Registered with the Registrar of Newspapers for India under R.N.I 53640/91

Vol. XXXIII No. 18, January 1-15, 2024

Kalidas – Part III

-- by S. Muthuvel, muthuvelsa@gmail.com

In those days, there were many remarks that Kalidas contained ‘patriotic songs and keerthanas that had little to do with the film’s story.’ However, the truth is that along with the tale of the titular Kalidas, the film also contained two other segments which were short features in their own right. We have seen earlier that the story of Kalidas appeared in the second segment in the film. In this article, we will examine the clues left behind about the third segment, the kurathi dance.

The Kurathi Dance

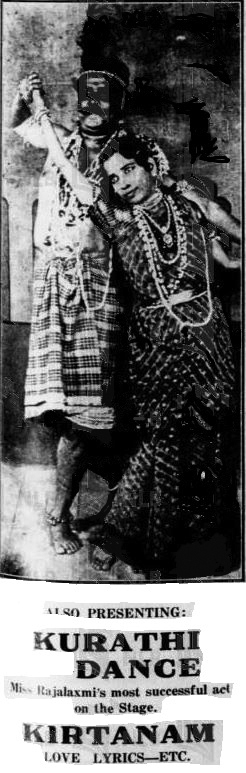

A still from T.P. Rajalakshmi’s kurathi dance.

A still from T.P. Rajalakshmi’s kurathi dance.Per observations made by Theodore Baskaran, the 1931 feature Kurathi Paatum Dansum was the first Tamil talkie ever produced. This, in fact, is the short feature Kurathi Dance that was screened as part of the film Kalidas. As a matter of fact, this talkie was produced before Kalidas, but it is unclear whether it was screened to public audiences before the film’s release. If it had been screened, it would have clinched the honour of being the first Tamil talkie. Since the first recorded appearance of the feature is as part of Kalidas, the latter won the honour instead.

The reviews and advertisements of Kalidas that appeared in the magazine Swadesamitran make mention of the kurathi dance:

The film also contains a kurathi dance performed by Ms. Jhansi Bai and Mr. RD. It is a must-watch for audiences.

There are many documented passages and photographs available of the North Indian actresses of that period who acted in silent films. However, there is no information about Jhansi Bai. The same goes for Mr. RD, too.

Who were Jhansi Bai and RD?

An unclear but rare still of a scene from Kalidas. Courtesy: The Hindu archives.

An unclear but rare still of a scene from Kalidas. Courtesy: The Hindu archives.A never-before-seen 1931 advertisement for Kalidas has been procured by the writer of this column. The ad was found in a foreign daily, filling about half a page of its contents. Misapprehensions about potential copyright issues prevent him from sharing details about the daily or a copy of the ad; he is able to share only the information it contains. But the advertisement is an important piece of evidence since it was a contemporary of the times that Kalidas was screened in. It also carries stills from the kurathi dance that have not been seen for the past 92 years and have made way for a few well-supported assessments.

The still from the kurathi dance that was carried in the Kalidas advertisement makes it patently clear that the dancer seen alongside the kuravan is T.P. Rajalakshmi – in other words, Jhansi Bai is none other than T.P. Rajalakshmi! The figure and features seen in the image enable the identification.

The first attempt to produce a Tamil talkie was undertaken by the Bombay-based Sagar Movietone company in 1931. As a result, the four-reel short-film Kurathi Paatum Dansum performed by the woman artiste Jhansi Bai was produced for the first time ever in Tamil.

Thus wrote Theodore Baskaran in his book Em Thamizhar Seitha Padam. His observations are based on irrefutable proof. Thus it was that in the past, doubts lingered about this person called Jhansi Bai. The book Message Bearers, also by Theodore Baskaran, helps put the matter to rest – in it, there is a reference that T.P. Rajalakshmi acted in a short film called Kurathi Paatum Dansum produced by Sagar Movietone. Then there is T.P. Rajalakshmi’s remarks in a later interview, where she said, “I performed a kurathi dance in the multi-feature Kalidas.’ All these evidences taken together confirm that Rajalakshmi and Jhansi Bai are one and the same person.

The name Rajalakshmi was already famous in those days in stage dramas and silent films. It is entirely possible that Jhansi Bai had been adopted as trendy screen name for cinema. It is this writer’s assessment that the 4-reel long Kurathi Paatum Dansum produced by Sagar Movietone was later shortened to 2 reels and screened as a part of Kalidas. The kurathi dance shown in both features are the same. Though the director of the piece is unknown, it is a fact that Ardeshir Irani had business interests in both Sagar Movietone and Imperial Company. According to the writer’s estimate, this is the reason why this short feature was shown as part of the Imperial Company’s Kalidas.

S.M. Hadi.

S.M. Hadi.There is also a reference that the person who danced with Jhansi Bai was RD. Who was RD? No information can be procured about anyone of that name. But, there was an actor called Hadi in those days. This Hadi – S. Mohammad Hadi, to be precise – was a supporting actor and his name keeps coming up in references to early Hindi talkies. It makes one wonder whether it was him in fact that Swadesamitran referred to when they said RD. After all, we have already seen a few examples of the mistakes that appeared in the advertisements carried in Swadesamitran. The author believes that the men seen in both the images presented here – one, a still from the kurathi dance in Kalidas and the other, a still of S.M. Hadi – are the same person. The likeness of features is unmistakeable. So Swadesamitran had to have meant him when they referred to RD. Kalki’s remark that the kuravan in the kurathi dance had a paunch also matches with the assessment.

