Registered with the Registrar of Newspapers for India under R.N.I 53640/91

Vol. XXXII No. 22, March 1-15, 2023

Knit into Pearls – The Knit India Through Literature series

-- by Ranjitha Ashok

A NOTE

The Shriram Group has been committed to the preservation and promotion of Fine Arts, Indian Culture, Heritage and Literature. For the last 35 years, the Group has been sponsoring and organising South Indian Classical music programmes of young, budding and senior artists. We have been extending support to the sabhas during the Music Season every December in Chennai.

Also, we have been organising Bharathiyar Vizha every year, conducting Oratorical Competitions, rewarding the prize winners and organising a major programme in which Tamil Scholars speak on Bharathiyar and his works.

One of the greatest and well-known Tamil writers of our times is Mrs. Sivasankari whose prowess and focus on social and human issues, interpersonal relationships, awareness on alcohol & drug dddiction, etc. have earned her a unique place amongst the writers.

During one of my recent conversations with her, she mentioned about her book Knit India Through Literature which she has undertaken as a ‘Tapasya’ for 16 years. It is her Magnum Opus, for which she has travelled all over India and interviewed eminent writers of 18 languages.

The author had completed the book in the year 2009. It struck me that we, in the Shriram Group, should take it up as our CSR Project and place her Book Knit India Through Literature in major Libraries, Universities, Colleges across India and in the hands of eminent Writers.

As a contribution to our country, the Shriram Group has taken up this task and I have derived personal satisfaction in being part of this great endeavour.

On 18th March, we will be organising a programme at The Music Academy in which Mrs.Sivasankari will be honoured and felicitated and the four volumes of the book Knit India Through Literature will be formally released by distinguished personalities from the field of Literature.

This will be followed by a music concert by Sangita Kalanidhi Smt. Aruna Sairam who will sing in various languages.

This will be a fitting tribute to Sivasankari for her singular contribution to Indian Literature and Heritage. Such a work cannot be attempted again. Therefore, it is, indeed, a precious gift to India. Let’s celebrate the Author and the Book.

Dr. Akhila Srinivasan

Director

Shriram Life Insurance Co. Ltd.

* * *

18 languages, nearly 100 writers, four volumes representing the four cardinal directions of the nation, 16 years of gruelling hard work, tireless commitment, and belief in a dream…

That, in a capsule, is renowned writer, Chennai’s very own Sivasankari’s magnum opus – The Knit India through Literature series. Sivasankari began working on the project in 1993.

Why 18 languages? That was the number given in the Eighth Schedule of our Constitution when she started, so Sivasankari stayed with it.

The four volumes, beginning with The South, were launched between the years 1998 and 2009.

The Seeding:

The first question that springs to mind is ‘Why’? Why would Sivasankari, given her already-achieved phenomenal success and status as a literary icon in Tamil Nadu, undertake a task of this magnitude?

Two reasons.

Back in the late 80s, after participating in a literary meet in Mysore analysing the work of an African American writer, a thought occurred to Sivasankari – while the Indian participants had knowledge of world literature, they were largely unaware of literary works in languages and States other than their own within the country. Later, at a writer’s meet in Sikkim, she found that for many participants, the South meant ‘idli-sambar and Kanjeevaram silks’. With this came the realisation that the same stereotypical thinking was common to everyone, including herself.

The thoughts led to questions that grew into the ‘Knit India’ project.

You understand the catalysts – but on this scale? And all alone?

‘As a fiction writer, I take a small speck of truth and develop it into a huge novel.’ Sivasankari says, ‘This was similar. The seed was sown inside me. ‘Language-wise’ automatically became ‘State-wise’ because that is how India is divided.’

The First Step on a Long Journey:

‘Homework’, she says – even before beginning the project.

And since this was still the pre-internet, pre-cellphone, ‘Google-less’ era, she approached literary bodies, literary magazines, prominent national newspapers like The Hindu and Times of India, the Sahitya Akademi, the Bharatiya Bhasha Parishad, and similar organisations, requesting them to provide names of the most well recognised, respected writers and poets, region-wise.

