Registered with the Registrar of Newspapers for India under R.N.I 53640/91

Vol. XXXI No. 2, May 1-15, 2021

John Shortt and his works on Indian cattle

by Ramya Raman, Chitra Narayanasamy, and Anantanarayanan Raman

Cover page of Manual of Indian Cattle and Sheep (1889).

John Shortt (1822–1889) of the Madras Medical Service also practiced as a veterinary surgeon in Madras after qualifying as a Member of the Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons of England. Based on his veterinary practice in Madras Presidency, he wrote an invaluable book A Manual of Indian Cattle and Sheep – Their Breeds, Management and Diseases, the third and last edition of which was published in Madras, soon after his death in Yercaud (Salem). Besides talking of the etiology and management of cattle and sheep diseases, Shortt also extensively writes of the phenotypic variations among cattle and sheep in southern India in particular. This article validates Shortt’s notes and the historical significance of this monumental work by referring to the biological diversity of southern Indian cattle in the light of modern cattle research.

John Shortt born February 26, 1822, started as an ‘apothecary’ after training at the Madras Medical School (Madras Medical College from 1850) in January 1846. He travelled in 1850 to Scotland to earn an M.D. (Medicinae Doctore) and M.R.C.S. (Member of the Royal College of Surgeons of London) titles. He also qualified for M.R.C.V.S. (Member of the Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons). He returned to Madras and joined MMS as an Assistant Surgeon in July 1854. He was admitted into M.R.C.P. (Membership of Royal College of Physicians of London) in 1859 and was elevated as Full Surgeon on September 20, 1866. Crawford lists Shortt in Indian Medical Service, but in none of his books does Shortt use ‘I.M.S.’ after his name, although several of his other academic titles figure in his books.

Cover page of monograph on the culture and manufacture of indigo (1862) (left); and (right) page from the same monograph showing two columns of text in English and Urdu.

He was the Superintendent of Vaccination in Madras, held fellowships of the Linnean Society of London and the Zoological Society. He was the Corresponding Fellow of the Société d’Anthropologie (Paris) and Berliner Gesellschaft für Anthropologie, Ethnologie, und Urgeschichte. As an elected member of the Obstetrical Society of London, he was the Secretary of the Madras Chapter of the Obstetrical Society of London. He retired as Deputy Surgeon-General of Madras, holding the rank of Lieutenant-Colonel, when Edward Green Balfour was the Surgeon-General. Unverifiable notes on Shortt indicate that he held an L.D.Sc. (Licentiate in Dental Science).

Shortt wrote many books and papers. Besides those in medicine and biology, he translated C. Maclean’s Treatise on Smallpox (1857) into Tamil, edited H(enry) R(hodes) Morgan’s Forestry in Southern India (1884), and wrote the Handbook of Coffee Planting in Southern India (1864), An Account of the Tribes of the Neilgherries (1868), The Hill Ranges of Southern India (1871), A Manual of Vaccination for the Pupils of the Vaccination Department, Madras (1874), A Manual of Family Medicine (1875), Snakes of the Several Districts of the Madras Presidency (1875), The Cocoanut Palm or Cocos Nucifera (1888), and the Manual of Indian Agriculture (1889), in addition to a volume on veterinary medicine. His paper, ‘The Armenians of Madras’ in the inaugural issue of Journal of Anthropology (London), is noteworthy. He experimented with cobra venom. He retired on February 12, 1878 and died in Yercaud (Madras Presidency) on 24 April 1889, a little before the third edition of Manual of Indian Cattle and Sheep — their Breeds, Management and Diseases appeared.

The range of titles he has written on – from human and veterinary medicine to anthropology and natural history – is amazing. These pieces reveal his acumen and capacity to deal with varied subjects with authority. His monograph on the culture and manufacture of indigo (1862) includes a parallel text in Urdu (Hindoostani), speaking volumes of his versatility in Indian languages. He impresses as a polymath. John Shortt was the earliest overseas-qualified Indian medical doctor and a veterinary surgeon in India.

