racist today. But that is a story for another day. A small satisfaction is that all that horrible poetry was compiled for part-funding a hospital ship called Madras.