From the start, Sivasankari was very clear about content – modern day, contemporary writers. ‘This is the writing I know. I was equally clear that I would create and stay within the framework of fiction and poetry’. This disciplined thinking was essential, and is, in fact something she applies to all aspects of her life when it comes to making choices. Which helped in creating a cohesive list as she gathered names of top writers of fiction and poets from each region.

All four books in the series follow a pattern. Every ‘direction’ is divided into States with their particular languages. Each language section begins with a travelogue, followed by in-depth interviews with representative authors, followed by respective pieces of their work. At the end of each language section, is an account of its linguistically connected modern literature compiled by experts.

‘Once I identified four to six writers and poets, I contacted them, usually by registered post, which at times took 15 days to reach.’ Given inevitable delays, it sometimes took a month or more for mutual correspondence to get underway.

This was followed by laborious research into the works of each writer selected, involving library visits and long hours of making notes.

The next stage was fixing meetings, and Sivasankari had to structure the process so that she met all those belonging to one State or region within a span of 15 days, because ‘… how much could I travel up and down, especially to places far away?’. It wasn’t just distance –expenses, personal safety and finding a time when all the writers were free were all challenges.

Her field work and her experiences here would make a great book in their own right. From ferreting out obscure addresses, to battling language issues, to navigating areas known to be dangerous – even using police escorts in places – her work needed not just courage of conviction, but actual raw courage at times.

She was her own photographer, her own recordist, but regrets not having enough funds for including a videographer. ‘So many I interviewed are no more, across each State. So many intellectual giants lost’.

Then came the crucial task of transcribing all the tapes, some of which ran into several hours over a few days. Here, the South volume proved easy. There was so much publicity after the launch, that readers and friends like P.C. Ramakrishna voluntarily came forward offering their services.

And here’s where she realised how naively optimistic she had been. Always a fast worker, she had imagined that in seven years, she would be ready with four volumes. Instead, it took her six years to bring out the first volume.

After six years, when she began work on the East collection, things got tougher. Her volunteers had a problem with the differences in pronunciation, and began returning the tapes, worried about making mistakes. Sivasankari had already by then begun preparing for the next volume. Her secretary Lalitha rose to the occasion, taking charge of the transcribing. Sivasankari picked up a transcriber in Singapore, which ran the material at a slower pace, so every word could be understood. (As an aside, she adds that all the piles of transcribed material so painstakingly put together have been donated by her to the Roja Muthiah Research Library.)

‘I learnt as I worked.’, she says. ‘Through trial and error. Since no one had attempted anything like this before, there was no one I could turn to for advice. The discipline I have always used while writing helped.’

The final step was the all-important one – finding a publisher.

‘I had by then published more than 150 books, but for the very first time, I paid to have the first volume published, as no publisher came forward to publish the English version. The Tamil version was ready; I wanted to bring out both versions simultaneously. This is a Pan India project, after all’. So, Sivasankari paid for the first English version as the general opinion was that while the content was much appreciated, this was primarily research work, and even her name wouldn’t help sell it.

Throughout, Sivasankari deliberately stayed in the background, maintaining a low profile. ‘No one outside of Tamil Nadu had any inkling of who I was, what my position was as a writer in my home State’.

