Registered with the Registrar of Newspapers for India under R.N.I 53640/91

Vol. XXX No. 5 June 16-30, 2020

Lost Landmarks of Chennai

When Madras sent out migrant labour

The first wards

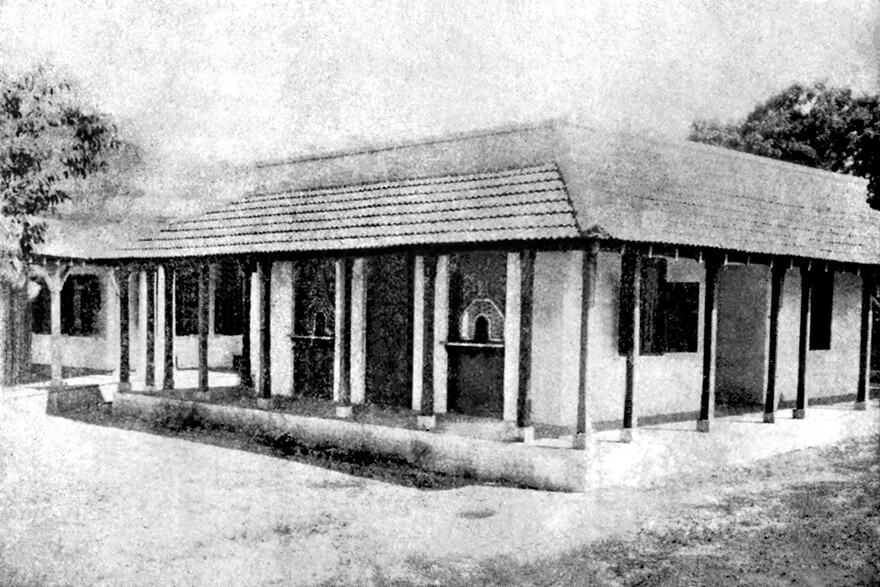

The first wardsof the Isolation Hospital.

The Communicable Diseases Hospital, Tondiarpet.

The Communicable Diseases Hospital, Tondiarpet.The COVID crisis has brought to the fore the problem of migrant labour. States are closing down borders and one Chief Minister has even gone to the extent of stating that if in future other States need labour from his State they need to take permission from his Government! This is all empty talk of course, for there can be no stopping an Indian citizen from moving anywhere within the country in search of employment. As long as there is demand, people will remain on the move. The failure lies not in migration but in not ensuring even basic comforts for these people.

But the happenings do bring to mind an era that spanned the late 19th and early 20th Centuries, when the colonial power actively pursued the export of Indian labour. And Madras was one of the prime centres for this. The British business houses of Madras and their counterparts in other port cities, saw this as a major profiteering opportunity. Some of the most respectable names – Binny and Parry among them – were involved in this trade. And the going was good, while it lasted.

This was of course not slave trade – the kind that Elihu Yale encouraged in 17th Century Madras. That and others of its type elsewhere died out with the abolition of slavery in the 1860s. But the drying up of slave labour resulted in demand for other kinds of labour to manage plantations in the far-flung parts of the empire – Ceylon, the Federated Malay States, South Africa and Fiji to name a few places. In fact, sending out of indentured labour had begun even in the 1840s. And where else but India to recruit from, for after all the country had surplus population even then. With slavery being a strict no-no, such people were euphemistically described as those who migrated out of their free will.

They personally entered into agreements that guaranteed transport to the place of work, wages and tenure. It most significantly omitted all mention of conditions of return and therefore eventually created entire colonies of migrants in most of these countries, leading to lasting social and political trouble.

The process of recruitment was highly formalised – an agent went about collecting the prospects who were all brought to emigration depots from when on they became subjects of the Indian Protector of Emigrants. Here they were inspected medically and made to wait for the ships that would take them to their respective destinations. In Madras, the emigration depot was located at Tondiarpet. The first structure came up in the 1840s and was rebuilt in the 1850s. It was divided into sections, based on country – Mauritius, Fiji, Natal, Malaya, etc. There was a cooling off period before the labour embarked from here. This was to enable family members to come and claim back those who had run away from home! Described as more of a stockade than a building, it was, so several inspection committees claimed, airy and well-ventilated though it is a moot point if any of the inspectors would have cared to live in any of these spaces. Another set of regular visitors comprised missionaries – these were fertile grounds for conversion.