* * *

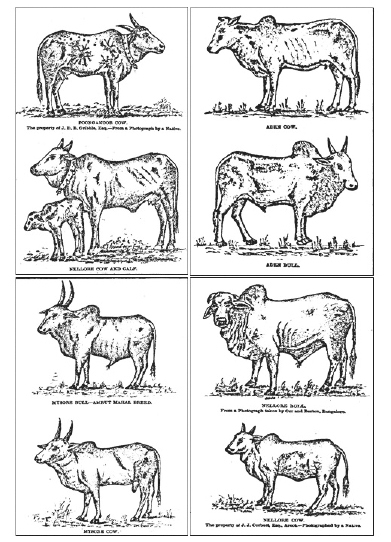

Phenotypic variations of selected breeds among southern Indian Bos indicus from Shortt (1889).

Shortt’s Manual of Indian Cattle (1889) states in the preface that he had been practising veterinary medicine and surgery for more than 30 years and whatever information was included in the book relied on his veterinary practice. The section concerned with indigenous breeds is the outcome of another task, which he explains:

‘To the Board of Revenue I have to tender my best thanks for their courteous permission to make use of an Essay on the “Indigenous Breeds of Cattle,” for which a prize of one hundred rupees was awarded to me at the Agricultural Show of 1874 at Sydapetta (Saidapet).’

This 179-page book is divided into three sections, the first dealing with cattle, the second with buffalo, and the third with sheep. The section on cattle consists of (i) cattle (pp. 1–61) and (ii) cattle diseases (pp. 63–106). Details on indigenous breeds occur in the subsection ‘cattle’. The section on buffalo runs from p. 107 to p. 114. The one on sheep consists of (i) sheep (pp. 115–129), (ii) sheep diseases (pp. 129–151), followed by a 7-page section on goats. Pages 153–179 include several appendices referring to multiple details of veterinary importance. His remarks essentially refer to the cattle of the Madras Presidency, which included parts of Andhra Pradesh, Kerala, and Karnataka of modern India, although the justification for the title ‘Indian cattle’ is reasonably met by occasional references to cattle breeds of other parts of India.

His references to cattle in what is now Tamil Nadu include the following:

Shortt refers to Indian cattle breeds by the regions they are confined to, such as ‘Mysore’, ‘Nellore’, ‘North’ and ‘South Arcot’, ‘Tanjore’, ‘Trichinopoly’, ‘Salem’, and ‘Coimbatore’. He refers briefly to the exotic ‘Aden cattle’ as well. The section on Mysore cattle is extensive. According to Shortt (pp. 2–3): “These draught cattle are celebrated for their power of endurance, active and quick in their paces, somewhat restive, and fiery in disposition.”

A Mysore bullock is 12–15 hands (= 120–150 cm) tall with a compact carcass, straight and long horns. Horns are 2–3 feet long (a 3-feet long horn is hard to imagine).

Animals are gray (light–dark gray) and occasionally white. Shortt comments on the temperament of this breed: “It is generally a high-spirited animal, and requires kind and conciliating treatment to break in.”

His remark (p. 3) is worthy of note: “Almost all other cattle seen in the country are importations or crosses between the above-mentioned breeds.”

The sturdiness and stamina of the Mysore cattle (in high probability, the Hallikars) are best indicated in D. Davidson’s report (Bombay Column of the English Army in Afghanistan) made sometime in the 1850s (Gunn, 1909):

“No draught cattle was sufficient as the 230 Mysore bullocks which accompanied the Bombay troops to Afghanistan. It was entirely from this very superior cattle that no part of the Bombay Park was required to be abandoned when the troops were returning to India over the almost impracticable road through the Tobab mountains. These cattle were frequently upwards of 16 hours in yoke. The draught bullocks with the Bengal Army were the property of the government, but were not, in my opinion, as fine animals as the Mysore bullocks.”

(To be continued next fortnight)