Registered with the Registrar of Newspapers for India under R.N.I 53640/91

Vol. XXVI No. 10, September 1-16, 2016

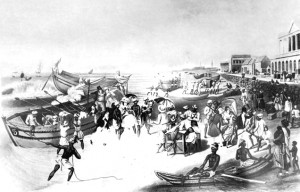

Riding the surf of Madras

‘Masoola boats’.

‘Masoola boats’.

Excerpted from Madras, Mysore and the South of India: A personal narrative of ‘A Mission to those Countries’ by Elijah Hoole, published in London by Longman, Brown in 1829.

Madras, like the rest of the Coast of Coromandel, possesses no harbour. The communication between the shipping and the shore is carried on exclusively by Masoola boats and catamarans. The form of the boats is exhibited in the accompanying sketch, taken from the beach at Madras: they are here represented, as they usually appear when waiting for employment, lying high and dry on the sand; that on the left shows the manner in which they are pushed off; the men who are employed in launching, climb into the boat, with astonishing ease, as soon as it is afloat. These boats, which are from twenty to thirty feet in length, and about six feet in depth and breadth, are constructed of strong planks, bent by means of fire; stitched together, through holes drilled all round the edges, with thread or cord of coir, the outer fibrous covering of the coconut; inside the boat, the stitches enclose a sort of calking or wadding of straw, rendering the seams water-tight. Masoola boats are generally manned by ten hands, eight men at the oars, one at the helm, and a boy to bale out the water: they strike their oars with great regularity, keeping time by a song kept up by one voice, the whole company joining in chorus at the end of each stanza.

There are usually three waves to be passed between smooth water and the shore ; these waves frequently rise to the height of six feet and upwards, and, breaking with a curl, the highest part of the wave falls over first, leaving a kind of hollow underneath. Unless well managed, even a Masoola boat would be overwhelmed: any other kind of boat would perish.

Landing in Madras in the early days.

Landing in Madras in the early days.

The boatmen, accustomed to the surf, are very skilful in avoiding its violence: when they come towards the first wave, they rest on their oars in total silence, and the helmsman directs the boat into the most favourable position; when it begins to rise on the wave, they at once burst out singing, Ale, Ale, “A wave, a wave,” and pull away with all their might, till the wave has expended itself ; while the passenger does well to cover himself from the spray with his boat cloak. They then rest, waiting for the succeeding wave, which is passed in the same manner, till the boat is thrown almost dry upon the beach, and the men jump out to secure it from being carried back.

In passing the surf, I have often noticed that the wave, before it is expended, strikes the boat so severely, as to excite some apprehension ; and there have been instances of the boat having been dashed to pieces by its force, with the consequent loss of the lading, and endangering of the lives of the persons on board. The boats employed in embarking or disembarking passengers are therefore often attended by catamarans.

A catamaran (in Tamul kattamaram, from kattal, “ to tie or bind,” and maram, wood,” literally tied wood, or timber lashed together) is a raft, from twelve to fifteen feet long, by three to five feet in breadth, composed of three spars or logs of light wood, lashed together; and managed by two or three kareiars, or beachmen, persons of the same caste as those employed in the Masoola boats.*

When the surf is so high that Masoola boats cannot venture, catamarans are used to communicate with the shipping, usually anchored two to four miles from the shore: the men secure letters, or small parcels, in their conical caps, formed of the leaf of the palmyra-tree: larger packages, covered with canvass or wax-cloth, are lashed to the raft; and they fearlessly venture into the most tempestuous seas. Though sometimes washed from the raft, their dexterity in swimming and diving enables them to regain it ; and the loss of a man, in this perilous occupation, is of rare occurrence.

Besides these important services, the catamarans are generally used in conveying the mails, in stormy weather, from the coast of Coromandel to Ceylon, a passage of sixty miles. They are also used by the fishermen, all down the coast. On fishing excursions, they generally go in a party, setting out early in the morning, well supplied with nets and baskets. When outside the surf, they carry a neat three-cornered sail, and proceeding many miles to sea, do not usually return till evening.

I remember to have seen the Captain of a vessel, driven by a heavy storm from her anchorage off Negapatam, while he was ashore, set out in quest of her, seated on a chair lashed on one of these catamarans. He thus crossed the straits, which divide Ceylon from the Continent, and succeeded in finding his ship.

* The kareiars, or persons thus employed on the beach at Madras, amount to many hundreds, residing chiefly at Royapooram, a village to the north of the town : they are generally Roman Catholics. A Masoola boat can make three or four trips to merchant vessels in the course of one day. The regulated charge for each trip is fifteen fanams, or near two shillings and four-pence sterling. Vessels of war anchor at a greater distance from the shore; consequently, a trip to them is charged double the amount, and two trips only are made in the day. When in full employ, therefore, these men do not gain more than one shilling each per day. Small as this sum appears, they have of late years contributed out of it to liberally, as to raise for themselves a large and substantial church, in Royapooram, the erection of which cost several thousand pounds.

Thanks to R. Bhaskarendra Rao for sending these excerpts.