Registered with the Registrar of Newspapers for India under R.N.I 53640/91

Vol. XXVI No. 12, October 1-15, 2016

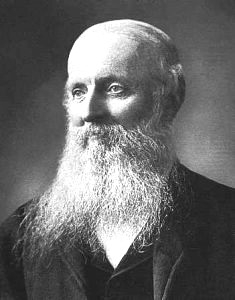

The man who saved our forests

(By Dr. Anantanarayanan Raman)

Henry Noltie, no stranger to Indian botanists, is an admired botanist and enthusiastic plant and botanical-art historian of colonial India and of the Madras Presidency in particular. He wrote two magnificent volumes on Robert Wight, another Scot, who revolutionised the understanding and management of economic plants of the Indian subcontinent. His latest works* are on Hugh Cleghorn, Indian Forester, Scottish Laird.

Hugh Francis Clarke Cleghorn was born in Madras on August 9, 1820. In 1824, the Cleghorns returned to Scotland, where Hugh Cleghorn qualified for an M.D. from the University of Edinburgh in 1841. During his university years, he became interested in plants. He returned to Madras as a member of the Indian Medical Service. He first served in the Madras General Hospital, and later in Mysore (Shimoga). While at Shimoga, economically important plants fascinated him.

In 1848-1851, he went back to Britain on sick leave. His association with John Forbes Royle – especially when Royle was busy cataloguing natural materials for the Great Exhibition in London in 1851 – made Cleghorn more interested in plants.

While in Britain, Cleghorn lectured at different forums on the reasons for the failure of Indian agriculture.He attributed tree loss in natural forests as the key reason. These observations stimulated the Government of India to think of introducing forest management and conservation practices to improve agriculture. The Government of Madras requested Cleghorn to organise a new Forest Department in Madras in 1855. He was appointed the Conservator of Forests of Madras in 1856.

Hugh Cleghorn

Hugh Cleghorn

Cleghorn considered railways, which were being developed in India then, a major threat to forests. His foresight in calculating that a mile (1.6 km) of train tract would utilise about 1800 wooden sleepers, becoming a threat to forests given that each sleeper would weigh between 75 and 100 kg, is admirable. He was equally concerned with the quantity of wood that would be burnt to run steam locomotives.

In 1861, he was appointed the Joint Commissioner of Forest Conservancy of India, along with another distinguished forester, one with German roots, Dietrich Brandis. He was later requested to plan forest management in the Punjab. During his secondment to the Government of India from Madras, he explored the natural forests of the Northwestern Himalaya and its neighbourhood. The forest conservancy methods he had launched in Madras Presidency during his leadership were of high value and relevance in all-India forest management.

He officiated as the Inspector-General of Forests of India for a while, when Brandis was on leave. On retirement in 1869, Cleghorn returned to Scotland and lived in Strathivie until his death in 1895. Cleghorn (Apocynaceae) and Capparis Cleghorn (Capparaceae) celebrate the life and work of Cleghorn of Madras.

Cleghorn believed in preserving natural forests, since he was convinced that they encouraged better hydraulics and therefore better landscapes. He was conscious how private timber enterprises in Burma indiscriminately destroyed forests and the consequences of such destruction impacted negatively on the hydraulics and landscape of Burma. Brandis writes:

‘He (sic. Cleghorn) justly laid great stress upon the necessity of acquiring a good knowledge of the principal trees and shrubs, as well as of the climate, soil, and forest growth in the different forest tracts; and in regard to the protection of the forests, he studied the chief sources of injury, indiscriminate cutting, fires, and Kumri cultivation.’

Kum(a)ri cultivation was the shifting cultivation practised on the slopes of Western Ghats of Peninsular India, about which Cleghorn has written in his Forests and Gardens of South India.

Noltie presents the Cleghorn story in two volumes: the first on the life and work of Cleghorn in colonial Madras and elsewhere in India; the second refers to his botanical acumen and the details of plants he recorded as exquisite artworks, while serving in India.

Noltie’s principal volume is the Indian Forester, Scottish Laird and it speaks of his life in India and Britain as a scientist, polymath and administrator. It also discusses the legacy he has left behind. The companion volume The Cleghorn Collection: South Indian Botanical Drawings 1845-1860 features artworks of plant materials enabled by Cleghorn over the period indicated in the volume’s title. It includes a chapter on ‘Alexander Hunter and the Madras School of Art’. Because Noltie speaks elaborately on the subtleties and nuances of botanical artworks created by various Indian artists who worked for Cleghorn, the introductory chapter on Indian artists is relevant.

In the chapter ‘Madras Polymath’, Noltie speaks of the multidimensional personality of Cleghorn. Cleghorn was associated with the Madras Medical College (MMC). Cleghorn was the professor of botany and taught Materia Medica, necessiated learning about various medicinal plants. He, therefore, used accurately depicted illustrations of plants as a teaching tool. Noltie indicates that this tactic of using accurately drawn illustrations was a capability Cleghorn acquired from John Hutton Balfour of the Royal Botanic Garden of Edinburgh.