While the administration of the migrants and their eventual transportation was the responsibility of the Government, it depended on a whole host of support services provided by the British companies of Madras. They were involved in almost every aspect, from recruitment, for which they had agents, to sending the labour out, for they held agencies for various transnational shipping lines.

The first we hear of mercantile interest in this labour business dates to the 1850s when the redoubtable Henry Nelson of Parry & Co asked the Government as to why, when migrant ships were allowed to transport 450 people from Calcutta and 500 or 600 from Bombay, Madras shipped them out in relative luxury with only 350 people to a ship. The French, he argued, gave only 60 cubic feet per emigrant, and so why was the local Government giving Madras labour 72 cubic feet? The Government snubbed him saying it had no intention of abandoning the health of its subjects.

We next see the formation of an East Indian Emigration Society whose mission was to promote the emigration of Anglo Indians to Australia. In 1852, fifty Anglo Indian males were ‘exported’ but there was no follow-up action thereafter and the Society collapsed. But the shipping out of migrant labour went on relentlessly to the other countries, the famine of 1875-1877 contributing large numbers. Beginning from 1866, many began to be sent to Transvaal and Natal and by the 1880s, British Guiana became an attractive prospect. But by the 1890s, matters began to sour – the locals in Natal did not want any more Indian labour and a ship from Madras in 1893 was forcibly turned back. The Madras Chamber of Commerce was goaded into action by the powerful mercantile establishments of Madras. This body wrote letters to its counterparts in Johannesburg, Durban and Cape Town, protesting the treatment of “Indians of education and good character in the Transvaal.” The reply was not favourable. But for once, the British business interests of Madras and Mr. M.K. Gandhi in South Africa were of the same view – Indians had had a raw deal.

By then the condition of the emigrants had begun to draw public attention. Song books in Madras city portrayed their miserable existence and longing for home. The song Theyilai Thottathile for instance became a staple in Carnatic music concerts and in plays, and there was not a dry eye in the audience when this was sung. The original, by Subramania Bharathi, was Karumbu Thottathile and portrayed the condition of labour in Fiji. By 1917, the British Government decided to drop emigration as a scheme. The business establishments had already seen this coming and so had over a decade earlier begun to service labour wanting to return to Madras! They thus made money both ways. The Emigration Depots now became places where the incoming people were quarantined and just as in the case of Coronavirus where Royapuram remains a hotspot, this became the place from which plague spread into the city in 1904. Some export of labour continued for a decade or so more, with Fiji becoming the new destination. But with the coming of the World War, this too was given up.

What is interesting is that the plight of the emigrant labour did not die down as a topic of social interest. Attention in particular shifted to Ceylon where manpower was still being sent over, the kanganis or agents being very active down south. Nagapattinam and Rameswaram became the new points of embarkation. Films such as Pati Bhakti and Sati Leelavati, of the 1930s, portrayed heroes leaving for the tea plantations of Ceylon upon facing destitution in India.

The Madras Emigration Depots had however lost their importance by then. With so much of land being occupied by them, the question arose as to what could be done with the space. The Corporation of Madras took it over in 1924, to set up a facility where it could treat those affected with infectious diseases. Cases were compulsorily removed to the Isolation Hospital for Infectious Diseases at Tondiarpet on Tiruvottiyur High Road, for effective isolation and free treatment. Two ambulances were available at the hospital. Any member of the public could requisition their services free of cost at any time of day or night to take cases of infectious diseases to the Hospital. Authority was vested with the Health Officer to take measures for the prevention of an outbreak in the city of any infectious disease. Renamed the Infectious Diseases Hospital in the 1940s, it was to play a pioneering role in the eradication of small pox. Today, it is known as the Communicable Diseases Hospital.

In this time of a pandemic, when the problems of migrant labour dominate the situation, it is interesting to note that our city once traded in migrant labour and that a hospital to treat infectious diseases stands where they were once shipped out from.