Registered with the Registrar of Newspapers for India under R.N.I 53640/91

Vol. XXXIII No. 2, May 1-15, 2023

Randor Guy – remembering a social historian

-- by Sriram V

In the passing of Randor Guy, the city of Madras that is Chennai has lost a social historian who kept alive memories of an era long gone. Today heritage may be back in fashion but at a time in the 1970s, 80s and 90s when much of it was forgotten, it was a few such as Randor who kept bringing it back into focus. He in particular specialised in the story of people – famous personalities of the city and through them showcased legal, criminal and cinema histories.

Born Madabushi Rangadorai in 1934 into an orthodox Iyengar family that had roots in Nellore but in later years spread to Kanchipuram and Madras, Randor had the misfortune to lose his mother and brother when very young and that left a lasting impact on him. His father M. Varahaswami Iyengar was a prominent lawyer who later gave up practice.

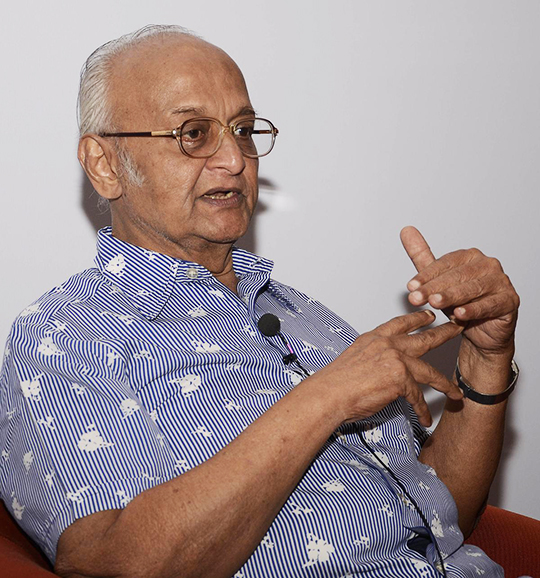

Randor Guy. Picture courtesy: The Hindu.

Randor Guy. Picture courtesy: The Hindu.In keeping with family tradition, Rangadorai qualified in law and apprenticed under the famed legal luminary V.C. Gopalratnam. He later moved onto stockbroking and then advertising before finding his metier in writing about the past. This was when he took on a pen name, which was a clever anagram of his real one and emerged as Randor Guy.

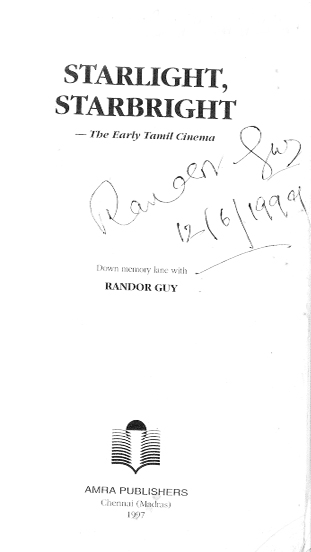

Author’s copy of Starlight, Starbright with Randor’s signature.

Author’s copy of Starlight, Starbright with Randor’s signature.Over the years Randor emerged as an engaging chronicler of personalities of Chennai. Coming as he did from a family of lawyers it was perhaps natural that he developed a penchant for writing on the prominent lawyers of the city, in particular the luminaries that lived in Palathope (he always wrote of the place as Pelathope), the four Mada Streets of Mylapore, and along Luz Church Road. Even by the 1980s what he described seemed a wondrous world and by the new Millenium it all seemed fables – houses of 150 grounds, incomes for cases amounting to six figures in the early 1900s and entire appeals sent by telegrams. But incredible as it may all have seemed, all of it was true and meticulously researched. He was not a person to indulge in adulation and he generally made sure his pen portraits were balanced – to quote him he kicked sacred bulls and described heroes with all their flaws, warts and all.

Randor was also deeply interested and well informed on Madras cinema – Tamil and Telugu. Here again he made people his focus – actors, actresses, technicians, directors and producers. He painstakingly documented several lives. Not many would be aware that he was also an encyclopaedia of Hollywood history. Yet another facet of Randor’s was his fascination with crime. He documented many famous cases of Madras, narrating them in a sensational style, sometimes giving dramatic twists to the stories for readability, not always based on fact. But they did make for gripping reading.

