Registered with the Registrar of Newspapers for India under R.N.I 53640/91

Vol. XXXIII No. 1, April 16-30, 2023

Beyond Cricket – A Life in Many Worlds

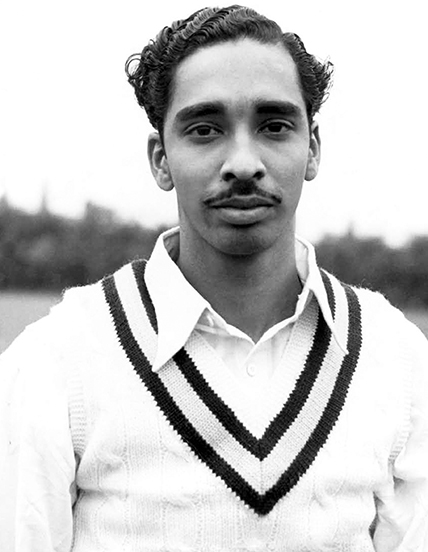

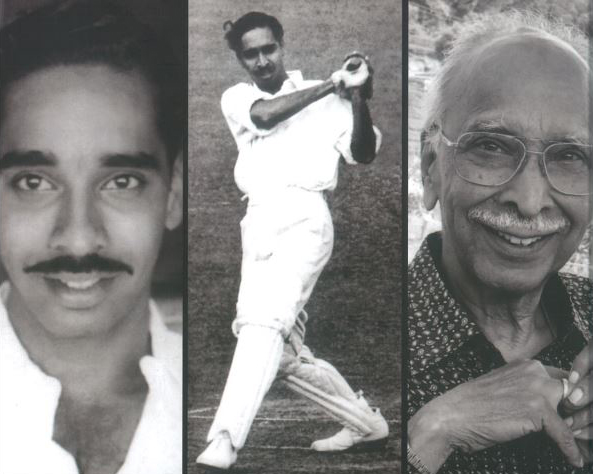

CD Gopinath, at 93 is the last surviving member of India’s first test cricket team. This ace sportsperson, who has also had an actioned-filled corporate career recently had his memoirs penned with the help of ace cricketer and Madras Musings stalwart V. Ramnarayan.

Beyond Cricket, A Life in Many Worlds, by C.D. Gopinath with V. Ramnarayan. Published by Wordcraft, Chennai 600018. For private circulation only. We present excerpts from the book.

* * *

An Aristocrat Among Cricketers

In his nineties now, he is the lone survivor from India’s famous first Test victory. On 10 February 1952, he caught the English fast bowler Brian Statham off the left arm spin bowling of Mulvantrai ‘Vinoo’ Mankad on the long on boundary, thus wrapping up a massive innings win over a D.B. Carr-led England team at Chepauk. His memory is crystal clear, his articulation measured, stylish and accurate to the extent that he can recall most of his cricket experiences from the 1940s, all this in a manner that can shame today’s AI-driven data analysts and statisticians. For a man regarded by fellow cricketers, administrators and cricket writers as one of the more gifted and elegant batsmen of the 1950s and a shrewd captain with keen tactical nous rarely seen at the domestic level during the 1950s, Chingleput Doraikannu Gopinath had an all too brief run as a Test player. This, despite a most impressive debut in the Bombay Test against the touring Englishmen in the 1951-52 season, and his useful contribution to India’s first triumph.

Gopinath was the aristocrat of the Madras team of the 1950s. Not only was he from an elite social background — his father C.P. Doraikannu was Chief Accounting Officer of Imperial Bank of India, Madras State and General Manager of Indian Overseas Bank – his cricket too was regal. He batted with panache, and seemed to have the kind of time to play his shots that tends to invest batting with an air of majesty. Of erect stance and equipped with a range of shots all around the wicket, he averaged over 50 in Ranji Trophy cricket during an era of uncovered turf wickets and matting.

His parents, C.P. Doraikannu and Hamsammal.

His parents, C.P. Doraikannu and Hamsammal.He scored two brilliant hundreds in the year Madras won the national championship for the first time under Balu Alaganan’s stewardship, sharing the batting honours with his younger teammate A.G. Kripal Singh. He made 122 against Bengal in the semi-final and 133 against Holkar in the final. As he had earlier been away on India’s first cricket tour of Pakistan, those were the only two Ranji matches he played that season, and they also happened to be his first two hundreds in the championship.

He had debuted in the Ranji Trophy in the 1949-50 season, starting inauspiciously with a pair against Mysore. His 74 and unbeaten 53 against Mysore at Bangalore in the next season should have cemented his place in the state team, but he only truly consolidated his position in the side through his contributions as batsman and part-time captain during Madras’s maiden Ranji Trophy triumph.

In a conversation with me, the late Alaganan – who lauded Gopinath’s role in that success, along with the parts played by Kripal Singh, the star of the season, M.K. Murugesh, A.K. Sarangapani and others – had also credited Gopinath with vital tactical inputs. Among other things, he said, “In the semi-final, CD Gopinath plotted Pankaj Roy’s dismissal on the hook shot off the bowling of BC Alva with his fastish offbreaks. We had a fielder about halfway to the boundary, Alva bowled short and Roy could not resist the temptation.”

C.D. Gopinath leading the team on to the field at the South Zone finals Tamil Nadu vs Mysore, Bangalore February 4, 1956.

