Registered with the Registrar of Newspapers for India under R.N.I 53640/91

Vol. XXVI No. 20, February 1-15, 2017

The South Indian and typing

The Stenographers’ Guild is located in T. Nagar, one of the busiest parts of Chennai, just a stone’s throw from a major bus depot and Mambalam Railway Station, from which shoppers continually spill out, heading for the huge jewellery and sari shops nearby. Yet down the dead-end lane on which the Guild is located there is a sense of stasis and even decay, though that may come from the rubbish dump that the municipal corporation has allowed to come up on the opposite side. But this picture-and smell-may be deceptive. According to Dr. S. Sekar, honorary principal of the Guild, which was founded to promote clerical skills, their courses are still in demand (he is also waging a furious battle with the municipality to move the dump). Between 500-600 students still come down the lane, named Guild Street, every month to learn typing on a bunch of battered Facit and Godrej machines. “Now that you can’t buy new typewriters any more, there are mechanics who specialise in keeping these going; says Dr. Sekar. “They buy old machines at auctions to make sure they have parts.” Dr. Sekar says that some students come for a specific reason: “Every six months the government conducts an exam on typewriters. You have to learn how to type perfectly, because a mistake cannot be erased and changed.” Some come to improve their English since the practice of typing from English texts may help language skills (the Guild also teaches Tamil typewriting). But while Dr. Sekar admits that nearly all must anticipate using computers, not typewriters, he says that training on manual machines is still useful: “You truly learn how to position and use all your fingers better.”

Kids in south India have routinely been sent to learn typing using some variation of this argument. “In the summer holidays after our Board exams, the first thing that was done was to send us to typing school,” says one family friend who grew up in Kumbakonam. Dejappa Shetty, who until he retired, was an executive assistant to the editor of the Mumbai-based newspaper I work for – essentially the person who keeps the office functioning – told me how he was sent to Mallyanager Typing School in Kinnigoli, a town near Mangalore which attracted students from all the smaller towns around.

The Stenographers’ Guild, T’ Nagar.

The Stenographers’ Guild, T’ Nagar.

Colleges were too few and faraway at that time, Shetty tells me, and also beyond the budget of some. “Many students like me used to opt for learning typewriting and shorthand to get jobs quicker,” he says. “Those days stenographers were in great demand in government offices in metros.” The two skills went together – steno-typists, as they were called, took dictation in shorthand and converted it directly into typewritten copy. It was a skill whose value was noted by C. Rajagopalachari (Rajaji), the south Indian nationalist leader, who was enthusiastically supportive when the idea of starting the Steno-grapher’s Guild to teach shorthand and typing, came up around 1936.

According to Chennai historian, S. Muthiah – himself a great typewriting loyalist, using an Olivetti, only his third machine since he became faithful to the brand in 1954 – the initiative came from N. Subramania Iyer, who had pioneered the development of Tamil shorthand and was then working with the Corporation of Madras, and S. Sivaramakrishna Iyer and P. Ramanuja Iyer, both “shorthand writers” with the Madras High Court. Journalists also supported the idea, with K. Ramachandra Iyer of The Mail, and S. Srinivasan and N. Rangarao of The Hindu serving on the first executive committee of the Stenographers’ Guild, which was launched on 26 September 1937, with Rajaji presiding over the opening meeting.

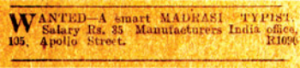

An ad in a Bombay newspaper

An ad in a Bombay newspaper

Rajaji did not just advocate the learning of typewriting for the public but made sure his family followed this too. A young man named A. Subiah had joined him as an all-round personal assistant, which included doing his typing. Rajaji’s son C.R. Narasimhan recalled how one fine morning in Salem in 1922, Subiah called and told him he had to learn touch typing. “I, who was 13 then, with no school education worth the name, accepted the ‘challenge’ and became a passably good typist within a short time.” he wrote in his book Rajagopala-chari: A Biography (1993).