Given all of this, he was soon a writer in demand and his output was prodigious. Starlight Starbright, perhaps his finest work, was a personality-based study of Tamil cinema of the 1930s and 1940s. This was brought out by Amra Publishers in 1997. By the 1990s, a serialised column he wrote for Dinamani titled Anraiya Chennai Pramukhargal became popular – it carried the life sketches of 83 personalities of the city. Manivasagar Pathippagam brought it out in two volumes in 2002. He wrote a crime puzzle series for one of the city’s newspapers, though opinions vary as to which one it was – The Mail or Indian Express. He wrote novels of suspense in Tamil. And he wrote scripts for Jag Mundra, a maker of films in the erotic genre in Hollywood. In the 1990s, Randor wrote a column in Aside, and later articles for Madras Musings. He wrote an entire series for Mylapore Times based on his favourite subject – the luminaries of that area. Anna Nagar Times too carried his stories. The Hindu featured his Blast from the Past, which was a series on famous Tamil and Telugu movies – the info culled from the hundreds of film song books in his possession, buttressed by his own long years of research. More books came out during this time. Crime Writer’s Case Book (2007, KK Books) compiled his articles on famous Madras crimes. These had originally appeared in Tamil in the Kumudam magazine. There are some who aver that Randor’s published books number more than fifty but I am not able to recall any other than the above. He also wrote a book on the Madras Seva Sadan, commissioned by the Trust that runs this body.

I first met Randor in 1999, when he gave a talk at the Sir C.P. Ramaswami Aiyar Foundation, on Legal Luminaries of Madras. The hall was packed and the heat terrible but Randor kept the audience spellbound and in splits. At the end of it, I got his autograph on Starlight Starbright and introduced myself. We became good friends. When Sanjay Subrahmanyan and I ran the website Sangeetham.com, we commissioned Randor to do a series for it on Carnatic Musicians in Tamil Cinema. With photos supplied by Film News Anandan, the column was a success. He knew his Carnatic music – lyrics, ragas and all, though he never let on this aspect. When I wrote Carnatic Summer, and the Devadasi and the Saint, he was one of my valuable resources. During the course of the research. Randor and I would have long phone conversations. I also had the opportunity to visit him at his Ayanavaram residence and be introduced to his wife Dola, and daughters Maria and Priya. It was also through him that I got introduced to yet another treasure trove of information – V.A.K. Ranga Rao. They were very close friends.

R.T. Chari, noted patron of the arts was one of Randor’s admirers and in fact it was he who sponsored the publication of Starlight Starbright. When Chari embarked on his monthly South India Heritage Series of Lectures in 2002, Randor was naturally a speaker of choice. Not only did he inaugurate the series which would go on for almost 18 years but he also was a fixture at the programmes, dropping off only when mobility became an issue for him in his later years. Chari later sponsored yet another compilation of Randor’s writings titled Memories of Madras, Its Movies, Musicians, and Men of Letters.

Randor always peppered his speeches with the observation that there was more to be said, which he would do so over a drink. He was true to his word and was the life and soul of parties that he attended, regaling the group that would rapidly form around him with another variety of tales of the city’s past. But there was never any malice. Randor was himself a true representative of what he described often – a gracious world, long past.

The passing of elder daughter Maria around ten years ago marked the beginning of Randor’s long decline. He was not quite the same person there after. Mobility issues became severe and that prevented him from frequenting the social and cultural venues he was fond of and familiar with. The onset of the Covid pandemic only made matters worse. In the last year of his life, Randor had the satisfaction of much of his archival material being acquired by the National Film Archive of India. He and his wife moved into a hospice where he was well looked after. The end came on Sunday, April 23, 2023.

As Randor always signed off his email – it was Hasta la Vista to a gifted writer and raconteur of the past.

