Registered with the Registrar of Newspapers for India under R.N.I 53640/91

Vol. XXX No. 5 June 16-30, 2020

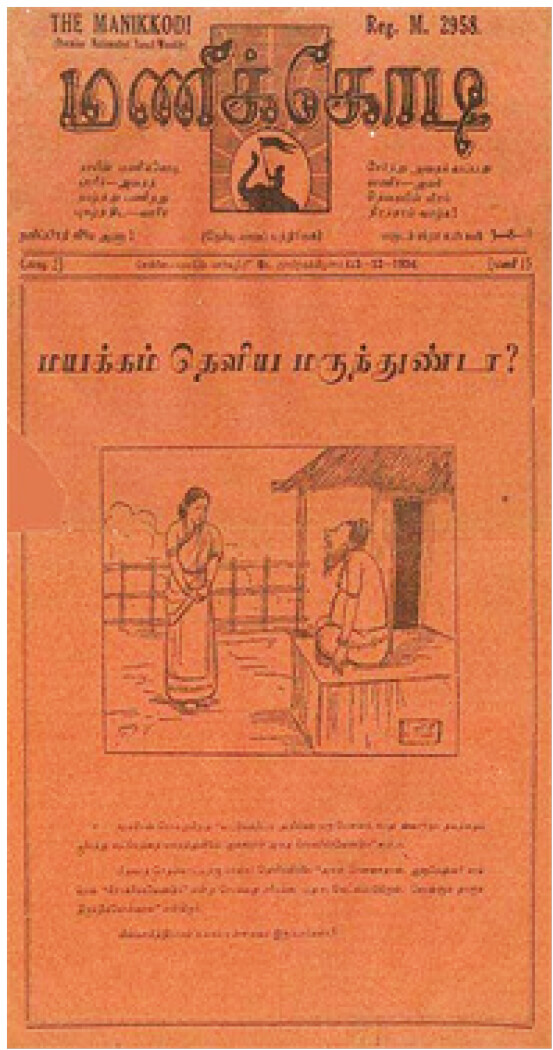

When Manikkodi was Hoisted in Tamil Journalism

by K.R.A. Narasiah

Early Tamil literary periods are divided as Sangam Era, epoch of the Epics (300-600 CE) and Bhakti Era. The last provided major contributions by the Vaishnavite and Saivite saints, the Nayanmars and Azhwars, with religious poetry in excellent Tamil. Later, different styles and forms have been used in the advancement of language with no particular division.

When printing was introduced during colonial times, a distinct quantum jump occurred and there was a sudden spurt of Tamil journals, starting with religious tracts by the Christian missionaries mainly for proselytization.

Soon popular Tamil journals started showing up, mostly following English journals and books but with a touch of nationalism. However, as B.S. Ramaiah, an early Tamil prolific writer said, the next definitive period of Tamil was that of Manikkodi.

When popular journals showed up, the most successful among them was Ananda Vikatan, which catered to the taste of a large section of Tamil reading upper and middle class. Originally started by Boodur Vaidyanatha Iyer in 1928, it was taken over by S.S. Vasan and with Kalki Krishnamurthy joining it as editor, it became very popular.

Humour and non-serious fiction in the journal proved extremely popular and other journals tried to emulate Ananda Vikatan. But there was no specific literary contribution to the language of Tamil in writing.

V. Kalyanasundaram, known popularly as Thiru Vi. Ka., first introduced a new simple style of literary Tamil in the nationalist daily Desa Bhaktan during 1917-20. Till then, literary Tamil was handled by Tamil pundits who made it impossible for ordinary people to understand the written language. It was followed by Tamil Nadu, yet another nationalist journal started by one Varadarajulu Naidu. The revolutionary writer V. Ramaswami Iyengar (1899-1951) or simply Va. Raa. as he was known, noted, “If pundits meet, the Tamil spoken is unintelligible to the common man; if English-educated Tamils meet it is the same story. It is to Varadarajulu Naidu that credit and honour goes for smashing this restrictive mischief.” Va. Raa. had abandoned his college education in Tiruchi and his attempts to join the National College of Calcutta did not fructify. He then went to Puducherry where he spent considerable time in the company of Subramanya Bharati. It was there that he met many nationalist leaders like Aurobindo Ghose, Neelakanta Brahmachari, Surendra Nath Arya and V.V.S. Iyer.