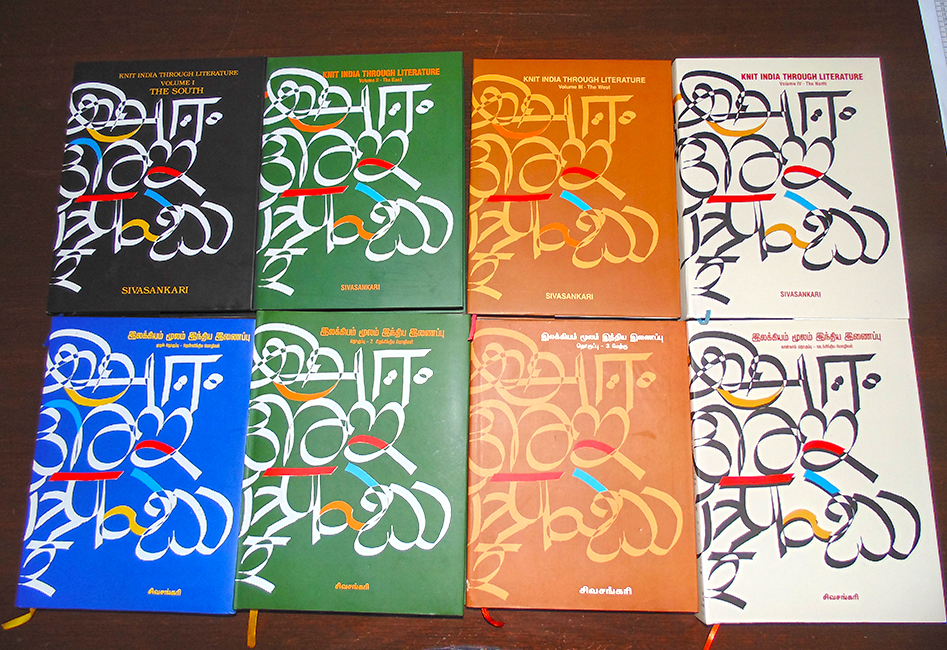

She began with The South volume first, choosing to start with Kerala, ‘…as India begins there. I wanted meaning and symbolism in every aspect.’ The very arresting wrappers for each volume by the famous art director and production designer Thota Tharani tell their own story. Apart from the variety of alphabets sprinkled across the wrappers, the colours mattered too – darkest blue for the peninsula, green for the verdant East, brown for the West with its deserts, and pure white for the Himalayas in the North.

‘For 16 years, I breathed, ate, and slept this series – and thought of nothing else. I was someone possessed. Tapas is the right word. When I look back, I wonder how I did it.’

A firm believer in Divinity, she believes that it was ‘God’s work and His Grace’, which gave her ‘…the idea, methodology, resources, contacts, and the strength to do this.’

Speaking of which, how did she find the strength to stay committed to this admittedly Herculean task for 16 whole years?

‘Two very strong reasons. First, I love my country. I am a very proud Indian. I wanted to do this for my country. My goal was never commercial success. My main objective was to introduce Indians to Indians through literature; and for younger generations to get the right perspective about this great country they live in. Secondly, it is Literature that has given me status, recognition, love, and respect. From all corners of the globe, people come to me saying I helped shape their lives through my work – it is writing that has given me this honour. I had to give something very meaningful back to the world of literature – not Tamil literature alone, but to my nation.’

In addition, this series is the first of its kind, as the Sahitya Akademi’s former Secretary, Indranath Choudhary said, when here for the launch of the first volume.

‘I wanted people to know a writer from Tamil Nadu had achieved this. A woman, at that’, she adds, with a tongue-in-cheek twinkle.

How did she go about raising funds?

She began by writing to important organisations. Once again, she assumed that everyone would be as excited by this idea as she was. But reality proved otherwise. Organisations conceded that while this was a very noble undertaking, they had no funds for such projects.

Luckily, she had stalwarts in her corner, who helped in various ways, to all of whom she is deeply grateful – Mr G K Moopanar, writer Maalan, Jayanthi Natarajan, and later, when it came to publishing, friends like Redington Srinivasan and others, and institutions like The Hindu who sponsored The South volume.

She took on everything else, saying it was akin to providing for four children. ‘Each volume is my child.’

She also expresses her gratitude to the writing community in India at large, who proved very supportive. Amazing, when you consider that here was a writer from Tamil Nadu who wrote primarily in Tamil, so many didn’t even know who she was, had no connect with her at all, but they were willing to give her any help she needed, respected her work, and were thrilled with her project. Some writers like Nirmal Verma battled extreme ill health just to talk to Sivasankari.