* * *

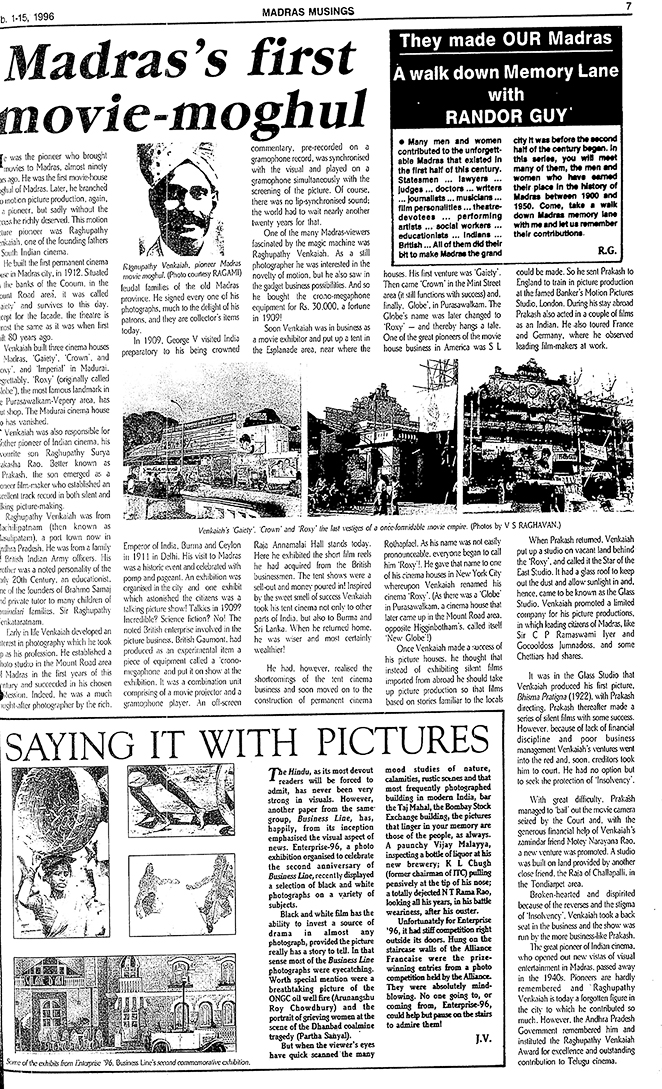

As a tribute to Randor Guy, we reproduce here an article written by him, for a series in Madras Musings “They made OUR Madras” – A walk down Memory Lane with Randor Guy – which focussed on men and women who had earned their place in the history of Madras between 1900 and 1950. This article appeared in the February 1-15, 1996 issue of Madras Musings. –The Editor

Madras’s first movie-moghul

He was the pioneer who brought movies to Madras, almost ninety years ago. He was the first movie-house moghul of Madras. Later, he branched into motion picture production, again, a pioneer, but sadly without the sucess he richly deserved. This motion picture pioneer was Raghupathy Venkaiah, one of the founding fathers of South Indian cinema.

He built the first permanent cinema house in Madras city, in 1912. Situated the banks of the Cooum, in the Mount Road area, it was called Gaiety and survives to this day. Except for the façade, the theatre is almost the same as it was when first built 80 years ago.

Venkaiah built three cinema houses in Madras, ‘Gaiety’, ‘Crown’, and ‘Roxy’, and ‘Imperial’ in Madurai. Regrettably, ‘Roxy’ (originally called ‘Globe’), the most famous landmark in the Purasawalkam-Vepery area, has shut shop. The Madurai cinema house has also vanished. (The Crown and Gaiety also no longer exists now – The Editor.)

Venkaiah was also responsible for another pioneer of Indian cinema, his favourite son Raghupathy Surya Prakasha Rao. Better known as Prakash. the son emerged as a pioneer film-maker who established an excellent track record in both silent and talking picture-making.

Raghupathy Venkaiah was from Machulipatnam (then known as Masulipatam), a port town now in Andhra Pradesh. He was from a family of British Indian Army officers. His father was a noted personality of the early 20th Century, an educationist, one of the founders of Brahmo Samaj and private tutor to many children of Zamindari families, Sir Raghupathy Venkataratnam.