When he returned to Madras, he met ‘Andhra Kesari’ T. Prakasam, who was running a nationalist magazine Swarajya, whose English edition was taken care of by K. Srinivasan, an exemplary journalist. On Prakasam’s request, Va. Raa., took charge of the Tamil edition.

A graduate of the Madras University, K. Srinivasan (1899-1975) had wide experience in English journalism as a correspondent for the Sunday Observer of London during the 1920s. He was groomed by S. Sadanand, the founder of the Free Press of India, the first nationalist news agency, and the Free Press Journal. Srinivasan started planning a Tamil journal with a high level of literary content and nationalist fervour in understandable Tamil. Va.Raa., an admirer of Subramanya Bharati, was by then known for his zeal in writing about social reform with a touch of fine humour. He, along with another nationalist, T. S. Chockalingam (1899-1966), joined Srinivasan (incidentally known as Stalin Srinivasan as he sported a Stalin-like moustache). The trio began planning a new journal in Tamil.

According to my uncle PG ‘Chitti’ Sundararajan, all the three of them were sitting in the sands opposite the Fort St. George discussing about the journal and debating a name for it. Just then they saw the fluttering Union Jack on the Fort’s mast and thought of Subramanya Bharati, who sang about the flag of India in his famous song Thaayin Manikkodi. The sun was setting and the Union Jack was being lowered and one of them remarked how nice it would be if Thaayin Manikkodi was hoisted there. All the three at once decided that the new journal would be named Manikkodi. It was in this dramatic manner that the name was conceived.

They founded the first avant garde Tamil weekly in 1933 with Va. Raa. as its editor. The first issue was published on September 17th 1933, coinciding with Bharati’s 12th death anniversary. In the beginning, the office was located at 35, Sembudoss Street, George Town and subsequently moved to 7, Naniyappa Naicken Street in the same locality. In the style of the newspapers then, Manikkodi was also published in the same size and priced at one anna.

When it was launched, it was hailed by many journals including the Ananda Vikatan. It appears that Kalki Krishnamurthy came to the office of Manikkodi to congratulate Va. Raa. The Hindu carried it as an item of news, giving prominence to the effort in one of its September 1933 issues. (Incidentally, The Hindu in its issue dated 18th September 1983, under its popular rubric Fifty Years Ago, repeated the news item on Manikkodi, underlining its importance).

Va. Raa. was now looking out for thinking individuals who could contribute to the journal and be encouraged to write for it. Chitti Sundararajan, who later became a regular contributor to Manikkodi says that it was due to a friend that he chanced upon Manikkodi. This friend, S. S. Krishnamurthy, was the editor of a Tamil daily India and was writing editorials for Swadesamithran. He showed Chitti an issue of Manikkodi and told him that it was creating a stir in the literary world and that Chitti should write for it. By then, Chitti was an established English writer as well as the editor of Marina, and was a bit critical about Tamil writing; he wondered if there was such a thing as a literary world in Tamil. But when he read an article by Va. Raa., Chitti was so struck by its style and language that he wanted to contribute to Manikkodi. In Chitti’s words, “I was awed by the simple but powerful message it carried and was a little worried if my article would be accepted but emboldened by the friend’s enthusiastic words, I did send a piece to the journal”. In his usual humorous vein, Chitti said, “It could have been the force of circumstance, or perhaps a testing time for Manikkodi – for I had decided to write for it.”

For the subject of the article he took Gandhi’s visit to Madras, and recounted it in a humorous way. He did receive a reply from Manikkodi inviting him to visit the office. Chitti thought probably the editor wanted to advise him not to write! When he did visit the office, he found Srinivasan welcoming him. Even then Chitti thought that he was going to give some soothing words before returning the article. Va. Raa. was lying on a towel spread on the floor! Srinivasan offered Chitti a seat and Va. Raa., getting up and seating himself on the towel, began to speak to him. Chitti was stunned as Va. Raa. spoke to him for nearly an hour. “He spoke in a majestic tone resembling a waterfall and his laughter with a metallic sound simply overpowered me. His speech was filled with new ideas flashing through it. I was mesmerized by him,” said Chitti.

Srinivasan handed Chitti the fresh and then current issue of Manikkodi. And Chitti couldn’t believe his eyes when he found his article carried in it. Chitti with his usual humour remarked, “From that day English escaped from me and testing times began for Tamil.”

(To be continued next fortnight)