Narasimhan’s typing skills were to lead to a thrilling, if occasionally unnerving, experience. In 1927, Mahatma Gandhi used his services as steno-typist, a job that he discovered was quite hard because Gandhi, due to loss of teeth, was unclear in his dictation. Narasimhan, afraid of asking him to clarify, left blank spaces in the letters, but Gandhi would sign without filling them in. When Narasimhan pointed this out, Gandhi told him he had a problem when the typists substituted their own words, but “omission is harmless’’. Gandhi was to have many typists, starting with Sonia Schlesin in South Africa; while some were from places like Bengal (Krishnadas) or Sindh (N.R. Malkani), the majority were from south India with names like Nair, Parasram, Raghava-chari, Ramanathan, Shastri and of course, Rajaji’s Subiah as well.

Once Subiah left to serve Gandhi, Narasimhan took over his role with Rajaji, in particular after Rajaji became head of the provincial government in Madras (1937-39) in one of the first experiences the Congress Party would have in actual governance. Late into the night, Rajaji would dictate ground-breaking ordinances on subjects like opening temple entry. “I would come out with the typed matter in the night itself,” wrote Narasimhan proudly. “It was also equally thrilling. It is a wonder how technical skill, duly employed, ennobles a person’s spirit.”

South Indian typists were to become so ubiquitous across India that when Air India did a cartoon map of the country, Madras was depicted with the image of a south Indian man clicking away at a typewriter. Bobby Kocka, Air India’s legendary commercial director, who in 1946 had devised the Maharajah mascot, told Anvar Alikhan, who passed this anecdote on, that there was such outrage at this stereotyping that Air India had to change the cartoon. But Prakash Tandon, the first Indian to be taken in at management level in Unilever – and later its first Indian chairman – would have confirmed the stereotype; he recalls in his memoirs that when he walked in on his first day: “The clerks were all men: South lndians, if they were stenographers, Christians and Parsis, if they did general work.”

Nissim Ezekiel depicted one in his poem “Occasion”, a rather grim picture of “a South-Indian middle-aged balding man/ without a face or figure/ His name: Ramanathan or Krishnaswamy.” He does typing work for the poet’s friend: “He works all day in a bank/ then comes to me,/ for another hundred rupees a month/Three children, a mother to support,/ invalid wife…”.’ Ezekiel describes the typist’s daily routine: “Half an hour in a queue,/ fifteen minutes in a bus,/ forty minutes in a train,) a long walk from the station to a slum./ Poor fellow, what a life/He ought to be a smuggler/ but doesn’t have the guts.”

Yet for many south Indians, when they took to learning typing, soon after the machines came into the country, the profession seemed more promising. Arnold Wright’s Twentieth Century Impressions of Ceylon: Its History, People, Commerce, Industries, and Resources, a guide published in 1907, records how a Miss Violet Muthukrishna went to Madras to learn stenography and typing and returned to Colombo to open her first commercial typing and training institute in 1901. The profession was clearly established and in demand by then, since Miss Muthukrishna’s institute was an immediate success: “a large number of youths and fair proportion of girls, noting the handsome prospects to be afforded by this line of business, at once light and lucrative, availed themselves of the -opportunity of qualifying as shorthand-typists.”

The early institution of “convent” schools in south India resulted in large numbers of young people looking for such “light and lucrative” work. Since there were more applicants than jobs in government or company offices in the south, the men started travelling north. For the businessmen there, “Madrasi” clerks filled a real need, helping them communicate in English with the British, in the typewritten letters that were soon de rigueur. The fact that these “Madrasis” had little entrepreneurial spirit themselves and were happy to remain with salaried jobs, was something the northern businessmen might have felt contempt for – as in the “doesn’t have the guts” comment of Ezekiel’s narrator – yet could value, since it meant the south Indians could be trusted with company secrets.

This attitude of mixed respect and disdain was, in fact, how northern mercantile communities had always held priests, and since many of those early educated south Indians were Brahmins, they slipped into the same role. They too knew arcane scripts like shorthand, took down oracular statements as dictation and used special tools of trade, with their typewriters as lovingly cleaned and tended as a shrine. Shetty recalled the worshipful way in which the head typist at one company where he worked treated his machine: “He didn’t speak much with people in the office, but he spent a lot of time taking care of his typewriter. Every morning when he came, he would spend the first 10-15 minutes carefully cleaning and taking care of it.” When he retired, Shetty inherited the machine. “It felt very good, actually getting to use such a well-kept machine!” he says.

(To be concluded)

– Vikram Doctor

From: With Great Truth & Regards by Sidharth Bhatia and published by Roli Books for Godrej.