Early in life Venkaiah developed an interest in photography, which he took up as his profession. He established a photo studio in the Mount Road area of Madras in the first years of this century and succeeded in his chosen profession. Indeed, he was a much sought-after photographer by the rich, feudal families of the old Madras province. He signed every one of his photographs, much to the delight of his patrons, and they are collector’s items today.

In 1909, George V visited India preparatory to his being crowned Emperor of India, Burma and Ceylon in 1911 in Delhi. His visit to Madras was a historic event and celebrated with pomp and pageant. An exhibition was organised in the city and one exhibit which astonished the citizens was a talking picture show! Talkies in 1909? Incredible? Science fiction? No! The noted British enterprise involved in the picture business. British Gaumont, had produced as an experimental item a piece of equipment called a crono-megaphone and put it on show at the exhibition. It was a combination unit comprising of a movie projector and a gramophone player. An off-screen commentary, pre-recorded on a gramophone record, was synchronised with the visual and played on a gramophone simultaneously with the screening of the picture. Of course, there was no lip-synchronised sound; the world had to wait nearly another twenty years for that.

One of the many Madras-viewers fascinated by the magic machine was Raghupathy Venkaiah. As a still photographer he was interested in the novelty of motion, but he also saw in the gadget business possibilities. And so he bought the crono-megaphone equipment for Rs. 30,000, a fortune in 1909!

Soon Venkaiah was in business as a movie exhibitor and put up a tent in the Esplanade area, near where the Raja Annamalai Hall stands today. Here he exhibited the short film reels he had acquired from the British businessmen. The tent shows were a sell-out and money poured in! Inspired by the sweet smell of success Venkaiah took his tent cinema not only to other parts of India but also to Burma and Sri Lanka. When he returned home, he was wiser and most certainly wealthier!

He had however, realised the shortcomings of the tent cinema business and soon moved on to the construction of permanent cinema houses. His first venture was ‘Gaiety’. Then came ‘Crown’ in the Mint Street area (it still functions with success) and, finally, ‘Globe’, in Purasawalkam. The Globe’s name was later changed to ‘Roxy’ – and thereby hangs a tale. One of the great pioneers of the movie house business in America was S.L. Rothapfael. As his name was not easily pronounceable everyone began to call him ‘Roxy’! He gave that name to one of his cinema houses in New York City whereupon Venkaiah renamed his cinema ‘Roxy’. (As there was a ‘Globe’ in Purasawalkam, a cinema house that later came up in the Mount Road area, opposite Higginbotham’s, called itself ‘New Globe’!)

Once Venkaiah made a success of his picture houses, he thought that instead of exhibiting silent films imported from abroad he should take up picture production so that films based on stories familiar to the locals could be made. So he sent Prakash to England to train in picture production at the famed Banker’s Motion Pictures Studio, London. During his stay abroad Prakash also acted in a couple of films as an Indian. He also toured France and Germany, where he observed leading film-makers at work.

When Prakash returned, Venkaiah put up a studio on vacant land behind the ‘Roxy’, and called it the Star of the East Studio. It had a glass roof to keep out the dust and allow sunlight in and, hence, came to be known as the Glass Studio. Venkaiah promoted a limited company for his picture productions, in which leading citizens of Madras, like Sir C.P. Ramaswami lyer and Gocooldoss Jumnadoss. and some Chettiars had shares.

It was in the Glass Studio that Venkaiah produced his first picture, Bhisma Pratigna (1922) with Prakash directing. Prakash thereafter made a series of silent films with some success. However, because of lack of financial discipline and poor business management Venkaiah’s ventures went into the red and soon creditors took him to court. He had no option but to seek the protection of ‘Insolvency’.

With great difficulty, Prakash managed to ‘bail’ out the movie camera seized by the Court and, with the generous financial help of Venkaiah’s zamindar friend Motey Narayana Rao, a new venture was promoted. A studio was built on land provided by another close friend the Raja of Challapalli, in the Tondiarpet area. Broken-hearted and dispirited because of the reverses and the stigma of ‘Insolvency’, Venkaiah took a back seat in the business and the show was run by the more business-like Prakash.

The great pioneer of Indian cinema, who opened out new vistas of visual entertainment in Madras, passed away in the 1940s.