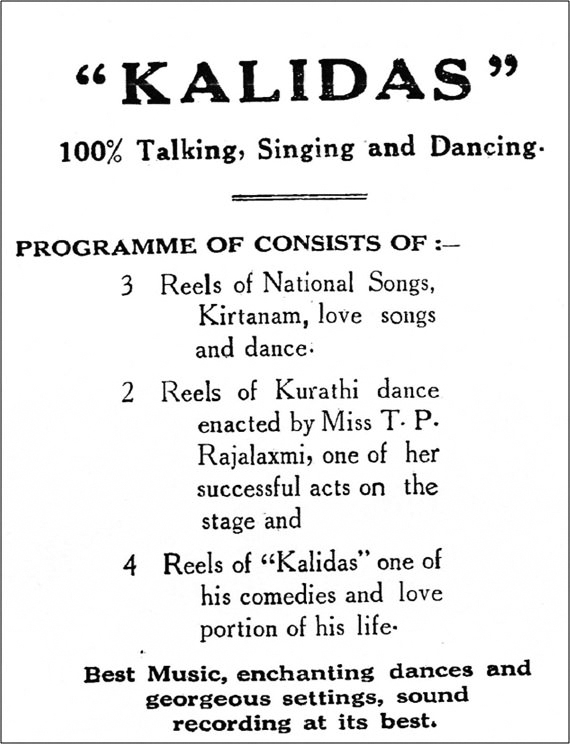

A page from the Kalidas songbook.

A page from the Kalidas songbook.We will now turn to fresh information that has emerged from the English daily. It carries an entry dated 16.12.1931, which says that Kalidas was ‘brought directly from Chennai.’ When Chennai’s Kinema Central theatre released the film for Deepavali celebrations on 31.10.1931, it was announced that it would run for only one week; did Kalidas perhaps have more screenings beyond that? How many copies of the film were made? These questions remain unanswered.

The number of seats that Kinema Central had in those days were about 650, and there were about two to three screenings a day. It should be kept in mind that until 1928, the films with long run times at Kinema Central averaged about two weeks of screenings. Even after talkies appeared on the screen, run-times ranging to a couple of weeks were notable achievements. Raja Harischandra was released in Kinema Central theatre in April 1932 and clocked a run time of 4 weeks, according to available documentation – that was a remarkable triumph of the times.

Unlike silent films, talkies were adapted to local audiences. So it is possible that Kalidas was screened only in places where Tamil and Telugu were widely spoken. Also, it must be remembered that theatres with the facility to showcase audio were available only in big cities like the metros, and even these were scant in number.

In Chennai, it was at the Elphinstone theatre on 13.4.1929 that the facility for audio was established for the very first time. It was around this time that the facility became available in Colombo, too – this is confirmed by T.V. Ramnath, the editor of the magazine Pesum Padam. In Coimbatore, the establishment of Samikannu Vincent’s Kovai Variety Hall was wired for sound for the first time on 14.4.1930; that Kalidas was screened in Coimbatore is also confirmed by Gundoosi Gopal as an evergreen memory.

As for travellling cinema tents, only a few were wired for sound in those days, and there is no information whether Kalidas was screened through these. With such available information at hand, one can imagine how many people of those days got to see Kalidas.

There is also evidence that Kalidas was released in Malay countries. It must have been released in Rangoon – now Myanmar – too.

A 12-page booklet containing stills from the film and all the songs was distributed for free. It was also provided at no charge to clubs and associations in India and Ceylon.

That 12-page booklet referred to above is most probably the songbook that we talk about today. The cover page of the Kalidas songbook carries a printed mention of the Kinema Central release along with the date. Inside, there is an advertisement for a Chennai clothing shop, which fills about two and a half pages. This was rather unusual for songbooks. Kalidas’ songbook appears to have been an arrangement to not only promote the film but also carry advertisements for investing parties. Also, since this was the first film songbook in a South Indian language, it was quite unlike its predecessors from the drama, gramophone and cinema herald backgrounds.

Today, Kalidas is lost and the people who saw the film are no longer around. Only the available documentation helps us learn more about the film. If further evidence emerges in the form of published or audio data from the film, this topic can be explored further. In fact, there are chances to get such evidence from other countries where Kalidas was released as well. The English archives of The Hindu carry advertisements not only for Kalidas but also for other films that followed. Those who are interested in the subject and who can access the archives of The Madras Mail, Madras Times, The Hindu and Ananda Vikatan can explore the documents.

A key reason behind the sharing of the author’s research process and findings is to learn from the approaches and conclusions of fellow cinephiles. Readers are thus welcome to write to him and share their opinions and thoughts about this article.

We saw that there was much hesitation in dubbing Kalidas as the first Tamil talkie. This begs the question – which film, then, was called the first Tamil talkie without any hesitation whatsoever? Nearly everyone until now says the honour goes to Galavarishi. But the film that followed Kalidas was Raja Harischandra. We shall, in the next segment, explore documentation relating to this film.