Registered with the Registrar of Newspapers for India under R.N.I 53640/91

Vol. XXVIII No. 2, May 1-15, 2018

When we exported Iron & Steel to the UK

by Dr. A. Raman araman@csu.edu.au

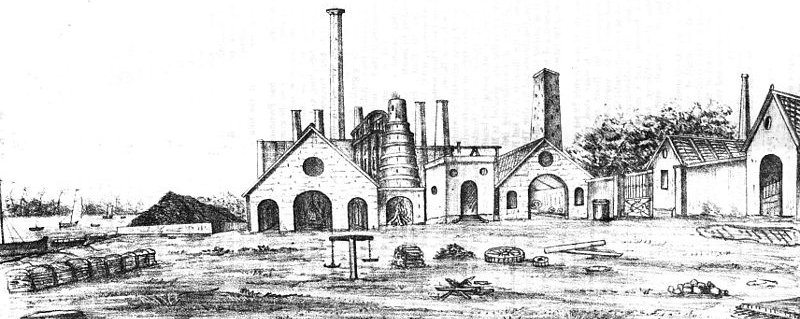

A sketch of the Porto Novo steel works.

Iron production was self-sufficient in 18th Century India and the excess was exported. In the 1800s, many individual ironsmiths operated in the Madras Presidency, producing wrought iron. An association was formed in Madras with the objective of establishing a charcoal-fired iron works in 1830, because the iron ore that occurred naturally in much of the Madras Presidency had/by then been detected. Consequently, an exMadras Civil Servant, Josiah Marshall Heath, ventured to establish a large-scale iron-steel works in Parangipéttai (Porto Novo), 220 km south of Madras, naming it the Porto Novo Iron Works, which went through turbulent phases during its survival.

The remarkable aspect is that the Porto Novo Iron Works was the only large-scale iron and steel factory in the whole of India in the 1830s. Nothing matched with the Porto Novo Iron Works in size and production capacity, which also included the state-of-the-art methods of production of the time. The Porto Novo Iron Works serviced the needs of India and Britain for iron and steel for close to 30 years, although, after 1849, it changed names to Indian Steel & Iron Company and, then, East India Iron Company. In 1887, its prominent 150′ (c.50 m) tall chimney functioned as a beacon for ships sailing along the Porto Novo coast. The indiscriminate exploitation of wood for charcoal and other energy requirements was one sad practice the British Government encouraged to support Heath’s enterprise, which resulted in the loss of precious wood in vast tracts of the Madras Presidency.

Heath, when he was the relieving Commercial Resident of Coimbatore-Nilgiris District, Thomas Munro, the Governor of Madras (1820-1827), instructed him to trial the cultivation of bourbon cotton, then newly introduced from the Americas, in Salem and Coimbatore. Heath resigned his administrative position in 1829 to take up experiments in various scientific efforts towards better technology. He was also an enthusiastic naturalist. He explored southern Indian birds in particular.

Heath’s efforts in making steel in India, in the late 1830s, were blazing new trails towards producing cheaper steel, which he claimed would match in quality with the then best Swedish and Russian steel. His trial of adding 1-3% carburet of manganese as a deoxidiser led to steel production, which cost less by 30-40% in the Sheffield (UK) steel market. This novelty trialled by Heath neither helped him nor his industry, because he failed to patent the procedure.

The following note appeared in the Mining Journal (1857; reproduced in the Sheffield Daily Telegraph, 1857) under ‘Manufacture of Iron and Steel’:

“In 1839 comes the important invention of Josiah Marshall Heath for the manufacture of iron, and which, as regards steel, was as great a stride in the manufacture as compared with any previous process as the process of Uchatius is at the present time. The duration of this patent was, after much litigation, prolonged, by an application to the Privy Council, for seven years. Although the principle of Heath’s invention had been previously described, and even as early as 1799 William Reynolds patented the employment of oxide of manganese or manganese in the conversion of pig iron into malleable iron or steel, but gave no proportions of details, it appears that until the introduction of Heath’s patent no practical results were arrived at.”

Heath applied to the Government at Fort St. George, seeking exclusive rights to build a factory, which he argued would operate on European scientific lines. He further argued that he would be able to supply iron and steel at a much cheaper price than what Britain was getting from Sweden and Russia. Administrators in Madras approved his request declaring that he would enjoy the exclusive rights over the ore material from a vast tract of public land (c. 38,000 sq. mile, 98,500 sq. km). They also in 1825 guaranteed Heath substantial loans and purchase of finished products from his works. They considered it appropriate to grant him a temporary monopoly for 21 years of iron and steel manufacture, thus enabling and encouraging him to persecute this undertaking and to secure a fair and reasonable remuneration for the risk, labour and expenditure.

The following from an article in Indian Engineering is relevant in this context:

“Mr. Heath was a man of great scientific knowledge, and failed to see the advantage of manufacturing Swedish iron and steel. He applied to the Directors of the Honorable E.I. Company, who seeing the benefit to the country of such manufacture, granted to Mr Heath the exclusive privilege of manufacturing iron, by the European process, in the districts of S. and N. Arcot, Trichinopoly, Salem, Coimbatore and Malabar. They granted him the right of cutting in the jungles all the fuel required for the production of iron and also a grant in aid of 9000 pounds, showing the interest they were taking in the industry.”

Before Heath became the full Commercial Resident of Coimbatore-Nilgiris District, he was the relieving Commercial Resident in Salem, which naturally includes a rich dose of iron ore. In this role Heath learnt more about the highly endowed geomorphology of the Salem landscape.

The movement of iron ore from Salem to Porto Novo for Heath’s company was via the sea, especially using the Khan Sahib Brackish Water Canals, which linked the north-lying Véllãr and the south-lying Kollidam (a tributary of the Kaveri). The Khan Sahib Canals were made navigable in 1854 by integrating three locks, one of which debouched into Véllãr, close to which the Porto Novo Iron Works existed. Before this sea-route facility came about, Heath had dug a short canal from Véllãr to the backwaters adjoining the embouchure of the Kollidam, through which Heath moved iron ore in parisal (basket boats, small, circular ferries).

A contemporary description of the layout of Heath’s iron works and the yard reads:

“In front of the blast furnaces, along with a platform ran the pigs bed and the foundry hall…. The foundry was 100’x60′ (30.48 x 18.29m) in size and had proper cranes, air furnaces, cupolas, and other foundry appliances, and was terminated by drying stoves, with their tracks and railway. … The forge consisted of several sheds – The first containing the refinery and afterwards the puddling and reheating furnaces. Another adjoining the helve. A third shed contained the rolling mill, driven by an engine of 50 horsepower. The mill was provided with several sets of rollers of round, square, and flat iron bars, bending gear, rolling plates, saws and shears.”

This facility included two blast furnaces when the factory started (1830?). Two more were added later (date not available). The boilers occurred close to the engine and the flues were communicated via a 150′ (C. 50 m) tall chimney.

Smelting operations during the early days were a disaster. The first hiccup was deciding on the shape of the hearth for a charcoal-fired furnace suiting the chemical nature of the ore and the charcoal used as the energy source. Secondly, the workers brought from Britain were unfamiliar with charcoal-fired furnaces. Conversion of the cast into wrought iron was the next hiccup the British workers and engineers grappled with, although they solved that problem by following the then prevalent methods in France and Germany, using finery fires. Soon, the Porto Novo Iron Works managed to produce good-quality iron and steel and could sell produce to the Government (whether in Madras or in Britain, not clear) for use in their arsenals. The weakness, however, was that they could never achieve and guarantee consistent quality.

(To be concluded)