C.D. Gopinath leading the team on to the field at the South Zone finals Tamil Nadu vs Mysore, Bangalore February 4, 1956.Gopinath, who became State captain the season following Alaganan’s retirement, came to be known for his shrewd captaincy and exceptional people skills, but could not repeat Alaganan’s Trophy success, though he continued in his role till 1963. He had been a major success as captain of the Madras Cricket Club in the local league, leading the team to the Palayampatti Shield title in his very first season as captain in 1957-58. He was 27 then. He repeated the feat the following season, and twice again in 1960-61 and 1965-66. As captain of Madras, Gopinath relied on his spinners led by the champion leg spinner Kumar, and played a key role in the development of his bowlers. By his own admission, Kumar just followed the captain’s orders in his early years – to great advantage.

As a batsman, Gopinath had an impressive record of nine first class hundreds including a highest of 234 against Mysore in the Ranji Trophy and a grand 175 versus the touring New Zealand team in 1955.

After studying Gopinath’s career record of intermittent opportunities, and having watched him bat with great style and confidence, I find it difficult to resist the conclusion that he did not receive a fair deal from the selectors. His was certainly a talent worth nurturing. In domestic cricket, he continued to bring joy to the Madras partisan, with several top innings of great authority.

* * *

My Early Days – by C.D. Gopinath

I was born in the summer of 1930 when the whole world was reeling under the pressure of one of the worst economic depressions in history. The day I was born at Madras was traumatic for the local populace. During a procession of people protesting against the government, an overenthusiastic British policeman opened fire and shot two locals to death, causing a riot. The government then imposed a curfew whereby no one was allowed to be outdoors after six p.m. A “shoot to kill” order went out against those violating the curfew.

I happened to come into this world on that day and the doctor who came to attend at the childbirth prescribed a medicine to be administered to the newborn as soon as possible. In those days, medicines had to be made according to the doctor’s prescription by a “compounder”, and my uncle was asked to go out and get this done. He had to sneak out through bylanes and side streets to the compounder’s home and persuade him to go to the medical store to get it done. Luckily nothing untoward happened and he was able to find his way back home with the required medicine. My mother told me that the name of the newborn in the prescription written by the doctor was “Baby Gun”. She was convinced that it was this incident that made me keenly involved with guns and shooting in later life.

My childhood, except for a brief interregnum, was the happiest a boy could hope for, both at school and during some carefree time I spent out of school, with my father, in Andhra. My siblings, all older to me, were staying at Madras under the watchful eye of my grandmother who set up home there to take care of their schooling. My mother Hamsa and my father CP Doraikannu were perfect role models at whose knees we learnt all the important lessons—of honesty, kindness to those less fortunate, and love of nature. My father, an officer of the Imperial Bank of India – a Scottish establishment eventually to be nationalised as the State Bank of India in 1955 – was in the 1930s posted at Cuddapah, Andhra, then still part of the Madras presidency. When I was around six, I joined him and my mother there, and life then became a delightful adventure. Father who had many accounts and clients under his control, often travelled all over the province to inspect agricultural farms and other client units by road in his car, and he took me with him everywhere. It was during these outings that I became closely acquainted with the flora and fauna of the south Indian countryside, camping in the jungle, and enjoying the glorious diversity of the landscape. My love of nature was therefore off to a most effortless start, with a firm foundation that stood me in excellent stead in my adult years.

Such an idyll was too good to last, and I had to join my siblings at my grandmother’s place at T’Nagar, Madras, and start school there. I was admitted to the Holy Angels Convent School on Theagaraya Road, a girls’ school which took in boys up to the middle school level — after which the boys had to look elsewhere for their further schooling. I was eight when I joined Holy Angels — which, by the way, still operates out of the same precincts. Unfortunately, I had sufficient cause to be unhappy there, thanks mainly to the impressive wristwork of one of my teachers, who swung a quite deadly ruler aimed at my knuckles whenever she found me falling short of her expectations in English Dictation Class. The trouble was that I was probably slightly slower than she expected, reaching the fourth sentence of the dictation by which time she would have reached the 24th! I could not bear the awful daily pounding my knuckles were taking, and decided to take control of the situation after a few days of this kind of third degree treatment. With a child’s native ingenuity, I started reporting sick during English Dictation, and spending quality time in the sick room. I soon realised however that this was no permanent solution to my problem.

What I then proceeded to do was nothing short of inspirational. Ostensibly setting out to expand my mental horizons with the help of modern education, I took to making a slight detour from school every morning, ending up instead inside Panagal Park, a famous landmark of the neighbourhood. There, I spent the day, enjoying the fresh air and cool breeze and cavorting around, timing my return home to coincide with the closing bell at school. Soon I grew tired of entertaining myself, and in an early indication of my leadership skills, managed to recruit a partner in crime, a classmate grateful for this unexpected treat from heaven. Our delightful act of truancy must have continued for about a week, when an elderly relative unwittingly chose to spoil our party. Taking a shortcut en route to my grandmother’s house, he was no doubt delighted to have the unexpected pleasure of running into me, but also intrigued to find me in the park when I should have been warming my school bench. He learnt to his surprise from two overly earnest young children that he had interrupted our enjoyment of a holiday. To our relief, he went away, apparently satisfied with this perfectly legitimate explanation of our presence in the park, but the next thing we knew, we were joined in the park by Grandma. That was in effect the thing we knew, end of my freedom from English Dictation.