Registered with the Registrar of Newspapers for India under R.N.I 53640/91

Vol. XXVII No. 19, January 16-31, 2018

The City’s Burmese repatriates

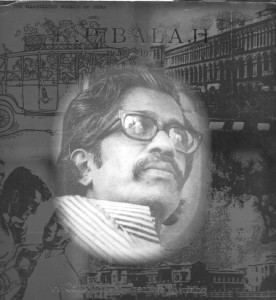

K.P. Balaji (1926-76) died in an air crash in Bombay. From Kathakali in Kerala, he moved to Marg, that cultural journal in Bombay. Joining The Illustrated Weekly of India, he was with it from 1954 to 1961. He then got into advertising with S.H. Benson’s and rose to be one of its Directors. His son, K.P. Karunakaran, settled in Australia, put together a collection of his writings and published them as a commemoration of his father’s 40th death anniversary. Over the next few issues, we publish a few of Balaji’s Madras-focused articles that appeared in The Illustrated Weekly in 1964-65.

K.P. Balaji (1926-76) died in an air crash in Bombay. From Kathakali in Kerala, he moved to Marg, that cultural journal in Bombay. Joining The Illustrated Weekly of India, he was with it from 1954 to 1961. He then got into advertising with S.H. Benson’s and rose to be one of its Directors. His son, K.P. Karunakaran, settled in Australia, put together a collection of his writings and published them as a commemoration of his father’s 40th death anniversary. Over the next few issues, we publish a few of Balaji’s Madras-focused articles that appeared in The Illustrated Weekly in 1964-65.

TODAY’S ARTICLE IS ON REPATRIATES FROM BURMA

Gumidipundi is a wayside station some 25 miles from Madras. For the major part it looks a shabby, straggling village, promoting itself into a suburban dignity with little more than a coat of whitewash on its mud walls. On the station benches, like permanent fixtures, sit a few lethargic coolies. When the train pulls in, they cast a quick, apprising glance at the dozen or so people who get down – and instantly reject them as of no account. I don’t know what this place is known for. One of them who volunteered to be my guide, said sourly, in response to a stock question, “But then I’ve been here only ten years.”

But suddenly, one day, if only momentarily, the picture changed. The people who got down at Gummidipundi (they arrived from the city in special buses) were still of the same plebeian stocks, but they numbered a few hundreds. Most of them were women and children, not noisy or disorderly as you would have expected of a crowd like that, but strangely silent, as the men, too poor to engage coolies, unloaded their meagre possessions – a rusty iron trunk, a basket tight-packed with blackened cooking pots, a clumsy bed-roll tied with rough and knotty coir ropes, etc. The children, some possessively clutching broken toys and battered cardboard boxes, looked around with uncomplaining eyes at what their elders were vaguely referring to as their new home, the “camp” set up by the State Government to receive the first batch of India’s newest dispossessed – the repatriates from Burma.

When I visited the camp a few days later, I found it a scene of much activity, but, significantly, it was mostly woman who were up and about, washing clothes under a common tap or bargaining vehemently with a vegetable vendor. They seemed to have settled down in their new surroundings, with a quick adaptability which is perhaps characteristic of their sex. The men sat in small groups on the verandahs of thatched huts or under trees, full of gossip about their past but with no clear-cut ideas of the future. They appeared to accept things with an equanimity close to despair. The uprooting from their old homes – a slow, coldly calculated political manoeuvre – had given them no moments of heroism, nor had any sudden tragedy sharpened their wits and prepared them for the question, “What next?”

To many of them, India is a strange land. “I don’t know which my home is,” one of them said. “I was born in Burma… There’s no one I can ask now. My parents are both dead. They spoke Tamil. So I presume they came from these parts.”

“How many Indians are coming back? I asked (the official estimate was 2,00,000).

“I don’t know. Maybe five lakhs. Maybe less. Who knows who wants to stay and who wants to leave?”

But, of course, the Indians in Burma have really no choice. The new regime seems to believe that Socialism is a natural corollary to a wholesale export of “aliens”. (The Chinese, according to reports, do not belong to this category.) Indian establishments have been ‘nationalised’. “Even people who have applied for citizenship are being persuaded to leave the country,” one of the repatriates said. “In the past few months, particularly, life was just impossible. Officials used to raid houses and shops and confiscate property. Our wages were cut in half. Some people were sent to jail. They had, we were told, failed to give an accurate account of their assets in Burma.”

It was always the same story: of blatantly unjust, often crude, methods adopted by the Ne Win regime to drive the Indians out of the country. Many had been deprived of their life’s savings and left destitute. The people I saw at Gummidipundi represented the poorest of the poor, who had no money even to buy their passage home, and who, having landed in Madras, did not know where to go.

The refugees recall with gratitude the help they received from the Government of India. In Madras, they told me, they had met, with sympathy and understanding from State officials. They, and thousands of others who were yet to come, pose a staggering problem for the Central and State authorities. Their future is bleak and uncertain – their only hope seems to lie in a programme already initiated, to find them employment in projects and plantations or help them start small-scale industries in different parts of the State.