The interviews are a priceless collection on many levels, especially as some of them were the very last ones certain writers gave before they died. The forewords are interesting, written by writers not from the regions being showcased in that particular volume. So, Vol 1, The South, has a Foreword by Khushwant Singh; In Vol 2. The East, by M T Vasudevan Nair; Vol 3, The West, it is Manoj Das, and for Vol 4, The North, it is Damodar Mauzo.

Her precise questions to each author reflect such a depth of study of that particular writer’s oeuvre and general work, you have to wonder about the hours of research and reading up she must have done, of not just the backgrounds of the author but of the history of that particular body of literature.

‘I studied.’ comes the deceptively simple answer, ‘To ask questions, I had to prepare.’ Discipline played a part here too, as she ‘reined’ herself in, focusing strictly on the information needed from and about any given writer being interviewed.

And there was a most rewarding payoff. Writers greeted her questions with pleasure, often sitting up in amazement, exclaiming, ‘How did you know this? That hasn’t even been translated into English’ Padma Bhushan K.S. Duggal, writer and Rajya Sabha member, exclaimed: ‘Warre Wah! Your question reveals the extent of your homework before undertaking this interview!’

Sivasankari played no role in choosing the specific stories and poems representing the work of every writer featured in the series. ‘In each case, I requested the author or poet concerned to give the piece they wanted included in this collection, the translations, in which she ‘…merely corrected the grammar – nothing else’.

Each writer’s voice had to come through.

Every section ends with a piece tracing the path of modernist literature of that particular language, taken from the anthologies of Sahitya Akademi with their permission. Sivasankari calls this the ‘Scholars’ section’, adding that it was important for her to include this as ‘…this adds seriousness and weightage to the book, offering a cross-section of the language in its entire sweep, an analysis of the track it was taking.’

Was there any backlash from those who felt left out?

Not really, she says, nothing she can point out.

Wouldn’t the introductory travelogues, so absorbing and informative in themselves, make a great book? ‘It’s been done – in Tamil, and is called ‘Bharatha Darisanam.’, comes the reply.

The Interviews

By the time you reach the fourth volume, you realise this has been a learning process for you, and you are now painfully aware of how little you know about writers within your own country – a humbling thought. Their voices, their words, speaking of shared thinking and experiences, stay with you.

Of how they reject discrimination of any kind – those based on gender, with women refusing to be labelled ‘a woman writer’, and those that differentiate between the ‘literary’ and the ‘popular’, between so-called ‘art’ and ‘commercial’ literature – good writing is all that matters and can appear anywhere. And Sivasankari believes this is a decision best left to the readers. And to Time. ‘50 years from now, if people still feel the impact of a piece of work – that is literature. That is a classic.’

Of poverty-ridden childhoods in unstable environments, which would be true for nearly 50 percent of those interviewed, Sivasankari says. You think of Laxman Gaikwad, who called himself a ‘moolnivasi’ a true son of the soil, who was beaten by his father for writing in his school notebooks, thus destroying ‘the beauty of the pristine white pages’…that was the level of naïve ignorance his forest-dwelling family, part of a de-notified tribe, displayed. Gaikwad went on to win the Sahitya Akademi award for his novel ‘Uchalya’.

Of how, while there are forces that ‘control and manage literary markets,’ regional writers have their ‘trusted readership’.

So, is there an English-Regional divide in the minds of publishers?

‘Definitely’, Sivasankari says. ‘I might be a most sought out writer in my regional language, but when it comes to English translations of my work, English language publishers are reluctant to publish.’

Of how a tragic thread of shared abandonment runs between the Sindhis, the Urdu-speaking people, Kashmiris, and Punjabis – their work reflecting the pain of their history, of Partition, of being rendered homeless overnight. The South has not experienced that. (You agree – those interviews are particularly gut-wrenching.)

