Registered with the Registrar of Newspapers for India under R.N.I 53640/91

Vol. XXVIII No. 6, July 1-15, 2018

Lost Landmarks of Chennai

SRIRAM V

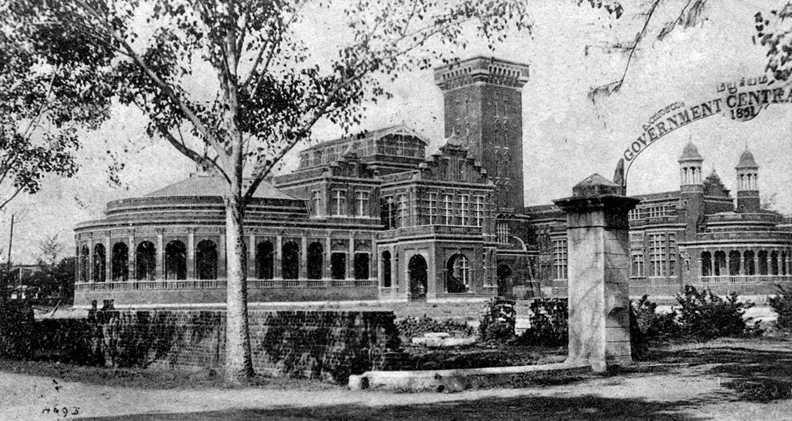

The tower that vanished

Today there is no sign of a tower at the Government Museum, Egmore. Yet, in its time the absence of such a structure would have been completely out of character for the architects who designed the public buildings of Madras. Chisholm, Irwin, Pogson, Brassington – almost all of them believed in their structures being surmounted by a tower. The Museum too was no exception. It is just that the tower does not exist any more. Its disappearance had as much to do with professional rivalry as it had to do with structural problems.

Today there is no sign of a tower at the Government Museum, Egmore. Yet, in its time the absence of such a structure would have been completely out of character for the architects who designed the public buildings of Madras. Chisholm, Irwin, Pogson, Brassington – almost all of them believed in their structures being surmounted by a tower. The Museum too was no exception. It is just that the tower does not exist any more. Its disappearance had as much to do with professional rivalry as it had to do with structural problems.

The Madras Museum, as is well known, emerged from an informal collection of artefacts that people kept adding to at the Madras Literary Society. The latter, founded in 1818, was an adjunct to the College of Fort St. George and lived much of the first century of its existence at old College House, now part of the Directorate of Public Instruction campus, College Road, Egmore. The collection kept growing and was soon allotted the first floor of College House. By the 1850s, Dr. Edward Green Balfour, who was then Superintendent of the Museum, began asking for a suitable premises for the collection. This was granted, with The Pantheon, formerly the principal entertainment space for the British in Madras, being made over to him. The move was completed in 1854.

Thereafter, the Museum grew, with structures such as the Reading Room being added to it by Robert Fellowes Chisholm. But it was in the late 1890s that major expansions took place, with the addition of what were called the Front Buildings, the Theatre and the Public Library being sanctioned. These were all designed by Henry Irwin, then the Consulting Architect to the Government of Madras. Topping the Museum in his design was a tower, 200 ft high and, when completed, the highest in the city.

Its construction was not without drama, apparently, for Edgar Thurston, who was then the Superintendent of the Museum, noted in his Omens and Superstitions of Southern India that the labourers involved believed that evil spirits had to be propitiated. A goat was sacrificed before the “big blocks of granite were placed in position.” Earlier in the century, the foundation stone for the new set of buildings had been laid by Lord Connemara. The work was completed in time for Sir Arthur Havelock to inaugurate them in 1896. The entire stretch was known as the Connemara Victoria Public Library & Museum Section.

Considering that the tower barely stood for a year after inauguration it is quite amazing that there is a written record of how it looked. In his The Tourist’s India, (published by Swann Sonnenschein, 1907), Eustace Alfred Reynolds Ball wrote that Irwin had been inspired by the tower at the Palazzo Vecchio in Florence in his design. Several decades later, Jan Morris was not so impressed when she reviewed the design. The tower was undoubtedly phallic, she declared. But by then the structure was long gone.

Let us now see what led to its untimely demise. Henry Irwin who was the designer had come to Madras in 1888, to succeed Chisholm. He arrived in a blaze of glory, having virtually transformed Simla into an Imperial summer capital, complete with a Viceregal Lodge. In Madras his most magnificent creation was the High Court, designed largely by him and executed mainly by J.H. Stephen, Chief Engineer, PWD, Madras. The same was the case with the Connemara Library and the rest of the Museum. In fact, Irwin had retired in 1896 to Mount Abu, leaving Stephen to see the Museum project through to completion. By the time the new buildings were complete, a new Consulting Architect had arrived in Madras. This was G.S.T. Harris. And he was not so well disposed towards Irwin. His views were also perhaps coloured by the fact that Irwin’s Town Hall in Simla was proving to be a structural nightmare (it would be dismantled 20 years later).

Such fears were not entirely unknown in colonial India. Years earlier, Thomas Fiott de Havilland had to fight the widespread opinion that the dome of St. Andrew’s Kirk in Egmore would come crashing down on the faithful. In 1881, Major Charles Mant went insane and committed suicide over fears that the tower he was building as part of the Laxmi Vilas Palace in Baroda would collapse. This pessimistic view was not shared by R.F. Chisholm, his successor at the task, and he went on to complete it. It is still standing tall. But then not everyone had Chisholm’s breezy confidence.

Thus when Harris began spreading his stories that the Museum Tower was structurally unsound and could collapse any moment, he found ready listeners. There were opponents, of course, in particular the Calcutta-based publication, Indian Engineering, edited by Patrick Doyle. Closer home, J.H. Stephen did his best to defend the tower. But it was a lost cause in the face of consistent propaganda by Harris who also managed to convince Sir Arthur Havelock that the Museum was probably better off without a tower. That swung matters in his favour.

Without losing any further time, Harris gave instructions for the soil around the tower to be opened. That straightaway weakened it. Some of the granite blocks went out of plumb and from then on it was but a matter of time before an army of workers, probably the same team that had built the tower, descended on the spot to demolish it. The Museum was closed for a few weeks, beginning in March 1897, to facilitate the removal. The Indian Engineering lamented that it had been the leading feature of the structure, without which “a magnificent pile of building had been defaced and deformed.” In the event, this appears to have been an isolated cry. The tower is completely forgotten, and indeed, few would even believe that such a structure once existed.

Comments