At Cleghorn’s initiative, a museum of vegetable productions and a botanic garden appear to have been established in MMC. Woefully, no trace of these exists today. Cleghorn also concurrently played a key role in the management of the Madras Horticultural Society Garden (MHSG) (later, the Madras Agri-Horticultural Society Garden), which was established by Robert Wight in 1835.

As its Secretary, he enumerated the plants occurring within the MHSG and (over)enthusiastically titled this work Hortus Madraspatensis, getting it published through the Society in 1853. At the Madras Exhibition of Raw Products, Arts, and Manufacturers of Southern India (1855), held during the governorship of George Harris, Cleghorn, further to playing a key role in the arrangement and management of the Exhibition, displayed 28 gums and resins obtained from the trees in the MHSG, 43 wood specimens he had collected while he was at Shimoga, and a range of botanical drawings.

The chapter on ‘Gardens of South India’ speaks of Cleghorn’s role in the development of the Government Garden at Ootacamund (Ooty) (then managed by William McIvor, and which bears significant relationships with the introduction of Cinchona into India), the Lal Bagh at Bangalore, a few private gardens both in Ooty and Madras, and the People’s Park, Madras.

The bulk of the companion volume includes reproductions of carefully chosen, representative illustrations from the Cleghorn plant collections (I imagine that these are archived at the RBGE) made during his stay in Shimoga, Madras environs, and elsewhere in India. Noltie presents details including, for example, a crisp commentary on Tectona grandis and population as noted by Francis Buchanan (known as Francis Buchanan-Hamilton in later days) during his survey of the Mysore region in 1800–1801. With the fall of the Mysore Tiger, Buchanan was requested to survey southern India in 1799; his survey resulted in A Journey from Madras through the Countries of Mysore, Canara and Malabar. Cleghorn visiting the site previously visited by Buchanan, 45 years later, recognised the declined numbers of T. grandis, which he attributed to the shifting cultivation (kum(a)ri) practised in the area. This observation made in 1845 got Cleghorn to intensify his interest in forest conservation and write a seminal report on the effects of deforestation for the British Association for the Advancement of Science.

The ‘Madras Nature Prints’ chapter is illuminative. I have not known of the Madras Nature Prints. Noltie explains that these prints are direct images made from plants, especially leaves, as a way of capturing intricate patterns, such as leaf venation. In practice, this effort did away with the reliance on an artist. Noltie indicates that Cleghorn accumulated close to 300 of such monochrome colour Madras Nature Prints, most of which are archived under the Cleghorn collections in Edinburgh.

Reading the chapter that refers to the Madras School of Arts started by another Scottish medical doctor in Madras, Alexander Hunter (Hunter’s Road in Vepery commemorates Hunter), as a private art school in Popham’s Broadway in 1850, kindled pleasant thoughts in me. Today, the school functions as the Government College of Fine Arts in a different, but at a not-far-away location, in Madras. Cleghorn in 1851 found students trained at the school useful to him in creating artworks of plants and items of medical relevance (e.g., human anatomy). Cleghorn especially used the services of one P. Mooroogasen Moodaliar, a graduate of the School and later a teacher in it, who created artworks for Cleghorn. There is also mention of some of the artworks that were created at the School, especially those relating to plants.

Noltie has done yeoman service recapturing the science history of Madras and India, as he chronicled the life and science of Cleghorn, who played a vital role in recognising the scientific merit and aesthetic and economic values of Indian forests. Although Brandis too played an equally vital role, Cleghorn’s role in enabling forestry to evolve as a science in India, while spending most of active career life in southern India, is worthy of recognition. Cleghorn, assuming charge as the Conservator of Forests of Madras toured various locations of the Eastern Ghats, and thus scoped knowledge on timber trees and forests. Cleghorn’s role as a forester cannot be gainsaid in the context of Indian forestry and forest management.

As an amateur chronicler of Madras science, I learnt many details that were new to me. Let professional historians lock horns and debate whether Cleghorn’s (for that matter other botanists and zoologists of those days, as well) works had foreshadowed modern concepts – such as climate change and the effects of such changes – on present-day human endeavours. But, to me, as a simple-minded student of science, reading Cleghorn’s life and work, written in breezy prose and embellished with impressive illustrations, was enlightening. The volumes made me experience the charm of plants and at the same time feel their vibration in terms of their relevance to humans.

My hope and desire are that every Indian student of biology will read this book and know how biology and its applied disciplines have evolved over time in the Indian subcontinent. Students of history, interested in science history, too will find these volumes highly relevant.

Indian Forester, Scottish Laird: The Botanical Lives of Hugh Cleghorn of Stravithie by Henry J. Noltie.

The Cleghorn Collection: South Indian Botanical Drawings 1845 to 1860 by Henry J. Noltie. The Royal Botanic Garden, Edinburgh, Scotland. 2016. Both combined volume price: £ 30. Orders: pps@rbge.org.uk.