The pages are sprinkled with stars – the best writers in the land, Sahitya Akademi and Jnanpith awardees – and it is awe-inspiring to witness their pure love, that almost worshipful devotion to language, to the written word. For them, every word has ‘a body, a soul, a vibrant rhythm’ and life of its own, carrying different shades of meaning. Simple communication lies at the very heart of good literature, while overthinking is deterrent to spontaneous writing.

For the writers the word – authentic, truthful and from the heart – is powerful beyond imagination, especially when imbued with empathy, and can change the way of thinking of an entire people.

Is The Word that powerful?

Yes, says Sivasankari, judging by her own experiences over the years. ‘People tell me my work changed their lives. ‘I read Oru Manithanin Kathai and gave up alcohol,’ some say. Malayin Adutha Pakkam inspired women who had lost their husbands to reclaim their lives for themselves.

And never underestimate your readers, says Sivasankari. ‘Leave spaces in between your work, so they can decide for themselves. I don’t preach; I stay non-judgemental. I only share my ideas, experiences. And I share because I care’.

Is there a sense that some languages have it a bit harder than others?

‘Definitely. Languages like Konkani, Urdu, Indian Nepali and Sindhi. It’s simple – people without a State feel this the most. There is no one to fight for you. No Government support.’ Konkani, she points out, is stronger these days.

An ability to think and be comfortable in different languages is a uniquely Indian trait, and that is the kaleidoscope that is India. As Dr. S. Radhakrishnan said, all Indian literature is one, written in many languages.

‘Language, which is such a gift, can also divide us. Being separated by language is sad. We hardly know each other. I wanted to introduce my fellow Indians to their own vast literature. This is my homage to Language as an entity.’

And finally…

Sivasankari had four launches – The South in Chennai, at the Connemara; The East in Kolkata, organised by the Bharathiya Basha Parishad; The West in Goa; The North in Delhi.

What was her primary emotion after the fourth volume was launched?

‘Sheer exhaustion. But in a nice way. I had not written a word of my own writing during those 16 years of hard work. And I did not touch my pen for the next ten years. Except for a couple of travelogues. It is only four years ago, during the pandemic, that I took up my pen again, and wrote ten short stories. I also wrote my autobiography, Suryavamsam. Now, I happily do nothing.’

Sivasankari has taken a deliberate decision to withdraw over the last 10 years, on the lines of the ancient concept of vanaprastha, moving steadily towards sanyasa. Not so much a physical but a mental state.

While there is no bitterness, there is perhaps some sadness. Nearly 100 intellectuals have been presented – this work should have been done by organisations that represent the literary landscape of the nation, she feels. People still don’t know enough about this mammoth research project nearly 14 years on. ‘It is thanks to efforts of my friends both in India and abroad, and to people like Akhila Srinivasan of the Shriram Group, that awareness is now being created.’

You agree – this series needs to reach the nation it was meant for, to help create an appreciation of serious literature, and of the writing that has come out of all regions and languages. (And, you can’t help thinking, the nation needs to acknowledge this author.)

Manoj Das compared Sivasankari’s journey to that of the ancient Gunadhya, who, travelling in the four directions like she did, collected what became the Brihatkatha, much of which was lost. What remained was later compiled and translated into the famous Kathasaritsagara by the Kashmiri scholar Somadeva.

Imbued with the same compelling creative urge, she is the ‘spiritual heir to Gunadhya.’

sweeping through India in the garb of a literary activist, turning her very journey into a story.

This entire project is a symbol of Sivasankari’s commitment, hard work, her deep love for her country, and her passion for language.

Little wonder then that that most enigmatic Lady-in-White has always smiled upon her very illustrious daughter.

The four-volume set of Knit India Through Literature is being offered at the discounted rate of Rs 2500/-. For further details, please contact Mr. Ramanathan at Vanathi Pathippakam, (Publishers), No 23, Deenadayalu Street, T. Nagar, Chennai 17.

Comments